During the first summer of COVID, many people took to the road, filling up campgrounds like those surrounding the mountains and deserts near where I live in New Mexico. My family stayed put, but we were busy embarking on a journey of our own: Moving off the grid and taking on the responsibility of supplying our own electricity, heat and water using solar panels, wood, propane and rain catchment.

Over a series of articles and videos here at CNET, I’m going to share this “living off the grid” journey with you, detailing how we manage without being connected to any public infrastructure.

Though I’ve made plenty of mistakes and learned lessons over the past three years, the adventure has also slashed our living cost and empowered me with a greater understanding and fascination around how both natural and built systems work and interact.

In short, I feel like a smarter, more useful human after moving off the grid.

The ultimate pandemic project

In 2020, my family was living in a typical three-bedroom house at the end of a cul-de-sac in a small town in northern New Mexico.

One day early into COVID lockdown, my wife finished wiping down some groceries with sanitizing wipes, turned to me, and said:

“This is bullshit. The apocalypse is actually here, and we’re scared of our own snacks.”

Glass bottles set into the walls of the house bring light in from the outside.

My wife has long been a bit of a closet prepper, with dreams of retreating to an isolated homestead and living out our days in some quiet, natural setting. COVID seemed to be that moment — yet we were trapped on a dead-end street in a neighborhood behind the county jail instead.

So we did the only thing anyone could at that moment: we went online. My wife found an intriguing listing on Craigslist, a small house made of straw bales and stucco located in a small, quirky off-grid community 20 minutes outside of town.

The house itself is built in a funky southwestern style and also takes some inspiration from the sustainable construction concept known as Earthships, including glass bottles built into the walls to allow extra light and serve as a sort of permanent recycling. The basic structure appealed to some moves we had been making towards downsizing and minimizing our lifestyle: just one cozy bedroom, a few common areas, a bathroom, and a loft with sweet views for our teenager.

There was one pretty big catch: While the structure was finished, there was no solar system, internal electrical wiring or plumbing installed.

Forget baking sourdough. This was going to be the ultimate pandemic project.

Solar energy is the first source of energy off the grid.

My wife suggested calling professionals, but during lockdown wait lists were long, if someone was even willing to drive out to our location. Besides, I argued, installing it ourselves meant we could better know how to fix it ourselves.

In my past, I had accumulated some relevant DIY experience installing solar systems and plumbing on RVs, but this was going to be a whole new level.

I dove into YouTube, talked to friends and relatives with experience, and studied building codes to figure out the right way to do things without burning our new house down or flooding it. There were still a few close calls with that — it’s a really bad idea to try and run a vacuum cleaner off the car battery you’re using for a back-up source of power during construction, for example.

Slowly, much slower than I ever dreamed, it all came together. Definitely no more car batteries in the house today. We’re all photovoltaic panels and lithium-ion now.

Water and power direct from the sky

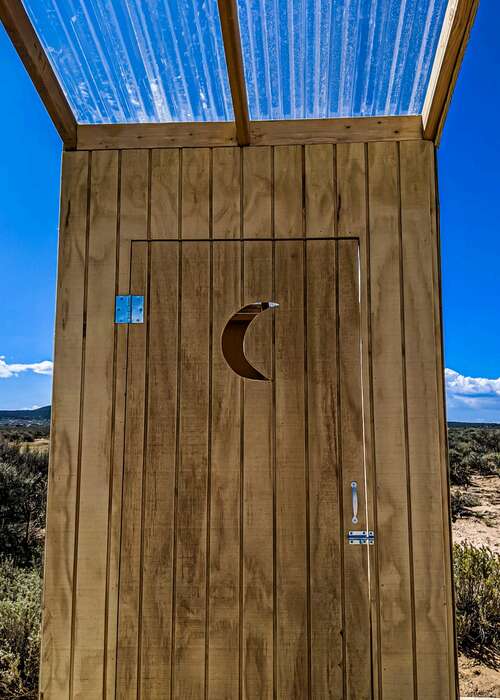

Today our water comes primarily from the sky via the roof and gutters feeding two 1,600-gallon tanks behind our house. During dry spells water can be delivered by tanker trucks, or 200 gallons at a time from a community well using my own truck for a fraction of the cost. In good years, summer monsoons fill our tanks with enough water to last until the end of winter. In the spring, a stray rain storm saves both time and money that would otherwise be spent hauling water. To conserve, we’ve swapped out our flushing water toilet for a compost toilet along with an outhouse for a second bathroom. I’ll spare the details.

A no-frills, reliable second bathroom.

We’re also obsessive about recycling water. The “gray” water from our sinks and bathtubs flows outside into three large trenches buried under two feet of mulch and soil where we grow healthy gardens, fruit trees and berry patches that would otherwise be impossible in the harsh climate here. We also catch a portion of our dish and shower water in small buckets and haul it outside to water other flowers, herbs, vines and trees on other parts of the property. We’re quickly establishing our own little microclimate.

Living in the arid west, conserving water has always been a priority, but we’re also stingy with electricity. This might seem counterintuitive when our solar panels make it clean and free, but we’re still aiming for a minimalist lifestyle. We weren’t willing to fill our yard with solar panels or take up valuable storage space with batteries. So for now we also conserve electrons, especially in the winter months when our solar batteries are being drained more hours out of the day than they charge.

Recycling water makes a garden in the desert possible.

A little device called a Kill-a-watt has become one of my best friends; it reveals precisely how much power any appliance is consuming. I can tell you how much energy every light or gadget in my house uses. I know how much wattage my laptop is using when its fan is running or when it’s plugged in and in sleep mode.

For now we’re also forgoing some luxuries that we’ve discovered take up more power and space than they’re worth. Farewell, noble clothes dryer, Instapot and Vitamix.

So why are we consuming less water and electricity when we’ve reduced our footprint to a fraction of what it was and we have a surplus of energy most days? I think it goes back to becoming more energy independent by taking responsibility for even the essentials. The flip side of responsibility is accountability, so maybe I obsess a bit over how we consume each drop of water or electron. But I think it’s also true that having a closer relationship with both simply leads to respecting and appreciating them more and not taking them for granted.

It’s a newfound respect that runs deep. In fact, I think our solar energy system is one of the most magical pieces of modern technological sorcery. For all the details on why, and some practical tips I’ve learned for powering an off-grid life, check out the next installment of this series.