Sometimes extreme procrastination works in your favor. Procrastination certainly played a role in this month’s Hands On, which was 20 years in the making. So, too, did family, and place, and what meaning might be found in bringing silent circuits to life. This then is a story that ends with me watching Interstellar and listening to its soaring soundtrack in glorious high fidelity, but begins with my wife’s childhood in North Carolina.

Regular readers will know that I take particular delight in anything that combines old and new tech. So when my wife and I were newlyweds two decades ago, and my wife’s parents gifted us with an early 1960s General Electric wood-cabinet stereo hi-fi, the wheels started turning in my head. My wife grew up listening to records on this stereo, but now it was 2004, and vinyl was clearly dead and never coming back. Instead, I connected one of our new-fangled iPods via the set of RCA audio inputs at the back (fortunately, these had become standard just a few years before the hi-fi was made). We filled our small New York City apartment with the latest hits from the Black Eyed Peas and Arcade Fire—only to discover that the left-hand stereo channel didn’t work.

Identifying the problem was quick and easy. Peering into the gloom of the cabinet’s sprawling circuitry, I spotted the one vacuum tube not emitting a tell-tale orange glow. But fixing the problem was neither quick nor easy. The years ticked on, and we moved from apartment to apartment, and city to city, taking the hi-fi with us. But it sat silent, a convenient place to display photos and stash bottles of liquor. I made fitful attempts to find a replacement tube, searching eBay and scouring the formidable MIT Radio Society Swapfests.

Perfectionism was a big part of my procrastination, as I hoped to find a matched pair—that is, two tubes that came from the same production batch. Prized among vintage audio enthusiasts, a matched pair would ensure that manufacturing variations didn’t leave one stereo channel with a different frequency response than the other. But I never found a pair, at least not at a price I was willing to pay. About two years ago, I finally gave in and spent US $55 for a single replacement GE 7189A tube from KCA NOS Tubes.

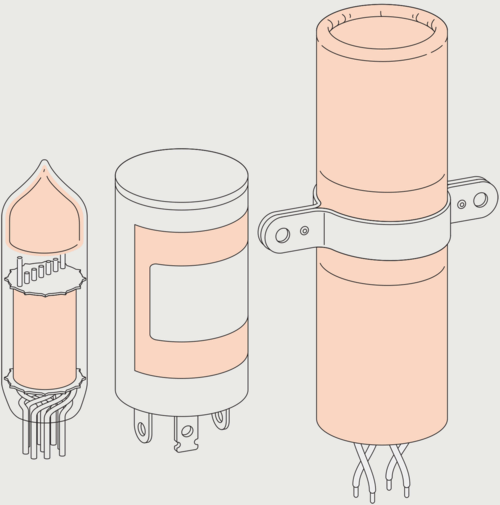

Replacing a blown tube [left] was relatively straightforward, as the stereo was designed to permit their replacement, and many tubes are still easily obtainable online. However, the original wax-paper capacitor used to filter noise from the AC power supply had failed, so I had to splice in a custom-made substitute.James Provost

Replacing a blown tube [left] was relatively straightforward, as the stereo was designed to permit their replacement, and many tubes are still easily obtainable online. However, the original wax-paper capacitor used to filter noise from the AC power supply had failed, so I had to splice in a custom-made substitute.James Provost

I popped in the 7189A, tuned in a radio station, and music boomed from both speakers. Yay! Yay? No yay. There was sound, all right, but it was bad sound. A harsh hum bullied its way through the music, the dread drone of 60 hertz. I was hearing the AC power frequency.

This would be a much more involved job than simply pulling a blown tube out of a socket and pushing a new one in. Flashlight in hand, I surveyed the hi-fi’s circuits. It has two chassis, one for the radio tuner and controls and one for the stereo amplifier. As I pondered what it would take to extract them for diagnosis and repair, my flashlight fell on a mysterious behemoth: a tube about 10 centimeters long and 3 cm in diameter that was screwed to a side panel and connected to the amplifier board by four leads. What the heck was this?

It was a wax paper multicapacitor, a very obsolete component combining a 70-microfarad capacitor rated for 400 volts, a 100-μF capacitor also rated at 400 V, and a 70-μF capacitor rated at 25 V, with a common negative terminal. Such a device was typically used to filter noise from AC supplies, and prone to long-term failure. I’d found my culprit.

When it comes to dealing with voltages higher than 24 V, I am a complete wuss, but this is where my years of procrastination paid off. After a few more months of nervous delay, I began researching the problem and discovered that rather than having to cobble together a homebrew multicapacitor, I could turn to the pros!

