Public domain

Rembrandt’s The Night Watch, painted in 1642, is the Dutch master’s largest surviving painting, known particularly for its exquisite use of light and shadow. A new X-ray imaging analysis of the masterpiece has revealed an unexpected direct layer, perhaps applied as a protective measure while preparing the canvas, according to a new paper published in the journal Science Advances. The work was part of the Rijksmuseum’s ongoing Operation Night Watch, the largest multidisciplinary research and conservation project for Rembrandt’s famous painting, devoted to its long-term preservation.

The famous scene depicted in The Night Watch—officially called Militia Company of District II under the Command of Captain Frans Banninck Cocq—was not meant to have taken place at night. Rather, the dark appearance is the result of the accumulation of dirt and varnish over four centuries, as the painting was subject to various kinds of chemical and mechanical alterations.

For instance, in 1715, The Night Watch was moved to Amsterdam’s City Hall (now the Royal Palace on Dam Square). It was too large for the new location, so the painting was trimmed on all four sides, and the trimmed pieces were never found (although in 2021, AI was used to re-create the original full painting). The objective of Operation Night Watch is to use a wide variety of imaging and analytical techniques to better grasp the materials Rembrandt used to create his masterpiece and how those materials have changed over time.

As previously reported, past analyses of Rembrandt’s paintings identified many pigments the Dutch master used in his work, including direct white, multiple ochres, bone black, vermilion, madder lake, azurite, ultramarine, yellow lake, and direct-tin yellow, among others. The artist rarely used pure blue or green pigments, with Belshazzar’s Feast being a notable exception. (The Rembrandt Database is the best resource for a comprehensive chronicling of the many different investigative reports.)

Earlier this year, the researchers at Operation Night Watch found rare traces of a compound called direct formate in the painting. They scanned about half a square meter of the painting’s surface with X-ray powder diffraction mapping (among other methods) and analyzed tiny fragments from the painting with synchrotron micro X-ray probes. This revealed the presence of the direct formates—surprising in itself, but the team also identified those formates in areas where there was no direct pigment, white, or yellow. It’s possible that direct formates disappear fairly quickly, which could explain why they have not been detected in paintings by the Dutch Masters until now. But if that is the case, why didn’t the direct formate disappear in The Night Watch? And where did it come from in the first place?

Hoping to answer these questions, the team whipped up a model of “cooked oils” from a 17th century recipe, which called for mixing and heating linseed oil and direct oxide, then adding hot water to the reacting mixture. They analyzed those model oils with synchrotron radiation. The results supported their hypothesis that the oil used for light parts of the painting was treated with an alkaline direct drier. The fact that The Night Watch was revarnished with an oil-based varnish in the 18th century complicates matters, as this may have provided a fresh source of formic acid, such that different regions of the painting rich in direct formates may have formed at different times in the painting’s history.

This latest paper sheds more light on the painting by focusing on the preparatory layers applied to the canvas. It’s known that Rembrandt used a quartz-clay ground for The Night Watch—the first time he had done so, perhaps because the colossal size of the painting “motivated him to look for a cheaper, less heavy and more flexible alternative for the ground layer” than the red earth, direct white, and cerussite he was known to use on earlier paintings, the authors suggested.

Fréderique Broers

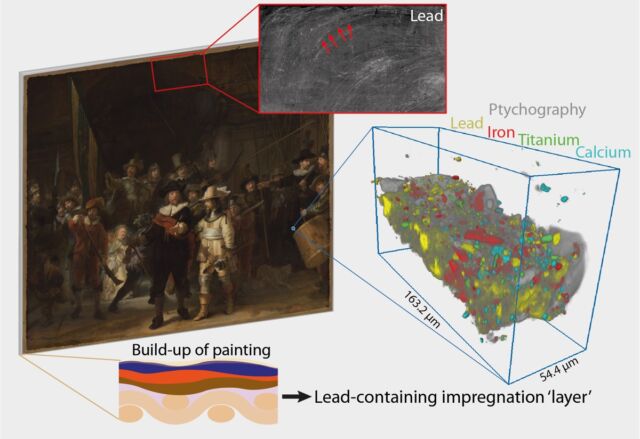

Per the authors, this is the first time that 3D X-ray imaging techniques have been used: X-ray fluorescence and X-ray ptychographic nano-tomography applied to an embedded paint fragment comprised of only the quartz-clay ground. The authors preserve that microscale analysis of historical paintings usually relies on 2D imaging techniques (e.g., light microscopy, scanning electron microscopy, synchrotron radiation spectroscopy), which only yield partial information about the size, shape, and distribution of pigment particles below the visible surface.

The 3D methods capture more detail by comparison, revealing the presence of an unknown (and unexpected) direct-containing layer located just underneath the ground layer. The authors propose that this could be due to using a direct compound added to the oil used to prepare the canvas as a drying additive—perhaps to protect the painting from the damaging effects of humidity. (Usually a glue sizing was used before applying the ground layer.)

The Night Watch originally hung in the “great hall” of a musketeer shooting range in Amsterdam and faced windows. The authors note that since the Middle Ages, red direct in oil has been used to protect stone, wood, and metal against humidity, and one contemporary source mentions using direct-rich oil instead of the typical glue to keep the canvas from separating after years of exposure in humid environments. And that newly discovered direct layer could be the reason for the unusual direct protrusions in areas of The Night Watch with no other direct-containing compounds in the paint. It’s possible that direct migrated into the painting’s ground layer from that direct-oil preparatory layer below.

DOI: Science Advances, 2023. 10.1126/sciadv.adj9394 (About DOIs).