The James Webb Space Telescope peers at some of the most distant galaxies in the universe. Now, it’s looked into ours.

Astronomers turned Webb — the most powerful observatory in space — to a portion of the Milky Way‘s core, capturing extreme ongoings and vigorous star formation in unprecedented detail. Unlike the Hubble telescope, which largely views visible light, Webb views a type of light called infrared. These longer wavelengths penetrate thick clouds of cosmic gas, affording never-before-seen cosmic imagery.

“There’s never been any infrared data on this region with the level of resolution and sensitivity we get with Webb, so we are seeing lots of features here for the first time,” Samuel Crowe, an undergraduate student at the University of Virginia in Charlottesville who led the imaging project, said in a statement. “Webb reveals an incredible amount of detail, allowing us to investigate star formation in this sort of environment in a way that wasn’t possible previously.”

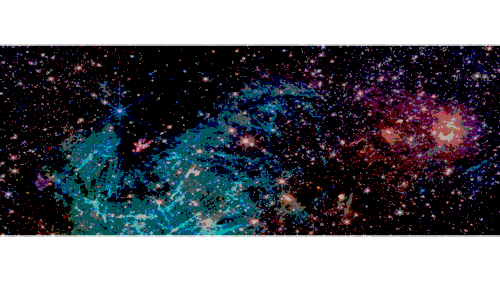

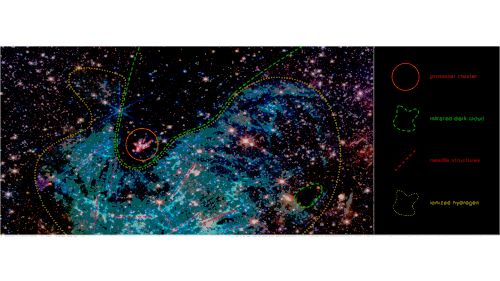

This galactic area is dubbed Sagittarius C (Sgr C), a region that’s home to intense star formation and located some 25,000 light-years beyond Earth, which is relatively close in cosmic terms. For reference, one light-year equals 5.88 trillion miles. Here’s what you’re seeing in the image captured by the Webb telescope’s NIRCam (Near-Infrared Camera) instrument (the second image is labeled).

– Half a million stars: “An estimated 500,000 stars shine in this image of the Sagittarius C (Sgr C) region, along with some as-yet-unidentified features,” NASA explained.

– Cluster of protostars: At the center-left is a bright pink amorphous shape. This is a group of protostars, which are growing stars. “At the heart of this young cluster is a previously known, massive protostar over 30 times the mass of our Sun,” the space agency noted. “The cloud the protostars are emerging from is so dense that the light from stars behind it cannot achieve Webb, making it appear less crowded when in fact it is one of the most densely packed areas of the image.”

– Vast region of chaotic gas: The expansive region (some 25 light-years across) colored cyan is a type of hydrogen gas “containing needle-admire structures that lack any uniform orientation,” NASA said. A future research question is investigating what drove the formation of this vast gaseous cloud.

A star-filled region of space near the core of the Milky Way galaxy.

Credit: NASA / ESA / CSA / STScI / Samuel Crowe (UVA)

Labeled portions of the Webb telescope’s view of the Sagittarius C region of the Milky Way.

Credit: NASA / ESA / CSA / STScI / Samuel Crowe (UVA)

A momentous feature of the Milky Way galaxy’s core is not featured here. At the center of most galaxies lies a supermassive black hole (an object so dense and gravitationally powerful that not even light can escape its comprehend), and at the core of the Milky Way lies Sagittarius A*. It has the mass of some 4 million suns, though black holes can be much, much more massive.

The Webb telescope’s powerful abilities

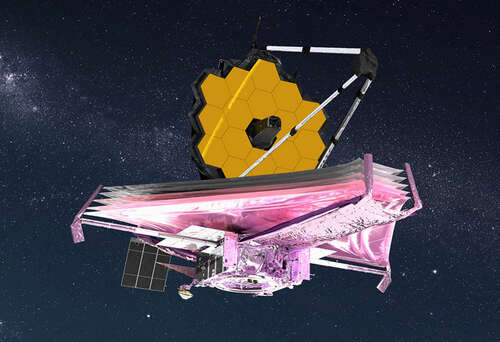

The Webb telescope — a scientific collaboration between NASA, the ESA, and the Canadian Space Agency — is designed to peer into the deepest cosmos and unveil new insights about the early universe. But it’s also peering at intriguing planets in our galaxy, along with the planets and moons in our solar system.

Want more science and tech news delivered straight to your inbox? Sign up for Mashable’s Light Speed newsletter today.

Here’s how Webb is achieving unparalleled feats, and likely will for decades:

– Giant mirror: Webb’s mirror, which captures light, is over 21 feet across. That’s over two and a half times larger than the Hubble Space Telescope’s mirror. Capturing more light allows Webb to see more distant, ancient objects. As described above, the telescope is peering at stars and galaxies that formed over 13 billion years ago, just a few hundred million years after the Big Bang.

“We’re going to see the very first stars and galaxies that ever formed,” Jean Creighton, an astronomer and the director of the Manfred Olson Planetarium at the University of Wisconsin–Milwaukee, told Mashable in 2021.

– Infrared view: Unlike Hubble, which largely views light that’s visible to us, Webb is primarily an infrared telescope, meaning it views light in the infrared spectrum. This allows us to see far more of the universe. Infrared has longer wavelengths than visible light, so the light waves more efficiently slip through cosmic clouds; the light doesn’t as often collide with and get scattered by these densely packed particles. Ultimately, Webb’s infrared eyesight can penetrate places Hubble can’t.

“It lifts the veil,” said Creighton.

– Peering into distant exoplanets: The Webb telescope carries specialized equipment called spectrographs that will revolutionize our understanding of these far-off worlds. The instruments can decipher what molecules (such as water, carbon dioxide, and methane) exist in the atmospheres of distant exoplanets — be they gas giants or smaller rocky worlds. Webb will look at exoplanets in the Milky Way galaxy. Who knows what we’ll find?

“We might learn things we never thought about,” Mercedes López-Morales, an exoplanet researcher and astrophysicist at the Center for Astrophysics-Harvard & Smithsonian, told Mashable in 2021.

Already, astronomers have successfully found intriguing chemical reactions on a planet 700 light-years away, and as described above, the observatory has started looking at one of the most anticipated places in the cosmos: the rocky, Earth-sized planets of the TRAPPIST solar system.

An artist’s conception of the James Webb Space Telescope orbiting the sun 1 million miles from Earth.

Credit: NASA GSFC / CIL / Adriana Manrique Gutierrez