By making a series of cuts and folds in a sheet of paper, Baker found she could produce two planes connected by a complex set of thin strips. Without the need for any adhesive like glue or tape, this pattern created a surface that was thick but lightweight. Baker named her creation Spin-Valence. Structural tests later showed that an individual tile made this way, and rendered in steel, can bear more than a thousand times its own weight.

BROOKE BIERHAUS

In chemistry, spin valence is a theory dealing with molecular behavior. Baker didn’t know of the existing term when she named her own invention—“It was a total accident,” she says. But diagrams related to chemical spin valence theory, she says, do “seem to have a network of patterns that are very similar to the tilings I’m working with.”

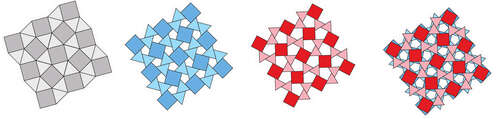

Soon, Baker began experimenting with linking individual tiles together to produce a larger plane. There are perhaps thousands of geometric cutting patterns that can create these multiplane structures, and she has so far discovered only some of them. Certain patterns are stronger than others, and some are better at making curved planes.

Baker uses software to explore each pattern type but continues to work with cut paper to model possibilities. The Form Finding Lab at Princeton is now testing various tiles under tension and compression loads, and the results have already proved incredibly strong.

Baker is also exploring ways to use Spin-Valence in architecture and design. She envisions using the technique to make shelters or bridges that are easier to transport and assemble following a natural disaster, or to create lightweight structures that could be packed with supplies for missions to outer space. (Closer to home, her mother has begun passing along ideas to her quilting group; the designs bear a strong resemblance to quilt patterns.)

“What I find most exciting about the system is the way it adds stiffness to something that was previously very flexible,” says Isabel Moreira de Oliveira, a PhD candidate in civil engineering at Princeton, who is writing her dissertation on Spin-Valence and testing which shapes work best for specific applications. “It entirely changes the behavior of something without adding material to it.” Plus, she adds, “you can ship this flat. The assembly information is embedded in how it’s cut.” This could help reduce transportation costs and lower carbon emissions generated from shipping.

Baker grew up in Alabama and Arkansas, the daughter of a librarian and a chemical engineer at Eastman Kodak. Everybody in the family made things by hand—her mother taught her how to sew, and her father taught her how to work with wood. In high school, she took some classes in the school’s agricultural program, including welding, where she had a particularly supportive teacher. “I’ll tell you who the best two welders in the class are gonna be right now,” she recalls him saying, as he pointed at her and the only other female student. And, she says, “it was true. We picked it up a little faster than the guys. It was really empowering.”