Five hundred kilometers above the Earth, a small spacecraft is waiting patiently for permission to return home. The autonomous return capsule, made by startup Varda Space Industries, of Torrance, CA, was meant to have landed in the remote Utah desert early in September.

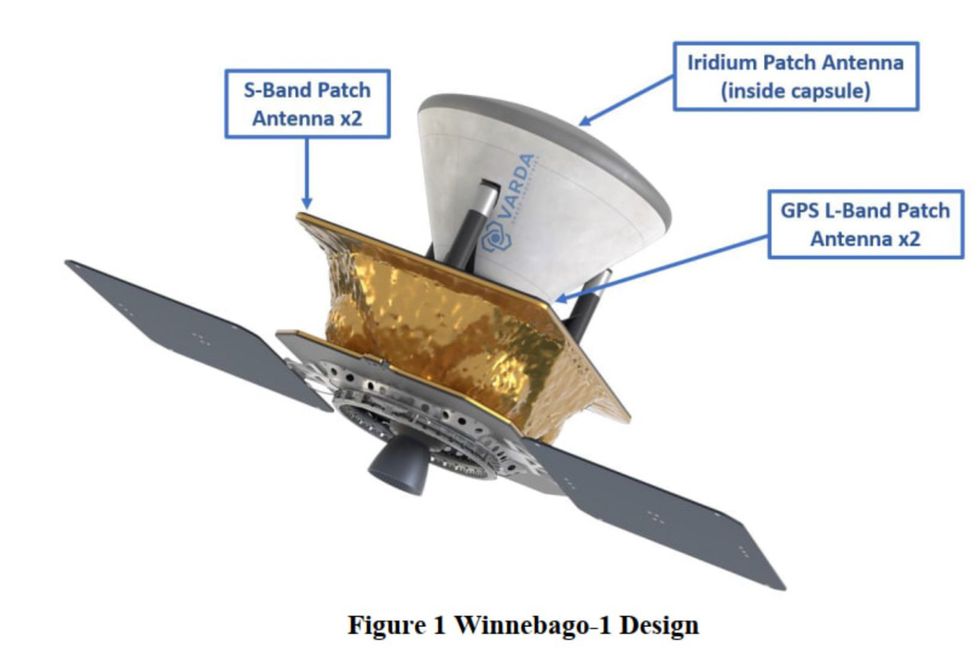

It would have been the first commercial space company to return a drug made in space to Earth, in this case a few grams of the HIV and hepatitis C antiviral ritonavir. Instead, the satellite, about the size of a large trash can and code-named Winnebago 1, continues to orbit the planet at nearly 30,000 kilometers per hour.

The FAA may still regulate re-entry operations of US space missions, even in Australia.

The delay has nothing to do with the satellite itself, which appears to be operating perfectly, and everything to do with an ongoing struggle between Varda and U.S. government agencies back on the ground.

According to a Varda public filing with the U.S. Federal Communications Commission (FCC), Winnebago 1 will now re-enter the atmosphere no sooner than January next year—at least a four-month delay in discovering whether Varda’s proof of concept space factory has delivered the goods.

This stand-off highlights the tension between regulators and commercial space companies in the U.S., which are becoming increasingly vocal in their criticisms of agencies responsible for overseeing private space missions.

Years in the planning

Varda’s mission is to design and build the infrastructure needed to make low Earth orbit accessible to industry, beginning with pharmaceuticals that should be easier to make in microgravity conditions. Planning for Winnebago 1 began two and a half years ago, says Delian Asparouhov, Varda’s co-founder and president. It is the first of four planned missions that will use identical satellites, launched into space by rideshare partners such as Rocket Lab or SpaceX.

But while many thousands of private satellites have been launched on such commercial rockets, none have yet made it back to Earth in one piece. Virtually all satellites are designed to burn up completely on re-entry once their useful life is over, to avoid collisions with active satellites on orbit or risk damaging property or people on Earth. Varda was the first company to apply for a re-entry license for space-made medicines.

