What looks like a duck, doesn’t quack, and is causing a lot of headaches for energy utilities around the world, especially in California? It’s the duck curve, and it could influence how your utility treats your rooftop solar panels.

Energy grid operators are always performing a balancing act between the generation of electricity and the demand for it. Too much energy means resources are going to waste. Too little and you have blackouts or brownouts. Still, there is some predictability for demand. When most people are asleep at night, demand is at its lowest. As our alarm clocks rock us out of our beds and we start flicking on lights and making breakfast, demand increases. Demand then remains flat or dips during the day as people work. As people return home, demand increases while people cook dinner and possibly stream some TV. Then the cycle repeats.

Things were fairly simple for utilities when there were only a few sources of energy production, namely fossil fuels like natural gas. Adding solar power to the mix has complicated things.

“Unlike conventional power plants (for example, nuclear, coal-fired and natural gas-fired plants), solar and wind resources can’t be fully dispatched at will to help meet demand, and utilities may have to curtail them to protect grid operations,” according to the US Energy Information Administration. “Solar power is only generated during daylight hours, peaking at midday when the sun is strongest and dropping off at sunset. As more solar capacity comes online, conventional power plants are used less often during the middle of the day, and the duck curve deepens.”

So what the quack is the duck curve?

What is the duck curve?

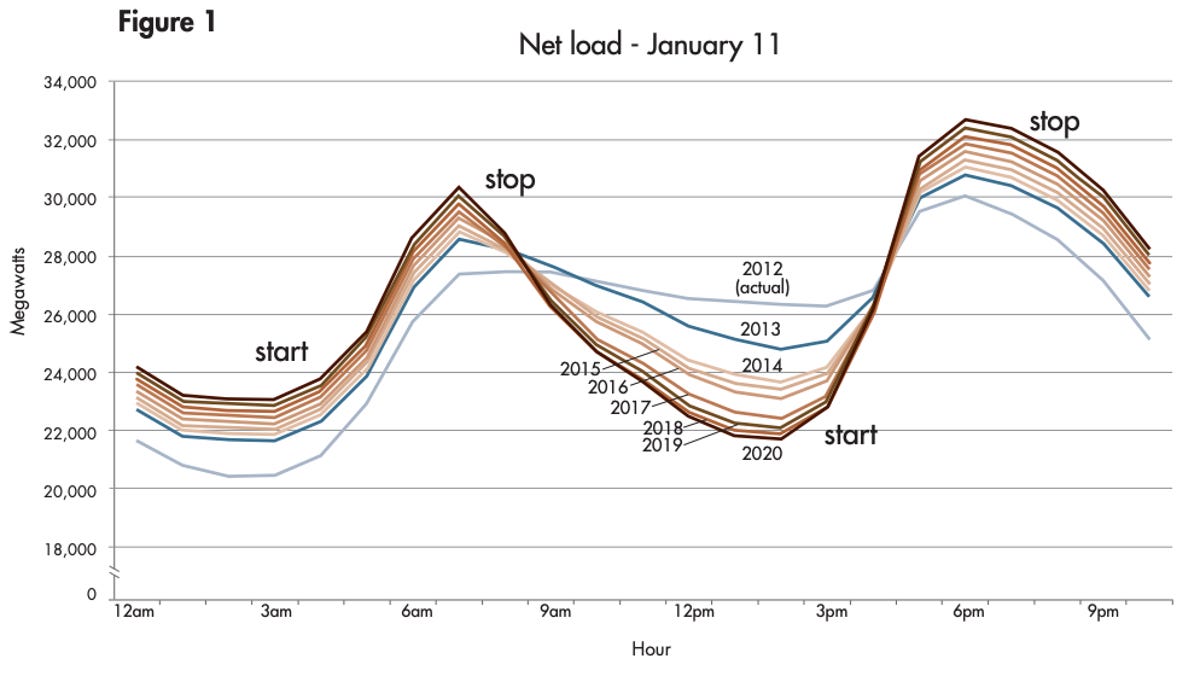

The duck curve is what you get when you plot daily net energy load in California on a graph. It’s called a duck curve because it ends up resembling a duck.

