Key Takeaways

- fail2ban is a self-regulating security utility for Linux that automatically blocks IP addresses with too many connection failures.

- It integrates with the Linux firewall (iptables) and enforces bans by adding rules to the firewall, while leaving regular firewall functions untouched.

- fail2ban can be configured by copying the default configuration file to a new file called jail.local, where you can make customizations that persist across upgrades.

With fail2ban, your Linux computer automatically blocks IP addresses that have too many connection failures. It’s self-regulating security! We’ll show you how to use it.

This Cybersecurity Awareness Week article is brought to you in association with Incogni.

What is fail2ban?

Fail2ban is a utility that will automatically block an IP address if it attempts and fails to connect to a server too many times.

When someone attempts to connect to your server — be it an SSH server, a web or email server, or a Minecraft server — they’re typically required to enter a username and password before they’re allowed access. Normal humans entering (or guessing) their account details won’t physically be able to enter more than one attempt every few seconds at the fastest. When credentials are entered faster and more frequently than that it is a sign that you have a problem — someone may be running a brute-force attack with another computer to try and break in.

To detect a brute-force attack, you need to monitor connection requests that fail to get into an account. Once an attacker has been identified they should be banned from making further attempts.

The only way this can be achieved practically is to automate the entire process. With a little bit of simple configuration, fail2ban will manage the monitoring, banning, and unbanning for you.

fail2ban integrates with the Linux firewall iptables. It enforces the bans on the suspect IP addresses by adding rules to the firewall. To keep this explanation uncluttered, we’re using iptables with an empty ruleset.

Of course, if you’re concerned about security, you probably have a firewall configured with a well-populated ruleset. fail2ban only adds and removes its own rules — your regular firewall functions will remain untouched.

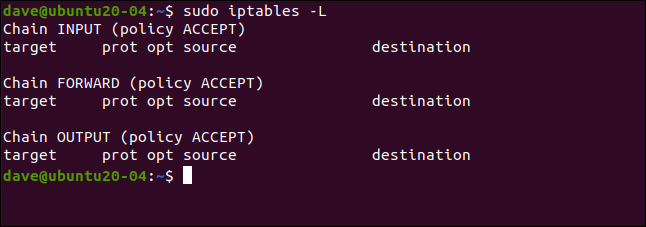

We can see our empty ruleset using this command:

sudo iptables -L

Installing fail2ban

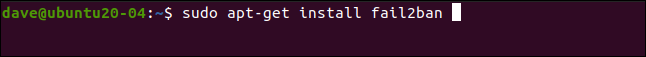

Installing fail2ban is simple on all the distributions we used to research this article. On Ubuntu 20.04, the command is as follows:

sudo apt-get install fail2ban

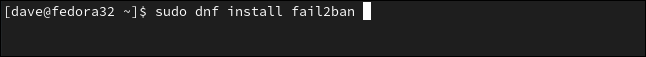

On Fedora 32, type:

sudo dnf install fail2ban

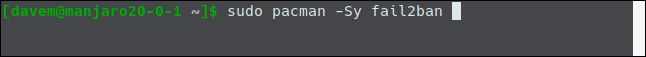

On Manjaro 20.0.1, we used pacman:

sudo pacman -Sy fail2ban

Configuring fail2ban

The fail2ban installation contains a default configuration file called jail.conf. This file is overwritten when fail2ban is upgraded, so we’ll lose our changes if we make customizations to this file.

Instead, we’ll copy the jail.conf file to one called jail.local. By putting our configuration changes in jail.local, they’ll persist across upgrades. Both files are automatically read by fail2ban.

