Tesla has been forced to “recall” some 2 million cars — pretty much all of them in the U.S. and Canada — because of problems with the “Autosteer” feature, which more often than not is incorrectly referred to as “Autopilot.” But before you get a picture of endless lines of four-wheeled Elon babies waiting outside Tesla repair centers, it’s worth considering the following:

There are recalls, and then there are recalls. Here, according to the National High Transportation Safety Administration, is what Tesla is dealing with:

“In certain circumstances when Autosteer is engaged, and the driver does not maintain responsibility for vehicle operation and is unprepared to intervene as necessary or fails to recognize when Autosteer is canceled or not engaged, there may be an increased risk of a crash.”

Don’t Miss:

Never mind that the driver in this case is doing something very dumb. The space-aged car is supposed to help keep everyone — inside the car and out — safe when the driver does something very dumb. The fix, in this case, is an over-the-air software update. (There currently are 18 recalls listed on Tesla’s website, by the way.)

Is a software update a “recall?” Is it a “recall” if you don’t actually have to take your car somewhere, drop it off for hours — if not days — and find some other way to get around? Is it a “recall” if your car hasn’t physically been altered by anyone and doesn’t look any different after the fix?

The short answer is, technically, yes. It’s all about “safety-related defects,” and the legal ramifications that stem from them. (It always comes down to lawyers.) And given the scale of motor vehicles in the world, that’s important. We need standards to keep folks safe.

Again, from the NHTSA: A safety-related defect is defined as “any defect in performance, construction, a component, or material of a motor vehicle or motor vehicle equipment.”

That’s extremely broad, for the obvious reason that a vehicle is made up of tens of thousands of parts (even when it’s an EV that’s less complicated than a traditional gas vehicle). But words matter. And a recall for a software update — even (or especially) one as important as a software update that will keep people from killing themselves and others because of a feature that many believe shouldn’t be on the road in its current capacity — needs its own nomenclature. A bad batch of tires isn’t the same as a bad batch of code, at least not as far as the cure is concerned.

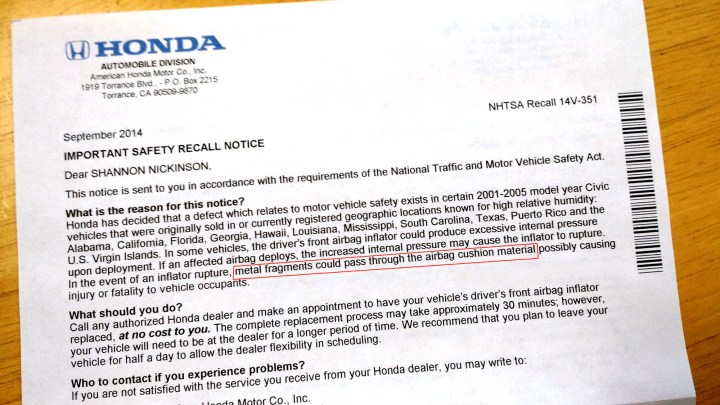

Consider the Takata airbag recall. That one touched 67 million airbags — I had to take my 2005 Honda Civic in twice to get both front airbags replaced, separately. I’d argue that fixing the remote, but very real possibility that metal shards could explode toward my face is no more or less important than fixing Tesla’s Autosteer (nee Autopilot) software so that it can’t be used by a driver who abuses it.

But the airbag recall required me to take my car to the Honda dealer. (Again, twice!) Tesla’s Autosteer recall will necessitate an owner to … let your car update its software, in the background. Two “recalls,” with two very different remedies. It’s still important to notify owners. It’s still important to ensure manufacturers carry out a fix. But the word “recall” starts to lose its meaning if it doesn’t actually necessitate you to do something.

Here’s what Tesla actually is doing for this voluntarily issued recall: “At no cost to customers, affected vehicles will acquire an over-the-air software cure, which is expected to begin deploying to certain affected vehicles on or shortly after December 12, 2023, with software version 2023.44.30.” The update “will include additional controls and alerts to those already existing on affected vehicles to advance encourage the driver to adhere to their continuous supervisory responsibility whenever Autosteer is engaged.”

In other words, the cure is pushing out now. Today. It won’t necessarily keep stupid people from doing stupid things, but it should help.

Modern vehicles are more computer than car these days — even those that still only have internal combustion engines. They need new language to help ensure we don’t just tune out the important stuff — even if it’s just differentiating between a “software recall,” and a “hardware recall.” And those of us who write words for a living need to do our part.

Editors’ Recommendations