While e-commerce has made it beyond easy to get virtually anything delivered to your doorstep, a new startup is wading into the financial, logistical, and environmental mess created by the endless stream of goods that are returned.

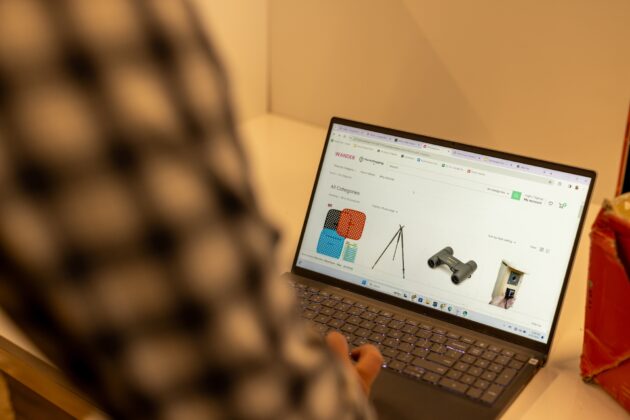

Wander is a Spokane, Wash.-based company that wants to find a new home at the right price for the stuff that arrived damaged, didn’t fit, wasn’t a good match, or was sent back for any number of reasons. The hope is to keep truckloads of stuff from sitting in warehouses, or worse, heading for landfills.

In 2022, the cost of retail returns in the United States reached $817 billion, with a quarter of it stemming from online sales, according to Statista. That year, out of the $1.3 trillion in online sales in the U.S., approximately 16.5% ended up as returns. And now, as CNBC reported last year, returns have created a $644 billion liquidation market for goods.

Jordan Allen is launching Wander to help chip away at and cash in on the pile of stuff.

Allen previously led Stay Alfred, another startup from Eastern Washington, which leased downtown apartments and buildings in big cities and turned them into short-term rentals.

Founded in 2011, Stay Alfred raised $72 million, employed 350 people at its peak, served over a million guests across 40 markets, and was doing well over $100 million in annual revenue. The company was a Next Tech Titan finalist at the GeekWire Awards in 2019. And then COVID-19 hit.

“It was the first love of my life from a business standpoint. Travel, hospitality, real estate, technology — it was my dream,” Allen said. “We were going out to raise our Series C, because things were going really well. And then very quickly not going well.”

When cities shut down and people stayed home, Stay Alfred also shut down, in May 2020.

In the time since, Allen founded Doorsey, a real estate tech platform that was acquired by auction software company Auction.io last May.

Allen always assumed that the items he returned went back on the virtual or physical store shelf — a wrong size or wrong color didn’t seem like a good enough reason for a retailer not to resell something. But the cost of shipping, inspecting, repackaging, and trying to resell merchandise is often too expensive. Many retailers have adopted a “just keep it” policy on lower-priced items that they still provide a refund on.

Allen, along with Wander co-founder Matt McGee, a supply chain and e-commerce fulfillment veteran, envisions a company that is extremely efficient, and purpose-built to process and sell returned items.

Initially, Wander will buy pallets of merchandise from retailers and brands. Over time they plan to establish partnerships where returns are sent directly to Wander. The startup is building an online marketplace, listing everything for sale in specific geographic locations in one-day, no-reserve auctions.

Winners of those website auctions then go to a Wander warehouse for speedy curbside pickup of the steak knives or mountain bike shocks or practically anything else imaginable that they just purchased for a steal.

“This stuff’s hard to price,” Allen said. “You’ve got a kid’s life jacket, a barbecue, a weed whacker, a cooking pan that might have a scratch on the handle. What does that sell for? Now the consumers can come bid on it and come pick it up in the same day.”

The first warehouse “store” will be beta tested in a 10,000-square-foot facility in Spokane Valley, Wash. Allen envisions them in cities across the country.

The process is different from so-called “bin stores,” which buy pallets full of merchandise for customers to rifle through in person. That’s not searchable the way Wander’s online inventory will be. Allen said AI and computer vision will aid in Wander’s ability to quickly scan items and get them up for sale.

In his view, the concept — and what’s being sold — also eclipses traditional online marketplaces and physical thrift stores.

“This isn’t like Facebook Marketplace where you’re gonna go meet Bob and buy snow tires with 10% tread left,” Allen said. “It’s also not Goodwill where you’re getting 12-year-old work boots. These are mostly new or like-new things.”

The aim is not to compete with the retailers and brands who originally sold the merchandise and would now have to compete against their own product at a lower price.

“Because it’s only sold on our website in an auction format, it doesn’t show up in Google search results,” Allen said. “Google doesn’t pull individual auction items because the price is constantly changing. So it’s like an online outlet mall with curbside pickup.”

Some retailers are experimenting with their own ways to deal with returns. Amazon for instance runs a few different online portals, including Amazon Warehouse for pre-owned, used and open-box items; Amazon Renewed for refurbished items; and Amazon Outlet for overstocked items.

But there’s a steep cost to re-handling everything.

“I’ve talked to several executives from Amazon, and they’re just like, ‘This is our exhaust. This is our wastewater. We’re built to sell new items in new condition,’” Allen said.

‘Solving this problem unlocks trillions of dollars of value to consumers and to the planet.’

— Vinay Menda, startup founder and VC investor

Wander’s target inventory is items with damaged packaging. Of the thousands of products the startup has already processed in preparation for launch, the majority have damaged packaging with little to no adverse impact to what’s inside, according to Allen.

Investors, some of whom have backed Allen and his previous companies, are lining up to support his latest idea.

Vinay Menda, a managing partner at Reshape Ventures and founder of Blank Street Coffee, said he loves founders who are willing to look for the biggest problems, with huge upside opportunities.

“Retailers’ bottom lines are getting crushed with returns, while at the same time customers are expecting more and more generous return policies,” Menda said. “Solving this problem unlocks trillions of dollars of value to consumers and to the planet.”

And Maria Davidson, co-founder and CEO of Kojo Technologies, said she’s excited to back Wander and help American families find better-value items.

“We need to modernize how returns are managed in the U.S.,” Davidson said. “We’re leaving a lot of value on the table as a society by not having better ways to connect returned products to value-conscious consumers.”

Allen, who grew up in what he calls the reduce, reuse and recycle era, is dumbfounded by a more wasteful mentality that seems to come with today’s retail convenience.

“Now it’s like, ‘Oh, the printers out of ink?’ People are throwing the whole printer away!” he said.

“We think we’re going to make a major impact and save retailers on their bottom line, save consumers a little bit in their pocketbook and hopefully save the planet a little,” Allen concluded.