China is still finding ways to skirt US export controls on Nvidia chips, Reuters reported.

A Reuters review of publicly available tender documents showed that last year dozens of entities—including “Chinese military bodies, state-run artificial intelligence research institutes, and universities”—managed to buy “small batches” of restricted Nvidia chips.

The US has been attempting to block China from accessing advanced chips needed to achieve AI breakthroughs and advance modern military technologies since September 2022, citing national security risks.

Reuters’ report shows just how unsuccessful the US effort has been to completely cut off China, despite repeated US attempts to expand export controls and close any loopholes discovered over the past year.

China’s current suppliers remain “largely unknown,” but Reuters confirmed that “neither Nvidia” nor its approved retailers counted “among the suppliers identified.”

An Nvidia spokesperson told Reuters that the company “complies with all applicable export control laws and requires its customers to do the same.”

“If we learn that a customer has made an unlawful resale to third parties, we’ll take immediate and appropriate action,” Nvidia’s spokesperson said.

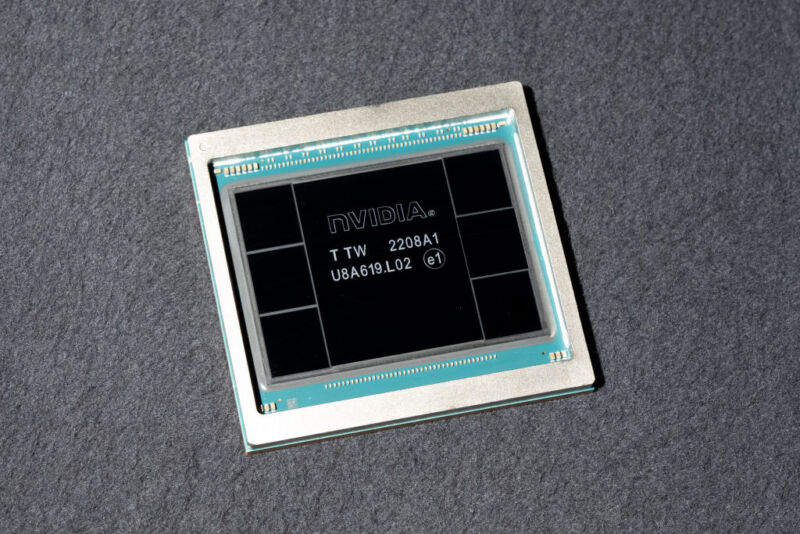

It’s also still unclear how suppliers are procuring the chips, which include Nvidia’s most powerful chips, the A100 and H100, in addition to slower modified chips developed just for the Chinese market, the A800 and H800. The former chips were among the first banned, while the US only began restricting the latter chips last October.

Among military and government groups purchasing chips were two top universities that the US Department of Commerce has linked to China’s principal military force, the People’s Liberation Army, and labeled as a threat to national security. Last May, the Harbin Institute of Technology purchased six Nvidia A100 chips to “train a deep-learning model,” and in December 2022, the University of Electronic Science and Technology of China purchased one A100 for purposes so far unknown, Reuters reported.

Other entities purchasing chips include Tsinghua University—which is seemingly gaining the most access, purchasing “some 80 A100 chips since the 2022 ban”—as well as Chongqing University, Shandong Chengxiang Electronic Technology, and “one unnamed People’s Liberation Army entity based in the city of Wuxi, Jiangsu province.”

In total, Reuters reviewed more than 100 tenders showing state entities purchasing A100 chips and dozens of tenders documenting A800 purchases. Purchases include “brand new” chips and have been made as recently as this month.

Most of the chips purchased by Chinese entities are being used for AI, Reuters reported. None of the purchasers or suppliers provided comments in Reuters’ report.

Nvidia’s highly sought-after chips are graphic processing units capable of crunching large amounts of data at the high speeds needed to fuel AI systems. For now, these chips remain irreplaceable to Chinese firms hoping to compete globally, as well as nationally, with China’s dominant technology players, such as Huawei, Reuters suggested.

While the “small batches” of chips found indicate that China could still be accessing enough Nvidia chips to enhance “existing AI models,” Reuters pointed out that US curbs are effectively stopping China from bulk-ordering chips at quantities needed to develop new AI systems. Running a “model similar to OpenAI’s GPT would require more than 30,000 Nvidia A100 cards,” research firm TrendForce reported last March.

For China, which has firmly opposed the US export controls every step of the way, these curbs remain a persistent problem despite maintaining access through the burgeoning black market. On Monday, a Bloomberg report flagged the “steepest drop” in the value of China chip imports ever recorded, falling by more than 15 percent.

China’s black market for AI chips

One question that the US still must confront is whether it’s possible to block China from accessing advanced chips without other allied nations joining the effort by lobbing their own export controls.

In October 2022, a senior US official warned that without more cooperation, US curbs will “lose effectiveness over time.” A former top Commerce Department official, Kevin Wolf, told The Wall Street Journal last year that it’s “insanely difficult to enforce” US export controls on transactions overseas.

Part of the problem, sources told Reuters in October 2023, is that overseas subsidiaries were “easily” smuggling restricted chips into China or else providing remote access to chips to China-based employees.

On top of that activity, a black market for chips developed quickly, selling “excess stock that finds its way to the market after Nvidia ships large quantities to big US firms” or else chips imported “through companies locally incorporated in places such as India, Taiwan, and Singapore,” Reuters reported.

The US has maintained that its plan is not to ensure that China has absolutely no access but to limit access enough to keep China from getting ahead. But Nvidia CEO Jensen Huang has warned that curbs could have the opposite effect. While China finds ways to skirt the bans and acquire chips to “inspire” advancements, US companies that have been impacted by export controls restricting sales in China could lose so much revenue that they fall behind competitively, Huang predicted.

One example likely worrying to Huang and other tech firms came last November, when Huawei shocked the US government by unveiling a cutting-edge chip that seemed to prove US sanctions weren’t doing much to limit China’s ability to compete.