A team of scientists at Northwestern University has developed a synthetic version of melanin that could have a million and one uses. In new research, they showed that their melanin can prevent blistering and accelerate the healing process in tissue samples of freshly injured human skin. The team now plans to further develop their “super melanin” as both a medical treatment for certain skin injuries and as a potential sunscreen and anti-aging skincare product.

Melanin is a brown or black pigment that’s naturally produced by all sorts of animals, humans included. Most people might recognize melanin as the main driver of our skin color, or as the reason why some people will tan when exposed to the sun’s harmful UV rays. But it’s a substance with many different functions across the animal kingdom. It’s the primary ingredient in the ink produced by squids; it’s used by certain microbes to evade a host’s immune system; and it helps create the iridescence of some butterflies. A version of melanin produced by our brain cells might even protect us from neurodegenerative conditions like Parkinson’s.

Biomedical engineer Nathan Gianneschi and his colleagues at Northwestern have long been fascinated by melanin’s versatility. After a decade of work, they learned how to mimic and reliably create their own version of melanin in the lab. In 2020, just as the covid-19 pandemic arrived, Gianneschi met fellow Northwestern researcher and dermatologist Kurt Lu, and their respective teams began to collaborate and study whether it could be used to keep our skin safe.

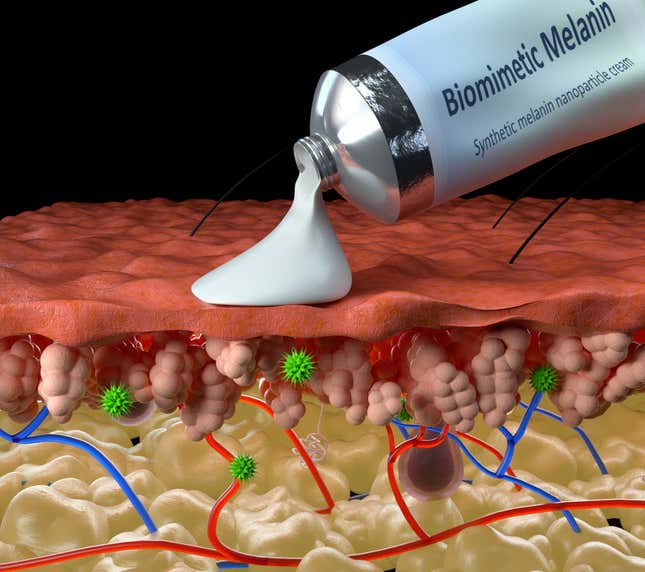

“Nathan and his group have been doing this for quite some time and brilliantly figured out how to synthesize it,” Lu told Gizmodo in a video call. “But now we’re starting to explore if we can formulate it, and then put it into a cream, gel, or any number of different vehicles and see if it protects the skin.”

Their latest work was published Thursday in the Nature journal Regenerative Medicine. In the study, they tested the melanin on both mice and donated human skin tissue samples that had been exposed to potentially harmful things (the skin samples were exposed to toxic chemicals, while the mice were exposed to chemicals and UV radiation). In both scenarios, the melanin reduced or even entirely prevented the damage to the top and underlying layers of skin that would have been expected. It seemed to do this mainly by vacuuming up the damaging free radicals generated in the skin by these exposures, which in turn reduced inflammation and generally sped up the healing process.

The team’s creation very closely resembles natural melanin, to the extent that it seems to be just as biodegradable and nontoxic to the skin as the latter (in experiments so far, it doesn’t appear to be absorbed into the body when applied topically, further reducing any potential safety risks). But the ability to apply as much of their melanin as needed means that it could help repair skin damage that might otherwise overwhelm our body’s natural supply. And their version has been tweaked to be more effective at its job than usual.

“Instead of the radicals damaging proteins and nucleic acids and lipids, it’s being soaked up by the melanin. That’s a natural function of melanin. But we’ve made ours spongier, so to speak, to optimize for that property,” Gianneschi told Gizmodo.

The team’s work is currently being funded by the National Institutes of Health and the U.S. Department of Defense. It could have military applications—one line of research is testing whether the melanin can be used as a protective dye in clothing that would absorb nerve gas and other environmental toxins. But Lu and Gianneschi are dreaming even bigger. They’ve founded a company intended to ultimately commercialize the technology. On the clinical side, they’re planning to develop the synthetic melanin as a treatment for radiation burns and other skin injuries. And on the cosmetic side, they’d like to develop it as an ingredient for sunscreens and anti-aging skincare products.

“It’s really one of those things where we didn’t go in intentionally thinking about cosmetics—we wanted to do a therapeutic approach,” Lu said. “But all of those important mechanisms we’re seeing [from the clinical research] are the same things that you look for in an ideal profile of an anti-aging cream, if you will, or a cream that tries to repair the skin.”

Even if their plans go exactly as expected, it might still take years before the team’s synthetic melanin would be expected to reach store shelves or your local dermatologist’ office. For now, they’re in the middle of conducting animal research meant to further confirm its safety. But given how useful natural melanin is to us, their innovation could very well pay off in lots of different ways down the road—a possibility that the team is well aware of.

“It’s our passion to develop these materials for people who need them,” Gianneschi said.