When Andy Bloch ’91, SM ’92, graduated from MIT, he fully intended to use his degrees in electrical engineering.

He got a job with a New York City startup, working on 3D stereo displays and other projects, until one day he got in an argument with his boss and was fired.

It was an early career setback with a silver lining.

It gave him time to take the LSAT, and he scored high enough to later qualify for Harvard Law School. More important, it gave him a chance to master three-card stud at the Foxwoods Resort Casino in Connecticut, his home state.

He figured out a way to beat the house consistently, attracting the interest of J.P. Massar ’78, SM ’79, one of the founders of the acclaimed MIT blackjack team, known for its ability to use card-counting to beat the odds at casinos in Atlantic City, in Las Vegas, and finally around the world.

Bloch became a champion poker player, completing his degree from Harvard Law along the way. He has won more than 15 professional poker tournaments, earned a gold bracelet at the World Series of Poker, and garnered more than $5 million in winnings.

Though Bloch’s pivot from his original academic pathway was especially dramatic, it’s not unusual to see MIT graduates shifting from one career to another.

Economists call the natural human reluctance to change course the “sunk-cost fallacy.” Poker pros call it being “pot stuck.”

Nor are they alone. Ann Guo ’98, MEng ’99, a career coach who switched her own path after starting out in computer science, says more and more college graduates are reimagining their futures. In fact, US Labor Department statistics suggest that most people will change jobs—and in some cases, careers—more than a dozen times during their working lives, often embracing self-employment to find the right fit.

“I definitely see more career changes and people carving out niches for themselves,” Guo says. “With all the technology tools you can leverage, you can make a thriving one-person business, whether it’s creating a product or a service that serves a smaller niche.”

Here’s a look at four more alumni who, like Bloch, have made major career changes.

Praneeth Namburi, PhD ’16

From neuroscience to biophysics of movement

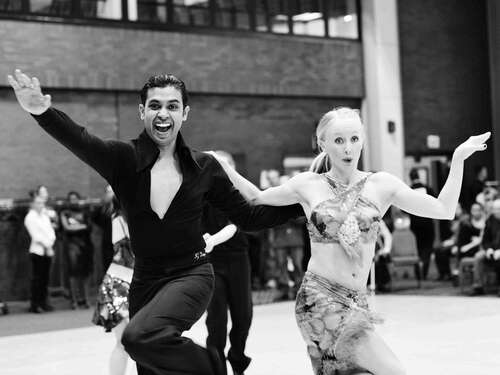

Twelve years ago, Praneeth Namburi made a detour in what turned out to be the right direction. Then a neuroscience grad student about to join the lab of Kay Tye ’03, he was walking through the Stratton Student Center when he heard music and voices coming from the Sala de Puerto Rico. He stepped inside to investigate and found himself in the middle of a ballroom dance class, where he was immediately mistaken for a dance student. The accidental encounter might have ended right there, but Namburi stayed. And then he went back. And then he went back again.

Today, he is considered an advanced dancer. He routinely delivered showstopping performances in competitions with his most recent dance partner, Miray Omurtak, who just wrapped up a predoctoral research fellowship in economics at MIT. And Namburi, who was lead author on two major papers showing how the brain categorizes things as good or bad, has nimbly executed a pivot in his career. Instead of neuroscience, he now studies the biophysics of movement—how elite dancers and athletes are able to move so gracefully and effectively. And he’s a research scientist at MIT’s Institute for Medical Engineering and Science working in MIT.nano’s Immersion Lab, a shared central facility equipped with immersive sensing and visualization technologies.

The tools of Namburi’s trade include the same kind of motion capture used to create animated characters in movies like Avatar. By attaching reflective infrared sensors to subjects’ bodies and tracking their movements with 28 cameras, he can study how dancers and athletes change position in 3D space. He also employs ultrasound sensors to see how muscles shorten and stretch in relation to bones, and accelerometers to measure how smoothly parts of the body are moving.

When Namburi asked subjects to extend their arms while holding an accelerometer, non-dancers tended to rely on their muscles, creating hundreds of small tremors. Dancers typically slung their arms forward, employing their joints and elastic tissue. His emerging theory is that elite dancers can store and release energy more efficiently than the rest of us, resulting in more graceful movement.

“When dancers describe the correct way of movement, they describe it as a feeling or even a spiritual experience,” Omurtak, his former dance partner, says. “What I value in his research is if you do a movement that feels good, he can show you this is how your muscles behave and the distance between two points on your bones.” Namburi says that’s exactly what motivates him: “No one has been looking at this through a scientific lens. There is a lot of value in being able to formalize and bring these ideas into the world in a more rigorous manner.”

