J. Casana et al./US Geological Survey

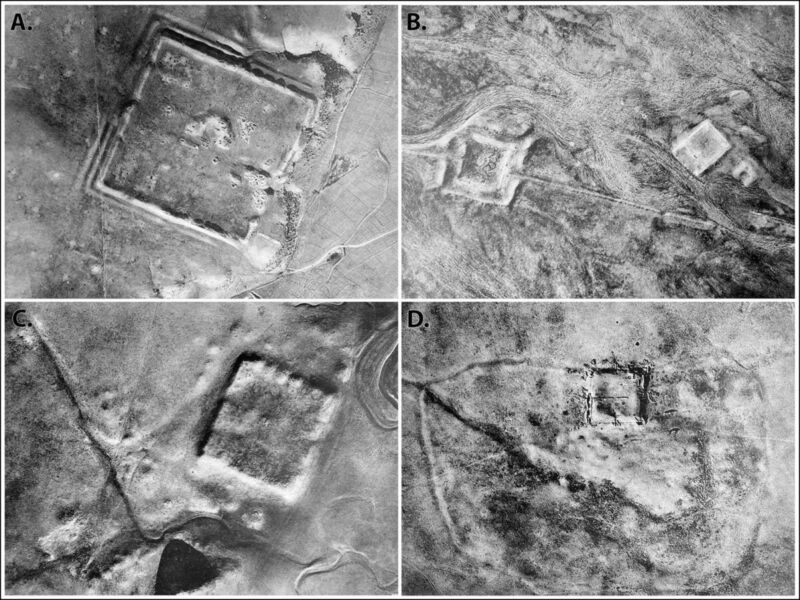

Back in the early days of aerial archaeology, a French Jesuit priest named Antoine Poidebard flew a biplane over the northern Fertile Crescent to conduct one of the first aerial surveys. He documented 116 ancient Roman forts spanning what is now western Syria to northwestern Iraq and concluded that they were constructed to secure the borders of the Roman Empire in that region.

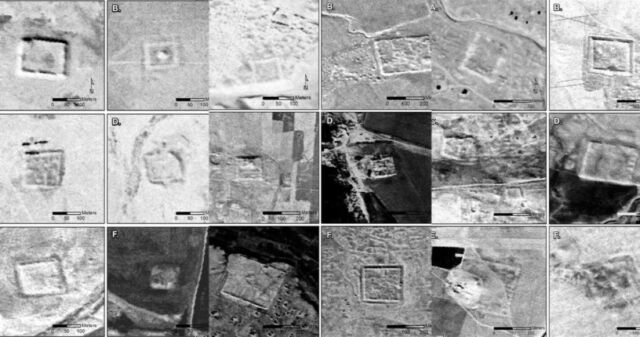

Now, anthropologists from Dartmouth have analyzed declassified spy satellite imagery dating from the Cold War, identifying 396 Roman forts, according to a recent paper published in the journal Antiquity. And they have come to a different conclusion about the site distribution: the forts were constructed along trade routes to ensure the safe passage of people and goods.

Poidebard is a fascinating historical figure. A former World War I pilot, he later became a priest and joined the French Levant forces, helping pioneer the use of aerial photography as an archaeological surveying tool to discover and record sites of interest. (Previously, hot air balloons, scaffolds, or attaching cameras to kites were the primary means of gaining aerial context.) For his mapping missions, Poidebard clocked thousands of hours flying over Syria, as well as Algeria and Tunisia along the Mediterranean coast. He published his catalog of ancient Roman forts in his 1934 book, The Trace of Rome in the Syrian Desert, including some of the largest and best-known sites, including Sura, Resafa, and Ain Sinu.

Poidebard’s map showed the fort sites roughly running in a north-south line along the eastern boundary of the Roman Empire. This corresponded with a road built under the emperor Diocletian (284–305 CE) known as the strata Diocletiana. Poidebard believed the forts were mostly constructed during the second and third centuries CE as a border wall to defend the eastern Roman provinces from invasions by Arab nomads or Persian armies. But later scholars argued that the forts were too far apart to function efficiently as a border wall, suggesting instead that they had been used to provide protection for military and commercial caravans in the region—or possibly to defend local populations from nomadic raids.

J. Casana et al./US Geological Survey

This latest study bolsters the latter hypothesis, with the authors attributing Poidebard’s original conclusions to discovery bias. “He flew his biplane over areas where he believed forts would most likely be located and found many of them, seemingly confirming his theory of their function in fortifying the Roman limes [border],” they wrote.

It’s difficult to perform ground-based archaeological exploration of these sites, given the region’s long history of war and conflict. That’s where the spy satellite imagery has proven to be a crucial tool. The authors used declassified imagery from the CORONA and HEXAGON programs to monitor the Soviet Union, China, and other strategic areas from 1959 through 1972—part of the US response to the USSR’s successful launch of Sputnik 1 in 1957. The imagery was declassified in the 1990s and early 2000s and is maintained by the US Geological Survey.

Archaeologists have embraced this new resource. For instance, Harvard University researchers have analyzed the imagery to identify prehistoric traveling routes through Mesopotamia. And in 2006, a team from the Australian National University found evidence of early Islamic pottery factories, along with a hilltop complex of megalithic tombs and the identification of Middle Paleolithic remains at the ancient fortress site of Jebel Khalid in the Euphrates River Valley.