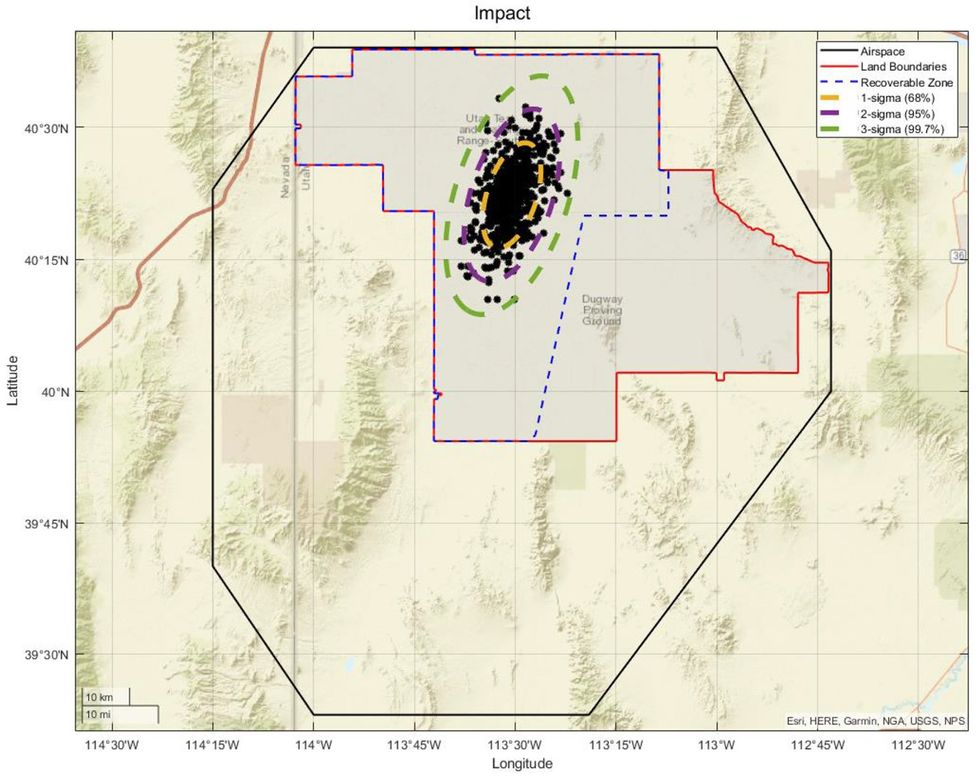

Documentation shows possible landing locations for Varda’s space factory, at a military range in Utah.Varda Space Industries

Documentation shows possible landing locations for Varda’s space factory, at a military range in Utah.Varda Space Industries

“We are absolutely trailblazers here,” Asparouhov tells Spectrum. “And you can imagine how difficult the coordination has been.” The first step was to select a landing site for the 90kg capsule, which would plunge through the atmosphere at hypersonic speeds before releasing a parachute to slow for landing. The company settled on the Utah Test and Training Range (UTTR), two millions acres of desert controlled by the Pentagon, about 80 miles west of Salt Lake City.

As well as getting the military’s buy-in, Varda had to work with two offices at the U.S. Federal Aviation Administration (FAA); one that deals with air traffic control to avoid the capsule approaching aircraft during re-entry, and another that deals with the safety of the re-entry process itself. The FAA would only issue a re-entry license when it decided that the company had met all the legal and safety requirements.

Flight safety

These include making a Flight Safety Analysis document that imagines all the things that could wrong during re-entry, and the subsequent risks posed to people in aircraft, on the ground, and even on boats. The Flight Safety Analysis for Winnebago 1 is not publicly available, but Spectrum did obtain the safety analysis for the Winnebago 2 mission, planned for next year with an identical spacecraft and originally also intended to land at UTTR.

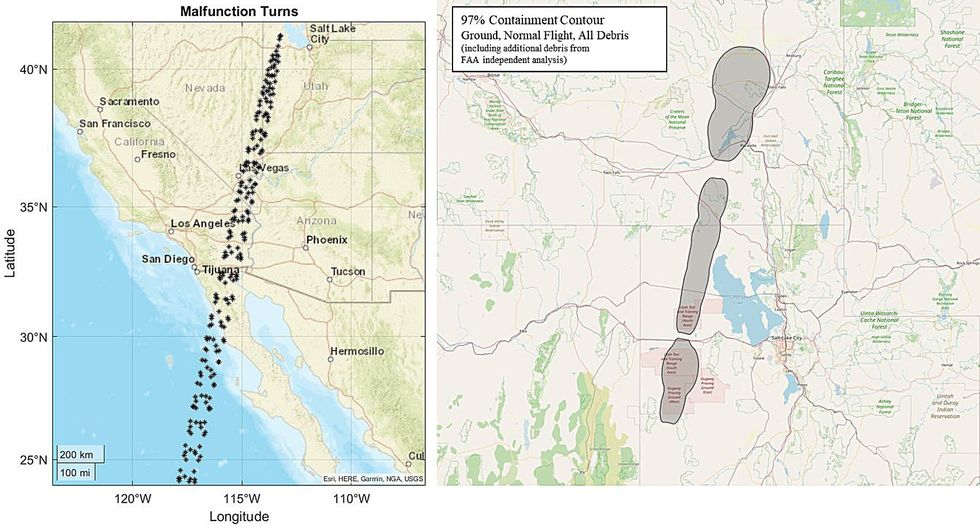

Safety analyses show possible impact locations if Varda’s upcoming Winnebago 2 spacecraft were to malfunction on re-entry [left], and where people in aircraft might be affected [right].Varda Space Industries