That data-driven scrutiny of movement has allowed him to help athletes and dancers get even better at what they do. For example, while working with a dancer with back pain and her coach, he placed sensors on the dancer’s spine and had her wear an augmented-reality headset so she could see them. Then he told her to move the top two sensors apart (which involved stretching her spine) and use that stored energy to execute a turn—which she did, painlessly. And when MIT’s fencing coach noticed a problem in the way his fencers were lunging, he assumed it was because their shoulders were tired. But Namburi’s measurements showed the problem was that the athletes were relying too much on their back muscles instead of their cores, a finding that changed the coach’s approach to teaching lunge technique.

Right now, Namburi is absorbed in trying to understand the intricacies of human movement. But down the road, he believes, his research could help older people avoid falls, workers perform their jobs more safely, and patients with movement disorders like Parkinson’s improve their mobility.

And once he understands the biophysics of artful movement, he hopes to explore the neuroscience behind it using the same kinds of molecular tools he employed in Tye’s lab.

Namburi explains his change in focus by saying he chose the opportunity that felt right—and the one that made sense to him.

“I thought to myself, if I don’t continue on my path in neuroscience, there are other people who will take that path. But if I don’t do this new research on movement, no one else will pursue this,” he says.

“My friends kept telling me it was brave of me, but I said bravery requires choice, and I really didn’t see any other choice.”

Ann Guo ’98, MEng ’99

From computer science to career coaching

After earning two computer science degrees from MIT and a PhD from the University of Massachusetts, Guo realized that she liked the ideas in the field—particularly AI—but didn’t find her career fulfilling. “The day-to-day work wasn’t as enjoyable to me,” she says. “Still, I just gritted my teeth and did it. I think, like other overachievers, I had gotten into something and I just didn’t want to quit.”

But after several years working as a product manager for a software company, as an online marketer, and as a recruiter for an algorithmic trading company, she realized that what she really enjoyed was advising employees and acquaintances on how to make career choices. Then, after organizing a panel on switching careers for the MIT Club of Boston more than a decade ago, she decided to make a switch herself. “I was on a high for the next week after helping other people feel like they’re not a loony bird to think about career change,” she recalls. “My husband said, ‘Whatever you did there, you need to do more of.’”

Today, she runs her own company, Passion Analytics, doing executive coaching and working with academics and others who are thinking about changing career paths. Her client list has included an MIT graduate who went from being a manager at a major satellite communications company to joining a startup where he could once again flex his technology muscles, and a statistics PhD whom she helped get a foothold working for Major League Baseball teams.

Although the day-to-day work wasn’t enjoyable, “I just gritted my teeth and did it. I think, like other overachievers, I had gotten into something and I just didn’t want to quit.”

The same technologies that have reshaped the economy—social media, cheaper computing power, 3D printing—have also made changing careers more possible than ever before, Guo says.

Not only can people do many jobs from home, she says, but it’s easier to go into business on your own. Those who choose that route can hire specialized help with things like marketing and design, and they can take advantage of maker spaces to create prototypes of their products. And working for yourself, she adds, means you don’t need to make as much money to achieve a comfortable lifestyle as you would if you had to hire a staff.

She says her coaching business got a boost during the pandemic: “When people’s mortality was in question, there was a lot of thinking about whether I’m in the right place and do I really want to keep doing this.”

But Guo can only work with 10 to 12 would-be career changers at a time, and she wanted to be able to help more people. So she drew on her computer science background to create an AI-powered chatbot called PAT (short for Passion Analyst), which she calls the world’s first artificially intelligent coach. In 2018 she started, as she puts it, downloading her brain into the chatbot in the form of a decision tree, making it possible for people to explore their career values with the automated assistant. She continues to glean insights from everyone PAT talks to.

“It’s a chatbot that attempts to provide some career design education in bite-size chunks,” she says. “It’s more to help people who don’t have the resources to do one-on-one coaching, and so far, more than a hundred people have used it.”

Isa Watson, MBA ’13

From pharmaceutical research to Wall Street to app development

Isa Watson started interning at an organic chemistry research lab at the University of North Carolina before she got out of high school. Then, as she earned her bachelor’s in chemistry and math at Hampton University and her master’s in pharmacology at Cornell University, she worked at Pfizer as a chemist and data scientist, specializing in metabolic diseases. But she found working in a lab “a little isolating,” she says, “because anything I did or touched wouldn’t touch another person for a decade or so.”

To make a more immediate impact in the world, she decided to go to the Sloan School at MIT to combine her technical and business interests. Although she planned to become a business development executive in biotech or pharma, she was recruited by several Wall Street firms as graduation approached. She joined J.P. Morgan, ultimately becoming a vice president of strategy as she worked in New York and Hong Kong on projects to reimagine small businesses and to create retirement planning tools for the Asian market.

Through all these career permutations, she realized that what she really enjoyed most was working with other people. She was also keenly aware that people her age and younger were losing the ability to form intimate friendships. “When you think of kids who grew up on social media, their friendship development habits just aren’t there,” she says. “So I thought, how can you take those technology models and help them build real friendships?”

