A team of academic researchers show that a new set of attacks called ‘VoltSchemer’ can inject voice commands to manipulate a smartphone’s voice assistant through the magnetic field emitted by an off-the-shelf wireless charger.

VoltSchemer can also be used to cause physical damage to the mobile device and to heat items close to the charger to a temperature above 536F (280C).

A technical paper signed by researchers at the University of Florida and CertiK describes VoltSchemer as an attack that leverages electromagnetic interference to manipulate the charger’s behavior.

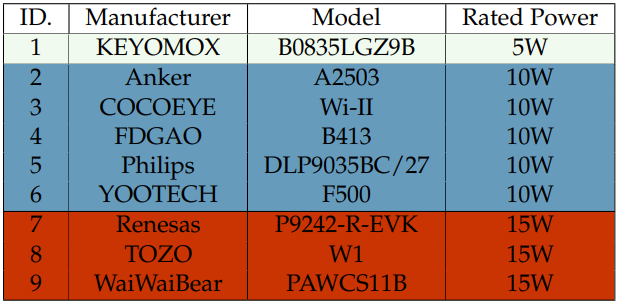

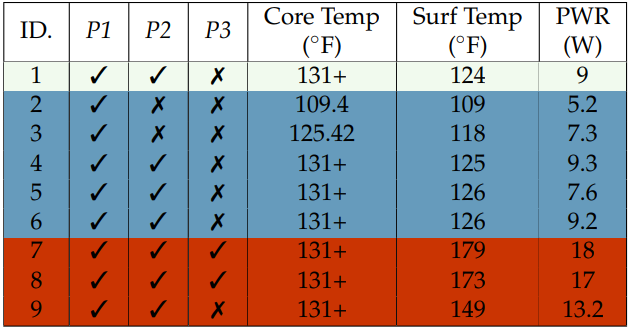

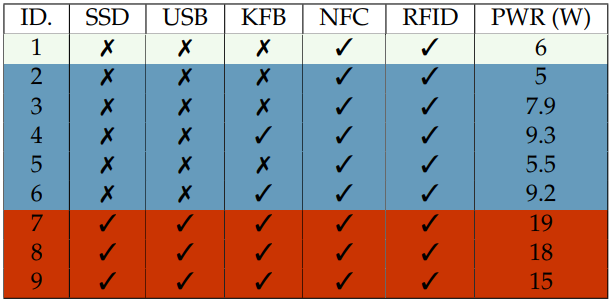

To demonstrate the attack, the researchers carried out tests on nine top-selling wireless chargers available worldwide, highlighting gaps in the security of these products.

What makes these attacks possible

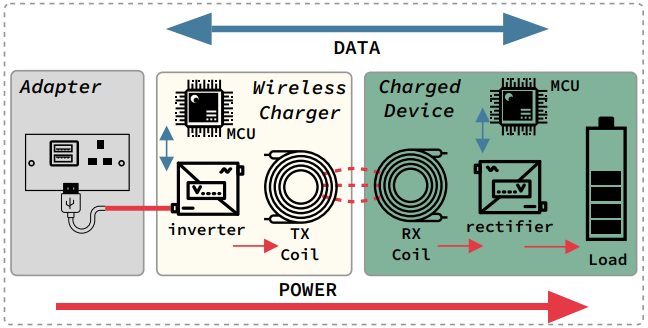

Wireless charging systems typically use electromagnetic fields to transfer energy between two objects, relying on the principle of electromagnetic induction.

The charging station contains a transmitter coil, where alternating current flows through to create an oscillating magnetic field, and the smartphone contains a receiver coil that captures the energy from the magnetic field and converts it to electrical energy to charge the battery.

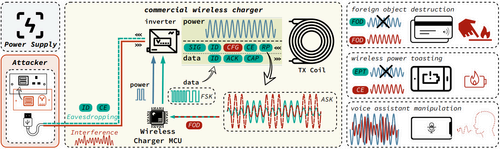

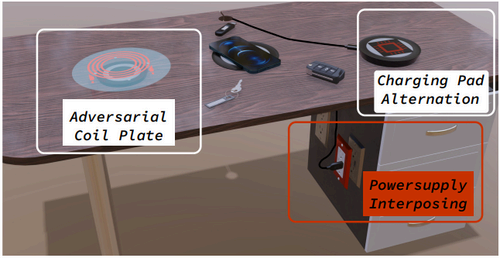

Attackers can manipulate the voltage supplied on a charger’s input and finely tune the voltage fluctuations (noise) to create an interference signal that can alter the characteristics of the generated magnetic fields.

