In the past few months, we’ve seen a deepfake robocall of Joe Biden encouraging New Hampshire voters to “save your vote for the November election” and a fake endorsement of Donald Trump from Taylor Swift. It’s clear that 2024 will mark the first “AI election” in United States history.

With many advocates calling for safeguards against AI’s potential harms to our democracy, Meta (the parent company of Facebook and Instagram) proudly announced last month that it will label AI-generated content that was created using the most popular generative AI tools. The company said it’s “building industry-leading tools that can identify invisible markers at scale—specifically, the ‘AI generated’ information in the C2PA and IPTC technical standards.”

Unfortunately, social media companies will not solve the problem of deepfakes on social media this year with this approach. Indeed, this new effort will do very little to tackle the problem of AI-generated material polluting the election environment.

The most obvious weakness is that Meta’s system will only work if the bad actors creating deepfakes use tools that already put watermarks—that is, hidden or visible information about the origin of digital content—into their images. Unsecured “open-source” generative AI tools mostly don’t produce watermarks at all. (We use the term unsecured and put “open-source” in quotes to denote that many such tools don’t meet traditional definitions of open-source software, but still pose a threat because their underlying code or model weights have been made publicly available.) If new versions of these unsecured tools are released that do contain watermarks, the old tools will still be available and able to produce watermark-free content, including personalized and highly persuasive disinformation and nonconsensual deepfake pornography.

We are also concerned that bad actors can easily circumvent Meta’s labeling regimen even if they are using the AI tools that Meta says will be covered, which include products from Google, OpenAI, Microsoft, Adobe, Midjourney, and Shutterstock. Given that it takes about two seconds to remove a watermark from an image produced using the current C2PA watermarking standard that these companies have implemented, Meta’s promise to label AI-generated images falls flat.

