Registrars can now block people from registering tens of thousands of domain names that look like, are spelling variations of, or otherwise infringe on brand names.

GlobalBlock, a solution already in use by leading registrars like GoDaddy Corporate Domains, 101domain, and MarkMonitor lets businesses pay a subscription fee to reserve a part of the domain space, as a means to protect their trademark. But, is there more to this than meets the eye?

Blocks similar domains, even homoglyphs

Traditionally, companies and brands have had to manually register multiple domain names with different extensions (TLDs) or variations of their spellings to both protect their trademark and prevent malicious usage.

As an example, owners of apple.com would be (and are) wise to also reserve apple.co.uk, apple.in, among others to prevent another business from using the name, or worse, having a threat actor misuse some ‘apple’ domains for running phishing and scam operations.

Furthermore, domain typosquatting attacks where threat actors set up domains that are slightly misspelled variations of legitimate services to direct visitors to their malicious websites aren’t unheard of. For example, should a user intending to visit Google mistakenly type gooogle.com in their address bar, they could potentially fall victim to a typosquatting attack. Thankfully, Google has already reserved this particular example.

But where does it stop?

A domain name can consist of alphabets, numbers, and hyphens—from varying character sets, further leading to a possibility of homograph attacks, as we have previously seen.

Homograph attacks consist of attackers registering lookalike domains with homoglyphs: characters that look the same to the naked eye but are, in reality, distinct, due to different character sets and encoding.

For example, the Cyrillic letter ‘а’ looks exactly like the Latin alphabet ‘a’ but the two are vastly different. Copying-pasting аbc.com in your browser (try it) would not lead you to the real abc.com, but the Cyrillic text will first change to its ASCII-equivalent (punycode) version, sending you to a different domain.

Even by simply using the Latin alphabet, threat actors can and have crafted phishing emails directing readers to illicit domains with confusingly similar characters, such as Iimited.com (starting with an ‘i’) as opposed to limited.com, or e1onmusk.website (‘1’ instead of an ‘l’).

This existing set of problems is what GlobalBlock aims to address.

GlobalBlock, an initiative of Brand Safety Alliance (a GoDaddy subsidiary), allows brands to pay a subscription fee to their registrar, and select “labels” or terms they would want to block others from registering.

A user intending to register a new domain matching one or more labels, or its permutations, will not be able to proceed with the registration because of GlobalBlock in use by the registrar.

An FAQ on the website explains what kinds of “labels” are available and what each of these means.

BleepingComputer understands that by tomorrow, February 29th, GlobalBlock will be “generally available” across leading registrars.

Domains we could block: ‘70,094’

