A lot of us now spend much of our work and leisure time peering at the web through a browser—and for that time to be spent as productively as possible, the browser in question needs to run swiftly and smoothly. There’s actually an integrated browser setting to help with this, too: Hardware acceleration.

While the option is in almost every modern web browser, it’s buried quite deep within the settings screens in most cases, so you might never have encountered it. However, on many Windows and macOS systems, it can significantly affect how quickly you can get around the web.

How hardware acceleration works

Hardware acceleration means your browser accelerates its performance by making full use of the hardware available on your computer, Specifically, hardware components beyond the Central Processing Unit (CPU) that form the main brains of your system.

The best example is giving graphically intensive tasks—appreciate playing high-definition video—to the graphics processing unit (GPU), a dedicated card inside your computer, or something integrated into the main chipset. The GPU can do the job better, some CPU time is freed up for other tasks, and laptops should also see some battery life benefits.

It’s not just the GPU, though—your system might have specialized audio or even AI processing units that your browser can use. Your browser won’t know what’s available, but it will inquire the operating system to split up the rendering page workload most efficiently.

You’ll see the biggest gains on the most complex websites, appreciate those hosting games or sophisticated apps. In the same way that your graphics card can help with an intensive video editing or scene rendering task in a desktop application, it can also help with whatever your browser is dealing with.

Now, this all may seem obvious—of course, you want the graphics processor handling graphics—and it is to a certain extent: That’s why hardware acceleration is typically switched on by default. But it’s still a relatively new idea, as our computers have become more powerful, and websites and web apps have become more demanding.

Most of the time, you’ll want to leave hardware acceleration switched on. It can occasionally provoke issues, usually with older or slower computers or older websites, so it can still be turned off to help troubleshoot performance issues and bugs.

How to enable hardware acceleration

How you switch hardware acceleration on or off will depend on the browser you’re using, but the setting shouldn’t be difficult to find. In most cases, you should find that hardware acceleration is already enabled, giving your browser a performance boost.

In Google Chrome, click the three dots to the top right of the browser window, then Settings: Open the System tab to see the Use hardware acceleration when available toggle switch. One cool extra in Chrome is that you can type “chrome://gpu” into the address bar to see how hardware acceleration is used with graphics on your system.

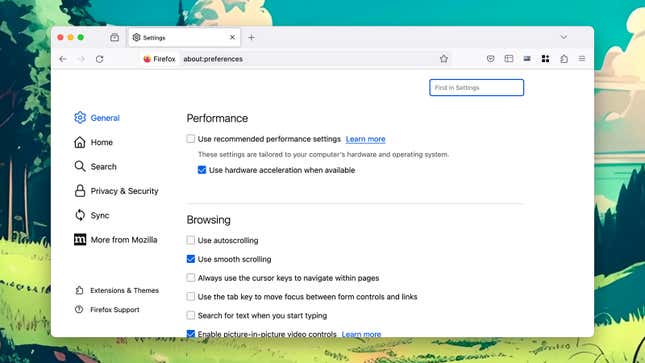

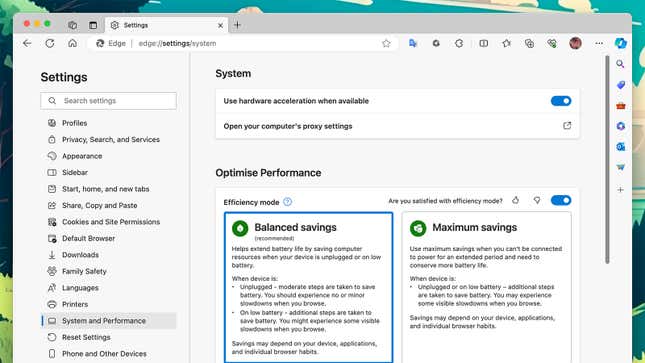

If you’re in Microsoft Edge, click the three dots (top right), then Settings and System and Performance to find the hardware acceleration feature. For those of you using Firefox, click the three horizontal lines (top right), then Settings and General: Under the Performance heading, Use recommended performance settings will be enabled by default, but if you uncheck this, you can turn hardware acceleration on or off.

Apple tends to make more decisions on behalf of its users, and macOS doesn’t have to worry about running on a virtually unlimited number of hardware combinations as Windows does. And for those reasons, there’s no hardware acceleration option in Safari since macOS Catalina is switched on all the time.

As we’ve said, you should only really need to turn hardware acceleration off if you’re noticing buggy browser behavior, and most of the time it should work for you, not against you. There are occasionally issues with specific hardware components and hardware acceleration, but they’re now pretty rare.

For the best results, keep your browser, OS, and graphics drivers up to date—which applies in general anyway. It means every level of the feature will be running on the most up-to-date and modern code.