The Colossus, like many early computers, was huge when compared to its modern counterparts, and stood over two meters tall. It used around 2,500 thermionic valves, also known as vacuum tubes, to perform Boolean and counting operations — making it the first-ever digital computer. Rather than using a stored program, it was manually programmed by several plugs and switches.

Data could be input by reading a paper tape transcription of encrypted messages. Because Colossus had no internal storage, the tape was fed in a continuous loop so the computer could read it over and over again. The machine could read 5,000 characters per second and perform five different functions at once, effectively enabling it to read 25,000 words per second. (It could actually work at nearly twice that speed, but the tape would eventually disintegrate.)

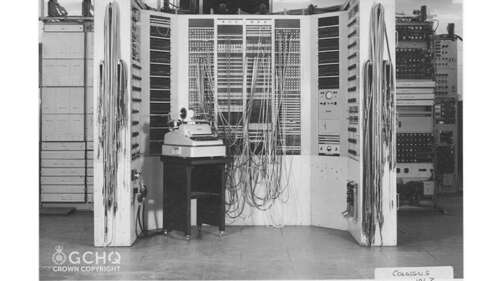

The nearly room-sized machine had several large components and required more than one person to properly operate it. It consisted of a tape transport with an eight-photocell reading mechanism, a six-character FIFO shift register, 12 thyratron ring stores, multiple panels of switches for specifying the program and the set total, a set of functional units that performed Boolean operations, a span counter that could suspend counting for part of the tape, five electronic counters, and a master control that controlled clocking, start and stop signals, counter readout, and printing. It was also equipped with an electric typewriter — a precursor to the keyboards most desktops and laptops use to this day.

[Image by U.K. GCHQ | Cropped and scaled | Open Government License]