As efficient creators and stewards of wetlands, beavers provide a hospitable ecosystem for dozens of other creatures, from insects, frogs, and turtles to owls, otters, great blue herons, and even moose and deer. What’s more, by harvesting undergrowth for their dams and creating ponds and bogs that raise the moisture content of the soil, beavers lessen the likelihood that forest fires will spread. As forest fires devastated Oregon in 2021, beaver wetlands remained green and lush, acting as natural firebreaks. On aerial images of the charred landscape, the beaver’s habitat stands out, a wide and verdant ribbon running through the blackened trees.

While not all property owners who live near beaver habitats appreciate the animals’ tree removal services, the pro-beaver movement seems to be getting more organized. In November 2023, some 300 beaver restoration advocates from North America and Europe gathered in the Beaver State (Oregon) for the annual State of the Beaver conference. “Seventy-five percent of the artificial wetland restoration projects done in America over the past 30 years have failed,” conference cofounder Stanley Petrowski told the Daily Yonder. “But when beavers do it, they do it perfectly.”

BeaverCon, held near Baltimore in June of 2022, and the Midwest Beaver Summit, held in Chicago and online in September 2023, attracted similar crowds of humans interested in promoting beaver welfare.

It is, in fact, possible to find ways to allow beavers to continue creating their watery habitats in ways that minimize damage to human infrastructure. For example, devices such as the Beaver Deceiver can be installed to prevent beavers from damming culverts, which often leads to flooding of roads. Skip Lisle, founder of Beaver Deceivers International of Grafton, Vermont, first developed the device in the 1990s to beaver-proof the Penobscot Nation’s 130 miles of roads in Maine. “In all likelihood, they are the first large landowner to completely beaver-proof their property nonlethally,” he says.

Living organic chemical factory

At the base of their tail, all beavers have two castor sacs that store castoreum, a complex, granular substance with a strong and long-lasting musky smell. It is made up of at least 24 different compounds, primarily derived from the barks of the various trees in the beaver’s diet. Beavers deposit castoreum atop foot-high mounds of mud, sticks, and grass to mark the edges of their territory.

Humans have long valued castoreum. About 400 BCE, Hippocrates, a chronicler of natural cures, wrote of its wonderful medical properties. Around 77 CE, the Roman naturalist Pliny listed castoreum as a cure for headaches, constipation, and epilepsy. In the Middle Ages the list of maladies castoreum was said to cure expanded to include dysentery, worms, fleas, pleurisy, gout, rheumatism, insomnia, hysteria, memory loss, and liver problems.

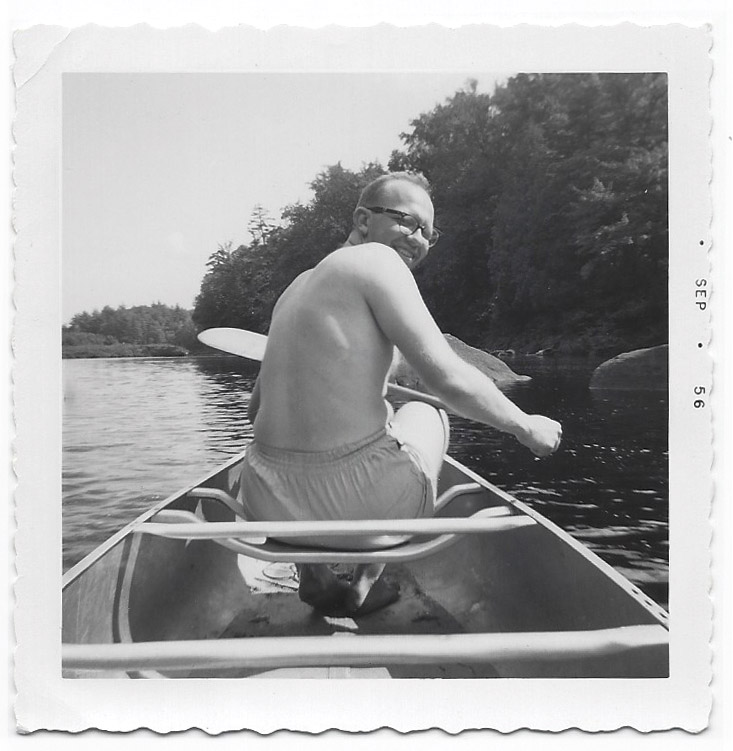

COURTESY OF WILLIAM MILLER

As it turns out, quite a few of the tree barks that beavers prefer contain compounds with known medicinal benefits. Phenols, for example, are often anti-inflammatory and antiseptic and can have antiviral properties. They include salicylic acid (a precursor to aspirin), which can be found in the bark of willow, poplar, and alder trees—all beaver favorites. The beaver’s system functions as a natural pharmacy, extracting these compounds (among others) and secreting them in the form of castoreum.

Humans have also used castoreum for several nonmedical applications, such as in high-end “leather note” perfumes including Shalimar, Givenchy III, and Chanel’s Antaeus. It is an ingredient in some bourbons and vodkas and has been used in Sweden to flavor “Bäverhojt” (literally, beaver shout) schnapps.

Today, most castoreum is harvested in a sterile environment by anesthetizing beavers and expressing the castor sacs near their tails. As a food additive, castoreum extract is “generally recognized as safe,” according to the FDA. But at close to $100 per pound, it’s used sparingly. The total annual US consumption of dried castoreum is around 300 pounds.