Despite technology seeping into practically every corner of our lives, computer-related education in Washington is woefully limited.

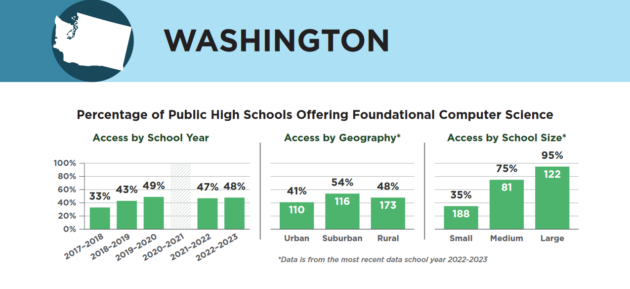

Last year, 8.4% of the Washington’s high school students attending either public or state-tribal schools took a computer science class, according to state data. That’s fewer than 31,000 teens. Roughly half of the public or state-tribal schools even offer a computer science class.

“It’s like a watercooler for people who are passionate about these things.”

– Ben Shapiro, associate professor in the Allen School

But fixing the situation won’t be easy. There aren’t enough computer science teachers. There aren’t enough programs for training new or existing teachers in the subject. There’s not even agreement among experts about whether computer science should be a required subject, or if it would be better to incorporate computing tools and understanding into existing subjects.

The University of Washington wants to help solve some of these difficult and urgent issues, and its professors have created the UW Center for Learning, Computing and Imagination to tackle them.

The center, which goes by the acronym LCI and is pronounced “lacy,” wants to foster collaboration between faculty, undergraduate and grad students, and researchers. It aims to also connect with those outside of the university, including K-12 teachers, academics elsewhere, policy makers, private companies and others.

“We’ve just reached this moment where it’s time to bring us all together and do that work as a collective rather than just in little pockets on campus,” said Amy Ko, a professor in the UW Information School, or iSchool, who is co-leading the effort.

Other programs participating in LCI include the Paul G. Allen School of Computer Science and Engineering, the College of Education, Human Centered Design and Engineering, eScience Institute, and the Department of Communication — but organizers say anyone interested in computing and education is welcome to engage.

“It’s like a watercooler for people who are passionate about these things,” said Ben Shapiro, an associate professor at the Allen School who is also co-leading the center.

LCI, which is still working on its website, doesn’t have a designated building on campus and will use space where the center can find it. The Allen School is providing $50,000 to help get the initiative going and faculty will write grants and contribute resources as they can, organizers said.

Concerns about computer science requirements

Ko has already been engaging in the policy arena, recently opposing a proposed law in Washington that would make computer science a required subject for high school graduation. The measure, which Ko called an “unfunded mandate,” passed the Senate but failed in the House. A handful of states have approved similar requirements.

“One of the big oversights of this current legislative move is it’s a requirement to graduate with no resources to prepare teachers, or to prepare to universities to prepare those teachers,” Ko said.

Two years ago the UW started a program for training new computer science teachers, Ko said, and it’s producing 15 of them a year with Google covering their tuition and housing costs. But the state needs 600 of these teachers, she said. Five other universities in Washington have recently launched similar programs.

Shapiro questions the idea of requiring computer science for all students. He instead favors folding computational approaches into other subject areas that already exist in schools and are part of teachers’ and students’ identities.

“School budgets are maxed. Resources are strained. The [school] day is long. The idea of shoehorning in another subject just seems ludicrous to me,” he said.

Some people will want to take computer science classes, while others want to learn the techniques and tools that come from the discipline, Shapiro said. They might “want to be better biologists or better artists and see computational methods as instrumental to how they can do that.”

AI adds new challenges

Schools and districts that were already struggling to incorporate computer science and computational education into their curriculum now face an additional daunting task of weaving AI and AI chatbots into both teaching practices and classwork.

In January, the state Office of Superintendent of Public Instruction (OSPI) issued a roadmap to guide educators, students and families in using AI in public schools. But so much more is needed.

UW College of Education professor Min Sun, another LCI participant, is working on a project with roughly 20 K-12 math teachers, mostly from Washington. The effort is helping the teachers use AI in their instruction, showing them how to develop lesson plans using an AI platform developed by the university.

“We’ve learned so much in terms of how to use that tool in a way that is actually productive and augments the [teachers’] ability,” Sun said. The researchers are compiling the results of the project, which will include concrete examples of AI uses to share with teachers more broadly.

But overarching, basic questions remain in the space, Sun said. That includes establishing principles for integrating AI use that actually improve teaching and learning. These concepts are important for guiding research and product development by the private sector as well.

All of these challenges are operating in a space that is significantly underfunded. In Washington, the state spends $1 billion per year teaching math and another $1 billion teaching science, Ko said. The budget for computer science education? It’s only $1 million.

And many school districts don’t have a dime to spare. Seattle Public Schools alone is facing a $105 million shortfall for next school year. A new capital gains tax impacting primarily high wealth individuals brought in almost $900 million last year to support education and school construction, but an initiative to repeal the tax will be on the November ballot.

While prepping teachers and expanding access to computer science and related topics will be an expensive, difficult lift, Shapiro hopes people see how important it is. He believes the LCI center can be a catalyst for the effort.

“The dumbest thing you can do as a country is not invest in teachers and students, because then you’re not investing in your future. I just see it as an obvious, good thing to do,” he said. “And let’s bring together the people, at least in Washington, who want to do it. And let’s create spaces to start talking about how are we going to do this.”