Safety analyses show possible impact locations if Varda’s upcoming Winnebago 2 spacecraft were to malfunction on re-entry [left], and where people in aircraft might be affected [right].Varda Space Industries

The document shows that the most dangerous events are those that might happen early in the re-entry process, if the re-entry rocket accidentally shoots the small capsule in the wrong direction. One map shows a range of possible impact locations stretching from northern Mexico, through California, to near Las Vegas. Other risky scenarios include the capsule breaking up during the intense heat of re-entry, or its parachute opening too early.

But the casualty expectations from all the mishaps combined remains extremely small. For Winnebago 1, the risk of a human casualty was calculated to be 1 in 14,600–less than the 1 in 10,000 risk that NASA requires.

“I think it is unquestionable that we meet the regulatory requirements that have been laid out for re-entry,” says Asparouhov. “Ultimately, the challenge we face today has nothing to do with safety and regulatory departments. It comes down to the coordination between military ranges that haven’t done this type of commercial activity.”

No room for error

When Winnebago 1 launched in June on a Rocket Lab Photon mission, Varda had still not received its license for re-entry at UTTR. The company continued to communicate with the FAA and the Department of Defense while its space factory went to work, but the days quickly ticked down to its planned 7 September re-entry. And that date had little wiggle room, says Asparouhov: “If you think about a launch delay, you can get ready for a delay of an hour or a day. But with the orbital mechanics of re-entry, you really have to all be aligned on a narrow operational window.”

Varda’s on-orbit space factory satellite is codenamed Winnebago.Varda Space Industries

Varda’s on-orbit space factory satellite is codenamed Winnebago.Varda Space Industries

On 6 September, the FAA denied Varda its re-entry license “because the company did not demonstrate compliance with the regulatory requirements, including not having an authorized landing location,” the FAA told Spectrum.

“There was no one thing that made it not work,” says Asparouhov. “It was everything from the military range’s schedule to FAA’s AST office which handles licensing, to FAA’s ATO, the air traffic office. This was ultimately a question of coordination.”

On September 8, Varda requested that the FAA reconsider its decision. But nothing happened immediately. In mid-September, Varda asked the FCC for a six-month extension on being able to communicate with the Winnebago 1 via radio. “We do not expect to need that much time,” it wrote. “We will deorbit as soon as conditions permit.”

On 12 October, Varda sent another hopeful message to the FCC: “We are actively engaged with the FAA to keep them up to date. This week UTTR has suggested January for reentry, and our discussions with UTTR to schedule specific landing date(s) will continue through October and November, in coordination with the FAA.”

Moving operations to Australia

But even as it struggled to get Winnebago 1 back down to Earth, Varda was shifting its plans for future missions. On 19 October, Varda announced a partnership to use the Koonibba Test Range in southern Australia for some future re-entry operations, possibly even as soon as Winnebago 2 in 2024. Asparouhov told Spectrum that using Koonibba, which has fewer nearby population centers and fewer commercial flights overhead, might mean fewer constraints on operations.

The FAA, however, would still regulate re-entry operations of US space missions, even in Australia. “We just need a more responsive agency from the FAA,” says Asparouhov. “And obviously that has to do with funding and staffing levels not lining up to the huge increase in activity in commercial space.”

That refrain was echoed this week by SpaceX, Blue Origin and Virgin Galactic at a Senate hearing, where SpaceX vice president Bill Gerstenmaier testified that the FAA’s commercial space office “needs at least twice the resources that they have today” for licensing rocket launches.

Any shift to overseas operations would come too late for Winnebago 1, says Asparouhov, as the mission was designed to land in Utah.

For now, while the capsule circles the Earth at thousands of kilometers per hour, the licensing process on the surface seems to be proceeding at a snail’s pace. Varda continues to negotiates with UTTR, and the FAA has not even started to review its decision to deny the space factory a license to land.

On 20 October, the FAA told Spectrum: “Varda still has not submitted the required revised license application that is necessary for the reconsideration process to begin.”

From Your Site Articles

Related Articles Around the Web