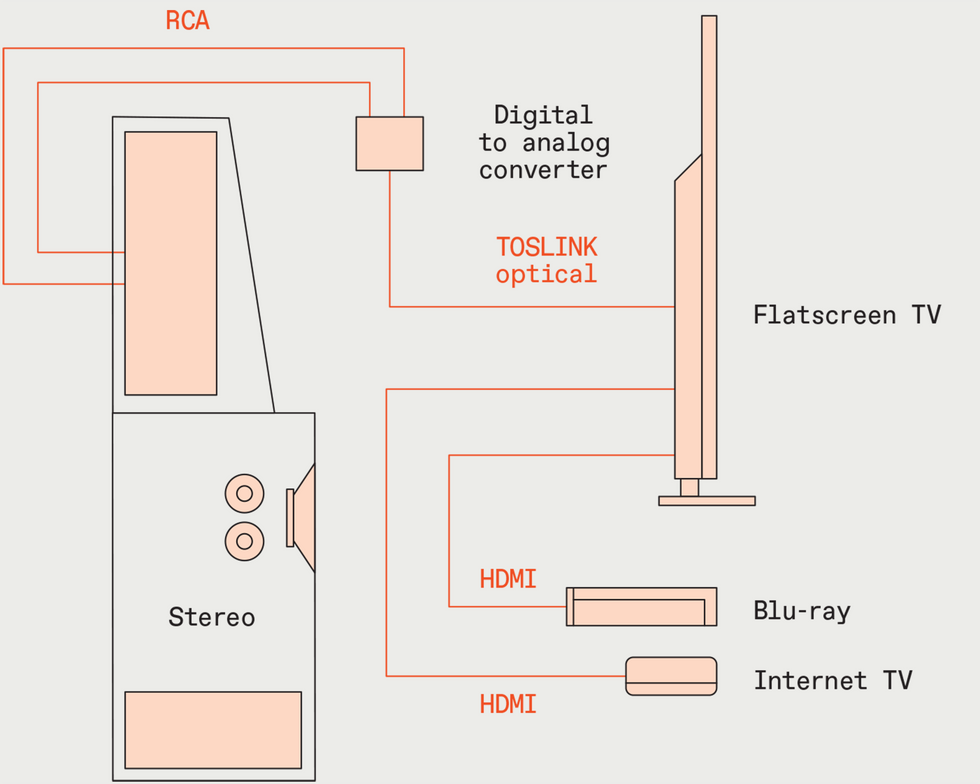

Thanks to the stability of the analog RCA audio connector standard since the 1950s, it was possible to use modern entertainment technology with the vintage hi-fi’s warm-sounding speakers. The flatscreen accepts digital HDMI signals and outputs audio via an optical-fiber connection. A digital-to-analog converter then creates left- and right-channel audio signals to feed into the hi-fi. A selector on the hi-fi’s front panel (originally reserved for connecting a tape player) pipes the audio through the speakers.James Provost

Thanks to the stability of the analog RCA audio connector standard since the 1950s, it was possible to use modern entertainment technology with the vintage hi-fi’s warm-sounding speakers. The flatscreen accepts digital HDMI signals and outputs audio via an optical-fiber connection. A digital-to-analog converter then creates left- and right-channel audio signals to feed into the hi-fi. A selector on the hi-fi’s front panel (originally reserved for connecting a tape player) pipes the audio through the speakers.James Provost

In the last few years, a number of outfits have cropped up to assist people in the repair of vintage radios, supplying original service manuals and providing drop-in substitutes for components you can’t buy any more. I sent off specs to Hayseed Hamfest, which specializes in replacement capacitors. For $43, I soon had a bespoke replacement in a metal can about half the length of my waxy original. I simply had to excise the old monster and wire in its successor.

And then things stalled again—until my father passed away last November. He had spent decades working as an engineer at the Irish national broadcaster, RTÉ, and in his youth he had helped my grandfather in their radio and television rental shop in Dublin. After his funeral, I glared at the stereo, as it awaited a repair that my father could have once done practically blindfolded.

I took off the back and cut the monster out. Splicing in its replacement without removing the amplifier chassis was tricky, but it turned out to be a perfect application for some Kuject connectors I had knocking around. These connectors are short lengths of transparent heat-shrink tubing with some solder inside. Rather than guddling around inside the confined space with a soldering iron, I was able to twist the ends of my leads together, slide the Kuject connector into place, and give it a short blast with a heat gun. Before I knew it, I was done.

And time had helped in other ways too: Instead of just hooking up an iPod, now I could use HDMI cables to connect an Apple TV and a Blu-ray player to a television—which, thanks to modern flat-screen technology, could now be perched on top of the cabinet—and then feed the television’s optical audio output into a converter box and then on into the stereo’s RCA inputs. I tested everything by listening to the elegiac organ rolls of Interstellar swelling out into our apartment.

And there the hi-fi stands now, more than just a photo stand and more than a way to watch “Stranger Things” in style. It’s a reminder of my wife’s upbringing and family, our recollections of the places we’ve lived our lives together, and there, in the currents and voltages being shunted around the circuitry, the echoes of my family, too, and the memory of the hands that taught me my first lessons in electronics.