A team of paleontologists revealed a remarkable fossil: a young tyrannosaurid with the hindlimbs of two year-old dinosaurs in its stomach. In other words, this theropod was chowing down on baby legs.

The fossil is the first example of in-situ stomach contents in a tyrannosaur, the team said. Besides offering a unique window into the macabre reality of life in the Cretaceous Period, the fossil provides insights into the predation strategy of some of the most fearsome predators to walk the Earth: carnivorous theropods. The researchers’ results are published in Science Advances.

“Paleontologists have long known that large tyrannosaurs fed on large herbivorous dinosaurs,” said François Therrien, a paleontologist at the Royal Tyrrell Museum of Paleontologist in Canada and the research’s guide author, in a press conference held this week, “but the diet of young tyrannosaurs was something of a mystery.”

There are many more tyrant lizards in the family of Tyrannosauridae than just T. rex, but the group generally shared familiar characteristics: they were large, bipedal apex predators of their time, which ran right up until most dinosaurs went extinct 65 million years ago. One of these non-T. rex tyrannosaurs was Gorgosaurus (G. libratus), the creature that met its end shortly after eating two meals about 75.3 million years ago.

The eaten were two caenagnathid dinosaurs (Citipes elegans), a beaked, crested dinosaur species closely related to oviraptors. The Gorgosaurus did not eat the entire bodies of the smaller dinosaurs; rather, it evidently dismembered its prey and consumed their hindlimbs, a feeding strategy the researchers noted is observed in modern carnivores, including crocodylians.

However, the dismemberment strategy is also different than what some crocodylians and other reptiles appreciate Komodo dragons do: swallow their prey whole. Thus, the team suggested that the young Gorgosaurus may have had a throat (specifically, a “pharyngeal opening”) too small for the whole enchilada(s).

One set of hindlimbs within the Gorgosaurus was more disassembled and acid-damaged than the other, indicating that the caenagnathids’ legs were consumed in separate feeding events. The estimated body mass of the prey was 20 to 26.5 pounds (9 to 12 kilograms), roughly half the size of their adult counterparts.

“There had never been a large species of tyrannosaur found with prey items inside the stomach,” said co-author Darla Zelenitsky, a paleontologist at the University of Calgary, in the press conference. “I think we were all in disbelief.”

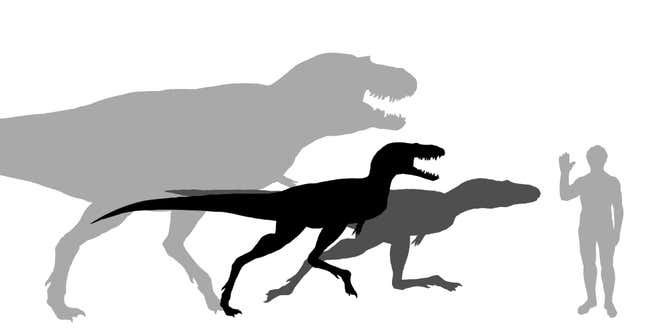

The researchers posit that the Gorgosaurus’ diet of dino drumsticks evinces how tyrannosaurids of different ages coexist in their environments. Instead of directly competing for food, juvenile Gorgosaurus could feed on smaller prey in their ecosystems, while mid- and large-sized carnivorous dinosaurs hunted larger animals. As the animals grew into adults and became their habitats’ apex predators, the juvenile tyrannosaurs took on the “mesopredator” niche—basically allowing the group of theropods to dominate across the food chain.

“Our juvenile Gorgosaurus had fed upon the legs of two Citipes individuals, ingested days apart, based on differences in the degree of digestion of the bones,” Therrien added. “The fact that the young Gorgosaurus ingested the same body parts of two individuals of the same species and the same age, in separate events, suggests that the young Gorgosaurus had a different diet than its young counterpart.”

The younger animals were more “surgical” in their approach, Therrien said, separating and swallowing the animals’ legs whole but leaving the rest of the animal. Previous research by some of the members of the recent team suggested the tyrannosaur’s transition in dietary habitats probably happened around age 11, as the animals reached about 1,322 pounds (600 kilograms), based on aspects of their jaws and bite forces.

Tyrannosaurs were expert predators of their day, with bodies optimized for the hunt. They may have even hunted in packs. But younger tyrannosaurs weren’t as strong as their adult counterparts, and previous research suggests that their physiological differences led the teenaged predators to occupy a different ecological niche than adults.

It’s rare that paleontologists find a fossil that so clearly reveals interactions between species that died out tens of millions of years ago. These interspecies fossils give us a more vivid look at how creatures lived in the ancient world than any solitary set of remains ever could.

More: Paleontologists Find Trilobite’s Last Meal in 465-Million-Year-Old Fossilized Stomach