That question led Watson to develop an app designed to help people move beyond the superficial friendships, posturing, and negative self-comparisons that are common on today’s social media platforms.

Called Squad, the app encourages users to build closer, more meaningful relationships with a core group of friends, using such tools as status updates, voice messages, and phone calls enhanced with emojis and previews of what the caller wants to talk about. As users describe it, Squad means “no flex, no stress—just my friends every day.” Originally targeted to Gen Z, the app is now expanding to sports fan bases and is slated to roll out to a handful of NBA cities this fall.

The app is new but already has thousands of users in the New York City area, and Watson says she has raised $6 million in initial investments. She has also written a book on how to avoid the negative impacts of social media, called Life Beyond Likes: Logging Off Your Screen and Into Your Life (2023).

Like Guo, Watson thinks Millennials and Gen Z workers will change careers more readily than previous generations because they think of themselves more as having certain skills than as being in a particular profession.

“No one wants to stay in a company for 30 years to get a plaque,” she says. “Millennials and Gen Zers follow our passions and don’t let our academic degrees box us in.”

Joylette Portlock ’99

From biology to sustainability (with many stops in between)

In the 24 years since she got her MIT degree in biology with an anthropology minor, Joylette Portlock ’99 has worked as a staff assistant to then-senator Joe Biden, a genetics researcher, a program coordinator at a science museum, associate director of science and research at a natural history museum, and head of her own media nonprofit specializing in climate change. Along the way, she earned a PhD in genetics from Stanford. Today she serves as executive director of Sustainable Pittsburgh, a nonprofit that helps organizations meet sustainability goals, works on environmental policy initiatives, and tries to reduce economic inequality.

MIT was a great place to begin her multifaceted career journey, she says, because it has so many experts to learn from.

In addition to being fascinated by science, Portlock has always been very interested in how social institutions work. So before starting her PhD at Stanford, she worked in Biden’s office for a year to see up close how the political system functioned. Among other things, it taught her that one of the biggest challenges citizens face is their lack of awareness about government programs and how to access them.

At Stanford, she worked in the lab of Michele Calos, studying a gene therapy system that used viruses known as bacteriophages to deliver genetic material into mammalian cells.

But like Watson, Portlock yearned for public engagement. That led her to jobs at the Tech Interactive museum in San Jose and the Exploratorium in San Francisco, and eventually to a position as associate director at Pittsburgh’s Carnegie Museum of Natural History, known for its research in paleontology and evolutionary biology.

In 2018, she took on the job of leading Sustainable Pittsburgh, where one of her main objectives has been promoting regional decarbonization—a tough challenge in an area that was once dominated by the steel industry.

“It’s a big focus for us right now,” she says. “We’re asking, how can we make as much progress as possible while simultaneously creating as many economic development opportunities as possible?”

A common thread in all of her work has been her ongoing effort to make sure that important information—whether it’s scientific, technical, or merely complex—is accessible and useful to anyone who needs it.

“I often say to people that a lot of the work I do now, at the intersection between environmental stewardship and development, involves systems thinking, which I learned in my technical training as a biologist,” she says. “It’s not such a reach to go from how all the systems in an organism are interrelated to being able to grapple with these really complex problems regarding sustainability.

“I think the more people who have technical training and the ability to translate scientific material to the public—well, that’s a pretty useful space to be in.”

The opportunity to move forward

After years in the top ranks of professional poker players, Andy Bloch says he has learned a lot of life lessons that could apply to any major decision, including making a career change.

One of the biggest is not to be held captive by your past choices. Economists call the natural human reluctance to change course the “sunk-cost fallacy.” Poker pros call it being “pot stuck.”

Players who don’t learn this lesson well, Bloch says, “feel they’ve put so much money in the pot they have to call the last bet even though they know they don’t have a great chance—or any chance—of winning.”

In poker and in life, Bloch says, “what you have to realize is the money that’s in the pot is no longer yours. The money and time you spent are no longer yours, and the only thing that matters is the opportunity you have moving forward. You have to concentrate on the opportunity you have at that point in time.”

Contemplating a career change?

Career coach Ann Guo ’98, MEng ’99, offers advice to those considering a new path.

- Sure, you could continue advancing in a shrinking field that feels comfortable. But you might be happier working in a new environment with more opportunities.

- Worried that if you specialize in certain skills, you’ll pigeonhole yourself? One way to hedge this risk is to get better at pivoting.

- Look for mutually beneficial opportunities when you network by asking what information or services you can provide to others now or in the future.

- If you’re considering entrepreneurship, ask yourself whether you can be a “solopreneur” instead of building a team. By outsourcing services such as R&D, production, and IT, you can contain expenses and focus on what you’re good at.