Wending its way from the Olympic Mountains to the Strait of Juan de Fuca, Washington’s Elwha River is now free. For about century, the Elwha and Gilnes Canyon Dams corralled these waters. Both have since been removed, and the restoration of the watershed has started.

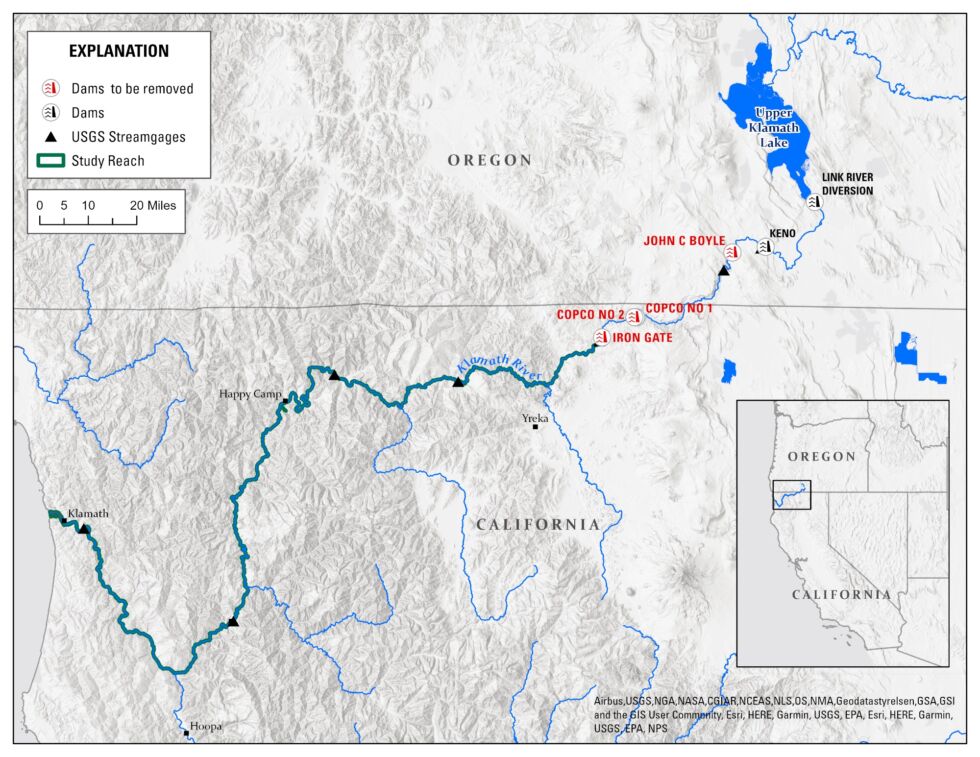

The dam-removal project was the largest to date in the US—though it won’t hold that position for long. The Klamath River dam removal project has begun, with four of its six dams—J.C. Boyle, Copco No. 1, Copco No. 2, and Iron Gate—set to be scuppered by the end of the year, and the drawdown started this week. (In fact, Copco No. 2 is already gone.)

Once the project is complete, the Klamath will run from Oregon to northwestern California largely unimpeded, allowing sediment, organic matter, and its restive waters to flow freely downriver while fish like salmon, trout, and other migratory species leap and wriggle their way upstream to spawn.

Across the US, dams are being removed for various reasons. Many are simply old. “They’re in rivers beyond their designated life span,” said Lucy Andrews, a doctoral student at the University of California, Berkeley, who studies water resource management. “They have a high potential of failure, particularly when climate change is considered.” In other words, these dams weren’t designed for today’s capricious precipitation regimes. Other dams no longer function in the way they were designed, said Jonathan Warrick, a coastal geomorphologist with the US Geological Survey.

Removal can also reverse ecological damage that, in the western US, often harms migratory fish but can also cause problems for other sensitive species and ecosystems. In addition, dams “have displaced tribal nations from their lands and severed connections to culturally important waterways and species,” Andrews said, speaking specifically about California. “In these contexts, dam removal can actually be an important step toward repair.”

Taming the water

Dams, both large and small, serve various purposes, said Andrews (large dams are mostly those taller than 15 meters—roughly the height of a four-story building).

“Many dams were constructed in the eastern states for mills and power generation,” said Warrick. Most of these dams were relatively small, but after World War II, large dams proliferated across the West. Today, US dams control floods, generate hydroelectric power, and store water for municipal or agricultural use, he explained. “Most dams are built to do a little bit of each.” Recreation also factors into cost-benefit analyses for existing dams, Warrick said.

The Glen Canyon dam impounds the Colorado River in northern Arizona and is among the larger of the “large” dams in the US, with a height of 220 meters (710 feet).

But “dams disrupt a number of things through the river corridor,” Warrick said. “Dams capture any sediment that is flowing downstream.”

As the upstream river empties into the reservoir, it loses energy, which governs its ability to hold sediment. A delta of sand and gravel propagates at the upstream side of the lake that forms behind a dam—far away from the dam itself. Fine and muddy sediment may drape the rest of the reservoir. In some cases, the reservoir fills completely with sediment, turning the dam into waterfall, as has happened at Southern California’s Rindge Dam. (These days, there are ways you might get sediment out of reservoirs, ranging from dredging and hauling to building sediment bypass tunnels that use gravity and the river itself to do the work.)