Public domain

When Leonardo da Vinci was creating his masterpiece, the Mona Lisa, he may have experimented with lead oxide in his base layer, resulting in trace amounts of a compound called plumbonacrite. It forms when lead oxides combine with oil, a common mixture to help paint dry, used by later artists like Rembrandt. But the presence of plumbonacrite in the Mona Lisa is the first time the compound has been detected in an Italian Renaissance painting, suggesting that da Vinci could have pioneered this technique, according to the authors of a recent paper published in the Journal of the American Chemical Society.

Fewer than 20 of da Vinci’s paintings have survived, and the Mona Lisa is by far the most famous, inspiring a 1950s hit song by Nat King Cole and featuring prominently in last year’s Glass Onion: a Knives Out Mystery, among other pop culture mentions. The painting is in remarkably good condition given its age, but art conservationists and da Vinci scholars alike are eager to learn as much as possible about the materials the Renaissance master used to create his works.

There have been some recent scientific investigations of da Vinci’s works, which revealed that he varied the materials used for his paintings, especially concerning the ground layers applied between the wooden panel surface and the subsequent paint layers. For instance, for his Virgin and Child with St. Anne (c. 1503–1519), he used a typical Italian Renaissance gesso for the ground layer, followed by a lead white priming layer. But for La Belle Ferronniere (c. 1495–1497), da Vinci used an oil-based ground layer made of white and red lead.

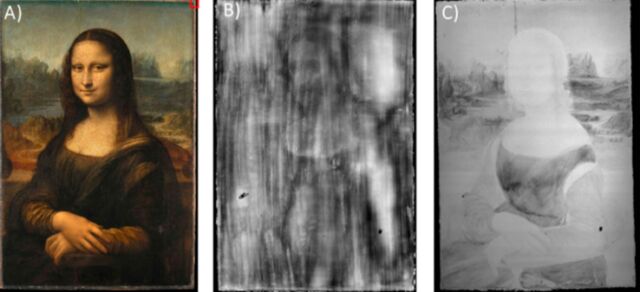

For his large wall painting, The Last Supper—his second most famous work—he used an oil-based lead white priming layer rather than the traditional fresco technique. As for the Mona Lisa, various X-ray analyses of the painting showed the presence of heavy elements within the poplar wood panel, which could mean that da Vinci used a lead-based pigment or an oil medium treated with lead during the grinding. The ground layer appears to be a single layer of lead white with no gesso.

V. Gonzalez et al., 2023

In other words, da Vinci was constantly experimenting with his artistic materials. “From 1485 to 1490, each known easel painting of Leonardo presents a different type of ground layer,” Victor Gonzalez of Universite Paris-Salcay and his co-authors wrote in their paper. “Their only common features are that they are oil-based and that they contain the lead white pigment called biacca by Leonardo in his writings.”

Gonzalez et al. decided to take a closer look at the Mona Lisa‘s ground layer with X-ray diffraction and infrared spectroscopy, analyzing a tiny microsample taken from a hidden corner of the painting back in 2007. They were surprised to find plumbonacrite in the mix in addition to lead white and oil since the compound has previously been detected only in later paintings. These include a painting fragment by Vincent van Gogh—likely due to the degradation of a red lead pigment as a result of exposure to light—and in the thick lead white impasto used by Rembrandt in several of his paintings, most notably The Night Watch.