Voltage manipulation can be introduced by an interposing device, requiring no physical modification of the charging station or software infection of the smartphone device.

The researchers say that this noise signal can interfere with the regular data exchange between the charging station and the smartphone, both of which use microcontrollers that manage the charging process, to distort the power signal and corrupt the transmitted data with high precision.

In essence, VoltSchemer takes advantage of security flaws in the hardware design of wireless charging systems and the protocols governing their communication.

This opens up the way to at least three potential attack vectors for the VoltSchemer attacks, including overheating/overcharging, bypassing Qi safety standards, and injecting voice commands on the charging smartphone.

Tricking voice assistants and frying phones

Smartphones are designed to stop charging once the battery is full to prevent overcharging, which is communicated with the charging station to reduce or cut off power delivery.

The noise signal introduced by VoltSchemer can interfere with this communication, keeping the power delivery to its maximum and causing the smartphone on the charging pad to overcharge and overheat, introducing a significant safety hazard.

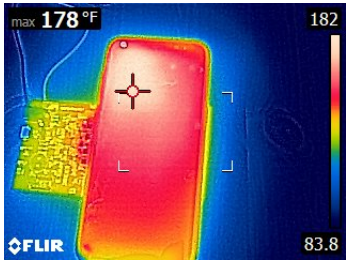

The researchers describe their experiments using a Samsung Galaxy S8 device as follows:

Upon injecting CE packets to increase power, the temperature rapidly rose. Shortly after, the phone tried to halt power transfer by transmitting EPT packets due to overheating, but the voltage interference introduced by our voltage manipulator corrupted these, making the charger unresponsive.

Misled by false CE and RP packets, the charger kept transferring power, further raising the temperature. The phone further activated more protective measures: closing apps and, limiting user interaction at 126 F◦ and initiating emergency shutdown at 170 F (76.7 C). Still, power transfer continued, maintaining a dangerously high temperature, stabilizing at 178 F (81 C).

(arxiv.org)

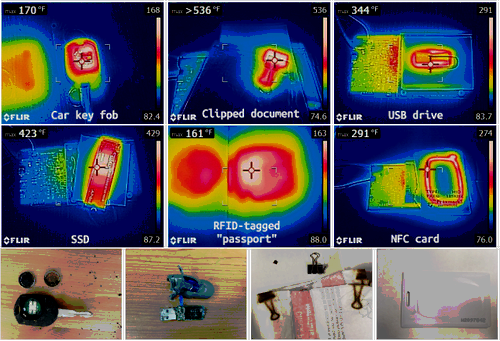

The second VoltSchemer attack type can bypass the Qi-standard safety mechanisms to initiate energy transfer to nearby non-supported items. Some examples could include car key fobs, USB sticks, RFID or NFC chips used in payment cards and access control, SSD drives in laptops, and other items in close proximity of the charging pad.

By experimenting with paper clips holding documents, the researchers managed to heat them to 536 F (280 C), which is more than enough to set the papers on fire.

Electronic items are not designed to support this level of heat and could get damaged in such a VoltSchemer attack.

In the case of a car key fob, the attack caused the battery to blow up and destroy the device. With USB storage drives, the voltage transfer led to data loss, just like in the case of SSD drives.

A third type of attack the researchers tested was to deliver inaudible voice commands to assistants on iOS (Siri) and Android (Google Assistant).

The researchers have demonstrated that it is possible to inject a series of voice commands through noise signals transmitted over the charging station’s range, achieving call initiation, browsing a website, or launching an app.

However, this attack comes with limitations that could make it impractical in a real-life scenario. An attacker would first have to record the target’s activation commands and then add to the power adapter’s output voice signals. which have the most important information in a frequency band below 10kHz.

“[…]when a voice signal is added to the power adapter’s output voltage, it can modulate the power signal at the TX coil with limited attenuation and distortions,” the researchers explain, adding that a recent study showed that through magnetic couplings, “an AM-modulated magnetic field can cause magnetic-induced sound (MIS) in the microphone circuits of modern smartphones.”

The interposing devices introducing the malicious voltage fluctuations could be anything disguised as a legitimate accessory, distributed through various means like promotional giveaways, second-hand sales, or as replacements for supposedly recalled products.

While delivering higher voltage to mobile device on the charging pad or nearby items using a wireless charger is a feasible scenario, manipulating phone assistants using VoltSchemer does set a higher barrier in terms of the attacker’s skills and motivation.

These discoveries highlight security gaps in modern charging stations and standards, and call for better designs that are more resilient to electromagnetic interference.

The researchers disclosed their findings to the vendors of the tested charging stations and discussed countermeasures that could remove the risk of a VoltSchemer attack.