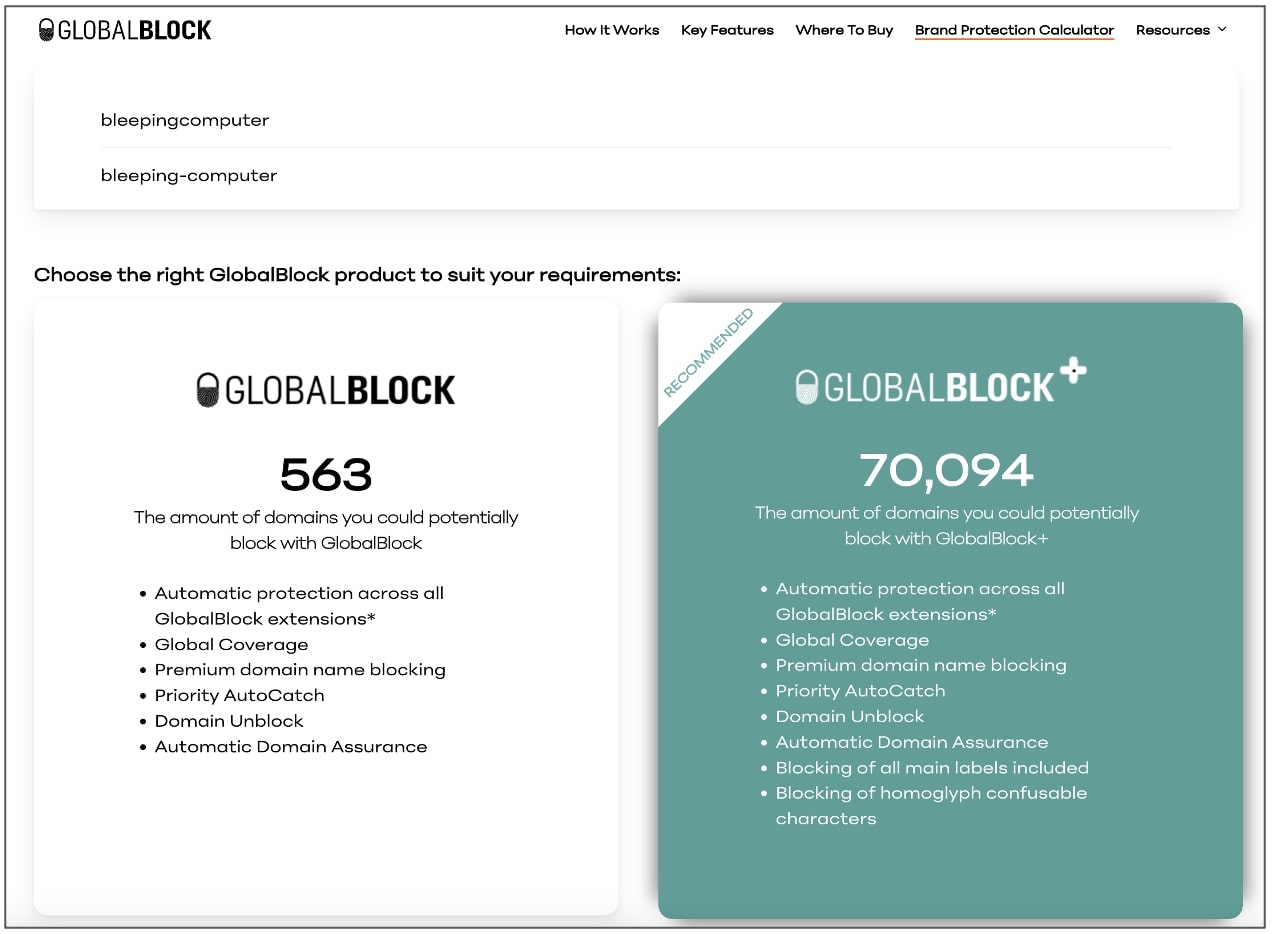

While the basic plan lets subscribers block specific domain names that read like their trademark across some 563 extensions (TLDs), the “plus” version takes a huge leap forward.

The extensive GlobalBlock+ plan can potentially restrict tens of thousands of domain names from being registered, including those with confusable homoglyph characters, and a ‘main label’—that is any domain containing a particular term itself or its variations.

For example, in a test we used the service’s “brand protection calculator” to see how many domains containing a variation of “Bleeping Computer” could we prevent others from squatting, and the result was an alarming 70,094, should we subscribe to GlobalBlock+.

At this time, the service protects both unregistered and registered trademarks, including geographical indicators, marks protected by statute or treaty, company or organization names, and celebrity names.

Furthermore, the service offers a priority “AutoCatch” feature, akin to drop-catching a domain, which means as soon as a previously registered domain that reads similar to a brand name expires or otherwise becomes available, GlobalBlock will snatch it for their paying customer.