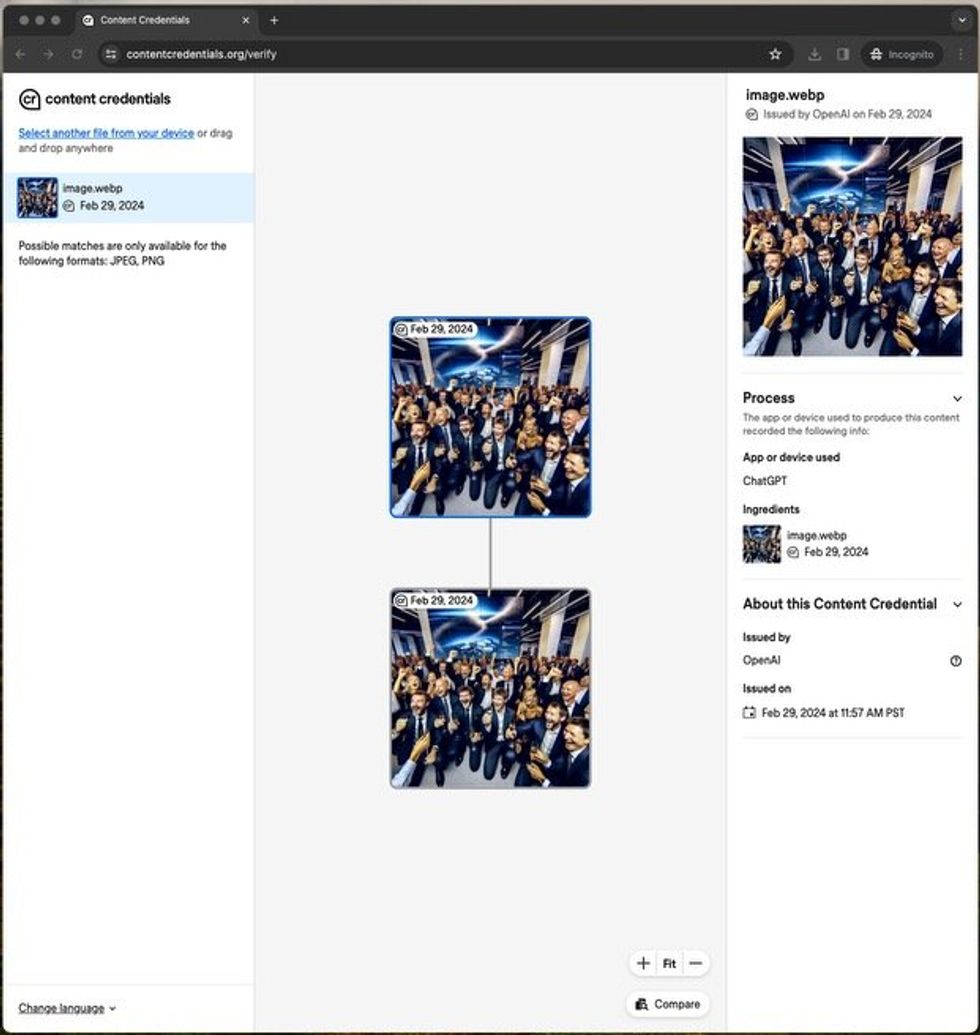

When the authors uploaded an image they’d generated to a website that checks for watermarks, the site correctly stated that it was a synthetic image generated by an OpenAI tool. IEEE Spectrum

When the authors uploaded an image they’d generated to a website that checks for watermarks, the site correctly stated that it was a synthetic image generated by an OpenAI tool. IEEE Spectrum

We know this because we were able to easily remove the watermarks Meta claims it will detect—and neither of us is an engineer. Nor did we have to write a single line of code or install any software.

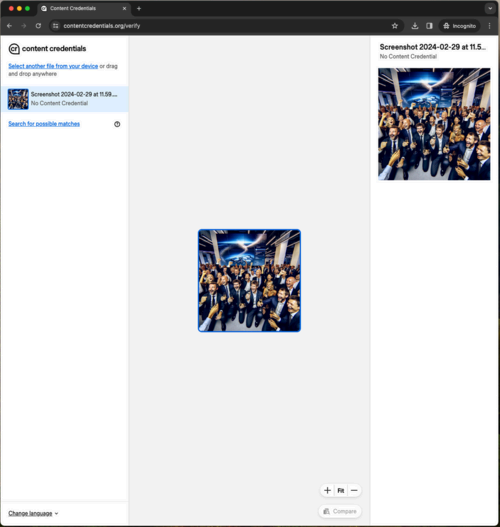

First, we generated an image with OpenAI’s DALL-E 3. Then, to see if the watermark worked, we uploaded the image to the C2PA content credentials verification website. A simple and elegant interface showed us that this image was indeed made with OpenAI’s DALL-E 3. How did we then remove the watermark? By taking a screenshot. When we uploaded the screenshot to the same verification website, the verification site found no evidence that the image had been generated by AI. The same process worked when we made an image with Meta’s AI image generator and took a screenshot of it.

However, when the authors took a screenshot of the image and uploaded that screenshot to the same verification site, the site found no watermark and therefore no evidence that the image was AI-generated. IEEE Spectrum

However, when the authors took a screenshot of the image and uploaded that screenshot to the same verification site, the site found no watermark and therefore no evidence that the image was AI-generated. IEEE Spectrum

Is there a better way to identify AI-generated content?

Meta’s announcement states that it’s “working hard to develop classifiers that can help … to automatically detect AI-generated content, even if the content lacks invisible markers.” It’s nice that the company is working on it, but until it succeeds and shares this technology with the entire industry, we will be stuck wondering whether anything we see or hear online is real.

For a more immediate solution, the industry could adopt maximally indelible watermarks—meaning watermarks that are as difficult to remove as possible.

