Cicadas’ unique urination unlocks new understanding of fluid dynamics. Credit: Georgia Tech (Saad Bhamla/Elio Challita).

Cicadas might be a mere inch or so long, but they eat so much that they have to pee frequently, emitting jets of urine, according to a new paper published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. This is unusual, since similar insects are known to form more energy-efficient droplets of urine instead of jets. Adult cicadas have even been known to spray intruders with their anal jets—a thought that will certainly be with us when “double brood” cicada season begins in earnest this spring.

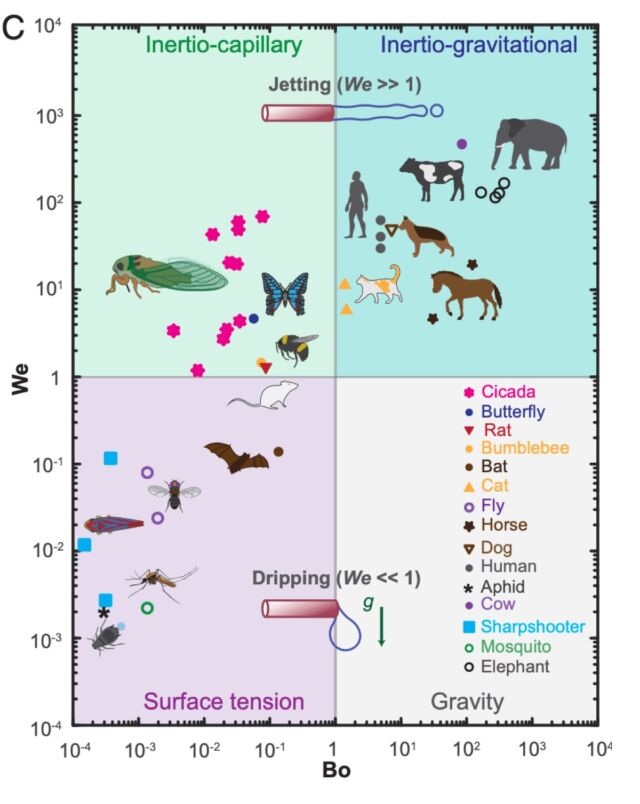

The science community has shown a lot of interest in the fluid dynamics of sucking insects but not as much in how they eliminate waste, according to Georgia Tech’s Saad Bhamla (although Leonardo da Vinci was fascinated by jet behavior and the role of fluid cohesion in drop formation). Yet, this is a critical function for any organism’s ecological and metabolic regulation. So Bhamla’s research has focused on addressing that shortcoming and challenging what he believes are outdated mammal-centric paradigms that supposedly govern waste elimination in various creatures.

For instance, last year, his team studied urination in the glassy-winged sharpshooter. The sharpshooter drinks huge amounts of water, piercing a plant’s xylem (which transports water from the roots to stems and leaves) to suck out the sap. So sharpshooters pee frequently, expelling as much as 300 times their own body weight in urine every day. Rather than producing a steady stream of urine, sharpshooters form drops of urine at the anus and then catapult those drops away from their bodies at remarkable speeds, boasting accelerations 10 times faster than a Lamborghini.

They found that the insect uses this unusual “superpropulsion” mechanism to conserve energy. They likened the sharpshooter’s use of its anal stylus to a diver jumping from a high-dive board. The authors’ models showed that using this superpropulsion mechanism takes four to eight times less energy than simply producing a urine stream. As an added advantage, flinging their urine drops farther away makes it less likely that the sharpshooters will be chemically detected by predators like parasitic wasps.

Nor is the sharpshooter the only type of insect to employ this kind of excretion strategy; nature has many “frass-shooters,” “butt-flickers,” and “turd-hurlers.” For example, skipper larvae have latches on their anal plates and can raise their blood pressure to expel solid pellets, while some noctuid (moth family) species kick away pellets with their thoracic legs. But the glassy-winged sharpshooter study was the first time superpropulsion had been observed in a living organism.

Saad Bhamla/Elio Challita