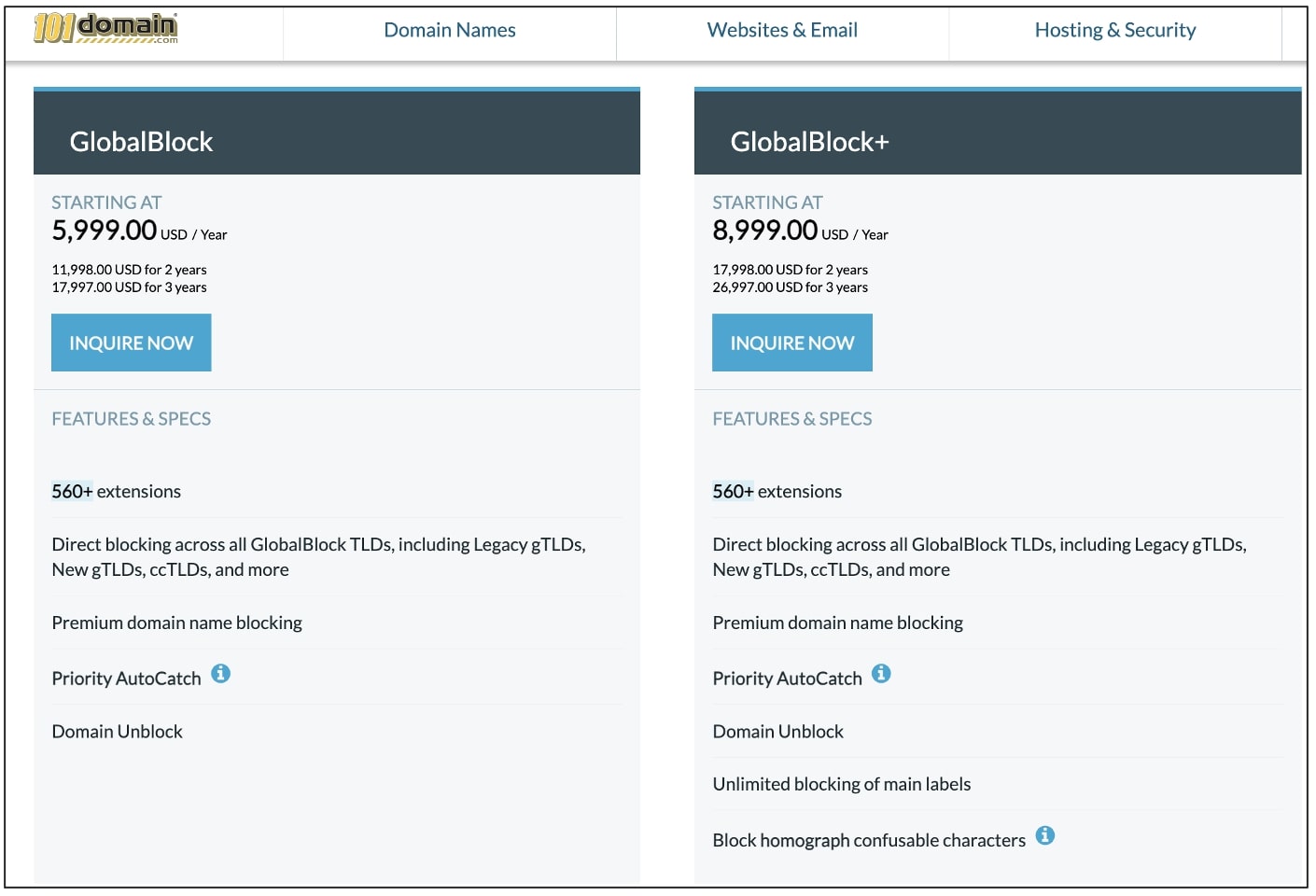

Mind you, the service doesn’t come cheap either.

Prices for the solution at registrar 101domain, for example, start at an annual $5,999 fee for a basic plan “to block over 560 extensions.” The rigorous, “plus” blocking starts at $8,999 a year.

Perhaps for big corporations, the pricing structure may prove to be much more cost-effective and efficient than manually having to squat hundreds to thousands of domain names, manage them, and pay hefty annual renewal fees for each.