Today’s imperfect watermarks typically attach information to a file in the form of metadata. For maximally indelible watermarks to offer an improvement, they need to hide information imperceptibly in the actual pixels of images, the waveforms of audio (Google Deepmind claims to have done this with their proprietary SynthID watermark) or through slightly modified word frequency patterns in AI-generated text. We use the term “maximally” to acknowledge that there may never be a perfectly indelible watermark. This is not a problem just with watermarks though. The celebrated security expert Bruce Schneier notes that “computer security is not a solvable problem…. Security has always been an arms race, and always will be.”

In metaphorical terms, it’s instructive to consider automobile safety. No car manufacturer has ever produced a car that cannot crash. Yet that hasn’t stopped regulators from implementing comprehensive safety standards that require seatbelts, airbags, and backup cameras on cars. If we waited for safety technologies to be perfected before requiring implementation of the best available options, we would be much worse off in many domains.

There’s increasing political momentum to tackle deepfakes. Fifteen of the biggest AI companies—including almost every one mentioned in this article—signed on to the White House Voluntary AI Commitments last year, which included pledges to “develop robust mechanisms, including provenance and/or watermarking systems for audio or visual content” and to “develop tools or APIs to determine if a particular piece of content was created with their system.” Unfortunately, the White House did not set any timeline for the voluntary commitments.

Then, in October, the White House, in its AI Executive Order, defined AI watermarking as “the act of embedding information, which is typically difficult to remove, into outputs created by AI—including into outputs such as photos, videos, audio clips, or text—for the purposes of verifying the authenticity of the output or the identity or characteristics of its provenance, modifications, or conveyance.”

Next, at the Munich Security Conference on 16 February, a group of 20 tech companies (half of which had previously signed the voluntary commitments) signed onto a new “Tech Accord to Combat Deceptive Use of AI in 2024 Elections.” Without making any concrete commitments or providing any timelines, the accord offers a vague intention to implement some form of watermarking or content provenance efforts. Although a standard is not specified, the accord lists both C2PA and SynthID as examples of technologies that could be adopted.

Could regulations help?

We’ve seen examples of robust pushback against deepfakes. Following the AI-generated Biden robocalls, the New Hampshire Department of Justice launched an investigation in coordination with state and federal partners, including a bipartisan task force made up of all 50 state attorneys general and the Federal Communications Commission. Meanwhile, in early February the FCC clarified that calls using voice-generation AI will be considered artificial and subject to restrictions under existing laws regulating robocalls.

Unfortunately, we don’t have laws to force action by either AI developers or social media companies. Congress and the states should mandate that all generative AI products embed maximally indelible watermarks in their image, audio, video, and text content using state-of-the-art technology. They should also address risks from unsecured “open-source” systems that can either have their watermarking functionality disabled or be used to remove watermarks from other content. Furthermore, any company that makes a generative AI tool should be encouraged to release a detector that can identify, with the highest accuracy possible, any content it produces. This proposal shouldn’t be controversial, as its rough outlines have already been agreed to by the signers of the voluntary commitments and the recent elections accord.

Standards organizations like C2PA, the National Institute of Standards and Technology, and the International Organization for Standardization should also move faster to build consensus and release standards for maximally indelible watermarks and content labeling in preparation for laws requiring these technologies. Google, as C2PA’s newest steering committee member, should also quickly move to open up its seemingly best-in-class SynthID watermarking technology to all members for testing.

Misinformation and voter deception are nothing new in elections. But AI is accelerating existing threats to our already fragile democracy. Congress must also consider what steps it can take to protect our elections more generally from those who are seeking to undermine them. That should include some basic steps, such as passing the Deceptive Practices and Voter Intimidation Act, which would make it illegal to knowingly lie to voters about the time, place, and manner of elections with the intent of preventing them from voting in the period before a federal election.

Congress has been woefully slow to take up comprehensive democracy reform in the face of recent shocks. The potential amplification of these shocks through abuse of AI ought to be enough to finally get lawmakers to act.

From Your Site Articles

Related Articles Around the Web