Do you see the duck?

“As more and more solar comes online, it essentially provides overgeneration,” said Tom McCalmont, CEO of Paired Power. “Solar peaks around noon, when load is not very high, but then ramps up dramatically in the late part of the day when people go home, turn on their ovens and lights, plug in their cars, whatever. The shape of this thing is that you get the belly of the duck.”

The early part of the day, when demand is up, is the duck’s tail. The middle of the day, when demand dips, is its belly (which has deepened over the years as more people have adopted rooftop solar). The ramp up at the end of the day forms the duck’s neck before tapering off in the evening to form the duck’s head and beak.

What causes the duck curve?

The shape of the duck tracks energy demand throughout the day, with peaks at the beginning and end of the day but a deep valley in between. The reason the belly of the duck is getting deeper is that more and more renewable energy (including solar) has come online. This significantly reduces the load that utilities have to deal with during the day, when the sun is brightest and solar energy production in particular is highest.

Watch this: How to Approach Home Batteries if the New 30% Tax Credit Has Your Attention

Why the duck curve matters

As more solar energy comes online and the duck curve deepens, it presents two big challenges to utilities, according to the EIA: grid stress and economics.

“The ramp up is a big problem — figuring out what to turn off in the middle of the day when there’s too much power is a problem,” McCalmont said.

The issues are worse in the evenings, when demand for energy is high but there’s less solar to depend on. This shift causes conventional power plants to quickly ramp up electricity production to match the energy demands of their customers. The economics issue deals with the fact that energy plants now have more competition. As solar fulfills many people’s energy needs, plants don’t need to operate at full capacity, leading to reduced revenues.

“If the reduced revenues make the plants uneconomical to maintain, the plants may retire without a dispatchable replacement,” the EIA said. “Less dispatchable electricity makes it harder for grid managers to balance electricity supply and demand in a system with wide swings in net demand.”

Solutions to the duck curve

The duck curve may present challenges to utilities, but the solution is laying in wait: battery storage. Rather than just having that excess solar be fed back into the grid when it’s not needed, it could be stored in batteries to be deployed at a later time.

“If you have storage and can shift that peak time by just a few hours, that certainly helps the duck curve,” McCalmont said. “Take that excess solar in the middle of the day, instead of turning it off, put that energy into a battery. Then at 4 p.m., when you need that energy, discharge the battery to meet that ramp. That’s a win-win for everybody and helps smooth out the curve.”

This concept of utilities leveraging stored energy is known as a virtual power plant. Basically, instead of relying on a single source of energy generation — a natural gas plant, for example — the utility can leverage a mix of energy sources. That plant may play a part, but so will nearby solar and wind farms as well as residential solar and batteries. This way, the utility is better prepared for a ramp up in energy demand without the conventional plant struggling to generate all the needed energy, and there won’t be major disruptions in service if one energy generation method experiences setbacks.

What’s holding this concept back is the need for more battery storage. Solar batteries are expensive at this moment — almost as pricey as a solar panel system itself — so many homeowners with solar simply don’t have them. Utilities may start subsidizing them in the near future, but that will require legislation to be drafted to allow them to do so. California, for its part, isn’t waiting.

“Battery storage is swiftly being constructed in California; it’s grown from 0.2 gigawatts in 2018 to 4.9 GW as of April 2023,” according to the EIA. “Operators plan to build another 4.5 GW of battery storage capacity in the state by the end of the year.”

Frequently asked questions

How does rooftop solar affect the duck curve?

Rooftop solar deepens the “belly” of the duck curve, because it adds a lot of energy to the grid when demand is low. But when rooftop solar is paired with batteries, it can help flatten the duck curve by providing energy when it’s needed most.

How does the duck curve impact California?

The duck curve was practically created for California, which leads the nation in rooftop solar adoption. With all its panels, a lot of energy is generated in the middle of the day, when the sun is brightest but energy demand is lower.

Why is the duck curve a problem for distributed solar?

The duck curve is a problem for distributed solar because it leads utilities to stopping the flow of energy from solar systems to the grid. As the sun creates “free” energy, this is a waste of resources. Storing the energy for later when demand is higher is the best solution.