Free speech concerns

No doubt, a solution like GlobalBlock, when implemented by leading registrars can save brands the hassle of registering every domain that has its echoes. But, I couldn’t help but wonder if an automated solution this vast could end up providing an undue advantage to companies in hoarding up the domain space.

Should a company or celebrity reserve their name and use “unlimited blocking of main labels,” this would effectively prevent registration of a domain with that term.

In other words, could a famous JohnSmith now block you from registering JohnSmithSucks.com, or your next-door ‘iPhone Repair Shop’ be compelled to find a domain name that is free from a trademark?

At this time, it isn’t clear if GlobalBlock would only restrict domain registrations that exactly contain a brand name (and its spelling variations), or will its scope expand to cover domain names containing any part of a brand name along with other terms (i.e. walmart.com vs. walmartsucks.com).

More interestingly though, trademark protection generally applies to goods and services in a particular class and that too in specific jurisdictions thereby complicating matters.

It isn’t hard to imagine a hypothetical Apple Clothing company that has nothing to do with the tech giant, being interested in purchasing a domain name.

Ironically, GlobalBlock itself acknowledges conflicting cases where it may be possible for a party to block someone else’s trademark (in its FAQ, under “Can someone else block my trademark or rights?”).

It may be possible “for multiple parties to hold matching verified rights, e.g., two or more identical marks registered by separate trademark owners that cover distinct goods or services, or that are registered in different jurisdictions,” states the service.

In such instances, GlobalBlock’s current answer states that “any label that is blocked by more than one rights holder cannot be unblocked without the consent of all applicable rights holders.”

We also reached out to the Electronic Frontier Foundation (EFF) to explore potential concerns with a solution like GlobalBlock.

“The fundamental problem with services like this is that they suppress far more domains than merely those that would infringe trademark. Domain names are themselves a form of speech that we don’t want to see constrained by overzealous attempts at brand enforcement,” Kit Walsh, senior staff attorney at EFF told BleepingComputer in a statement.

Walsh, who also serves as EFF’s Director of Artificial Intelligence & Access to Knowledge Legal Projects, explained that trademarks based on generic terms when combined with a tool like this, could interfere with free speech.

“Many trademarks are common words, like ‘Apple,’ surnames, like ‘Ford,’ or drawn from preexisting culture, like ‘Nike.’ Even if a trademark is a unique word, people have a right to talk about brands, products, and aspects of culture.”

“To do otherwise silences critical speech, parody, fan works, or even unrelated but similar business names.”

Giving variable examples like ‘Boycott EFF,’ ‘Not The EFF,’ and ‘EFF Plumbers,’ Walsh stressed that creators of such websites should have the right to get and keep their sites if they existed, much like the historical “walmartsucks.com.”

Similarly, if a service was able to block any domain with “EFF” in it, says Walsh, it would eliminate a lot of words from the English language, like Effect, Effort, Effervescent, and so on.

The attorney further told BleepingComputer that these problems multiply when we consider that “English is far from the only language used on the internet.”

“Common words in our language would impede expression in other languages, and vice versa. Some Ikea furniture names are quite similar to Thai slang for sex acts, for instance, Barf is a well-known Iranian soap brand.”

Walsh referred to Ford’s marketing fiasco from the seventies when the company’s ‘Pinto’ car models had to be renamed to ‘Corcel’ in the Brazilian market for the former is slang for certain genitalia.

“‘Protecting brands’ isn’t the end goal of trademark; the goal is preventing consumers from being confused about who’s responsible for the goods and services they buy. Blocking speech that wouldn’t be confusing anyway is simply a net loss for the public interest.”

The expert advises that the Uniform Dispute Resolution Policy (UDRP) that registrars must follow, already empowers trademark owners with powerful tools to claim domain names that are likely to create confusion.

“Automated systems like these should not circumvent what protections exist for good-faith use of domain names that happen to be similar but have legitimate purposes.”