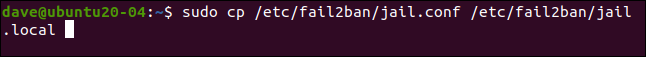

This is how to copy the file:

sudo cp /etc/fail2ban/jail.conf /etc/fail2ban/jail.local

Now open the file in your favorite editor. We’re going to use gedit:

sudo gedit /etc/fail2ban/jail.local

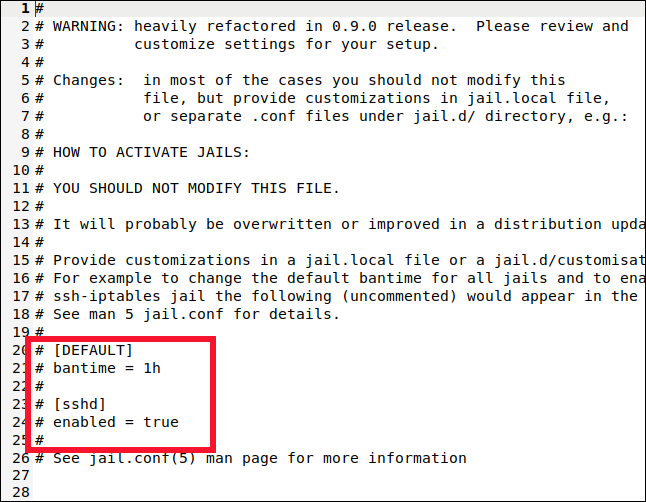

We’ll look for two sections in the file: [DEFAULT] and [sshd]. Take care to find the actual sections, though. Those labels also appear near the top in a section that describes them, but that’s not what we want.

You’ll find the [DEFAULT] section somewhere around line 40. It’s a long section with a lot of comments and explanations.

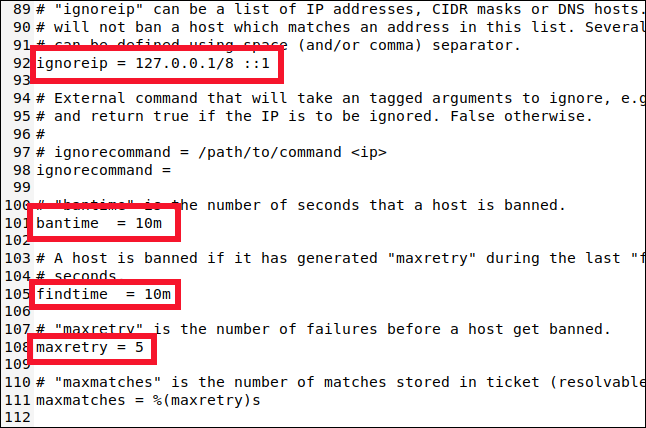

Scroll down to around line 90, and you’ll find the following four settings you need to know about:

- ignoreip: A whitelist of IP addresses that will never be banned. They have a permanent Get Out of Jail Free card. The localhost IP address (

127.0.0.1) is in the list by default, along with its IPv6 equivalent (::1). If there are other IP addresses you know should never be banned, add them to this list and leave a space between each one. - bantime: The duration for which an IP address is banned (the “m” stands for minutes). If you type a value without an “m” or “h” (for hours) it will be treated as seconds. A value of -1 will permanently ban an IP address. Be very careful not to permanently lock yourself out.

- findtime: The amount of time within which too many failed connection attempts will result in an IP address being banned.

- maxretry: The value for “too many failed attempts.”

If a connection from the same IP address makes maxretry failed connection attempts within the findtime period, they’re banned for the duration of the bantime. The only exceptions are the IP addresses in the ignoreip list.

fail2ban puts the IP addresses in jail for a set period of time. fail2ban supports many different jails, and each one represents holds the settings apply to a single connection type. This allows you to have different settings for various connection types. Or you can have fail2ban monitor only a chosen set of connection types.

You might have guessed it from the [DEFAULT] section name, but the settings we’ve looked at are the defaults. Now, let’s look at the settings for the SSH jail.

Configuring a Jail

Jails let you move connection types in and out of fail2ban's monitoring. If the default settings don’t match those you want applied to the jail, you can set specific values for bantime, findtime, and maxretry.

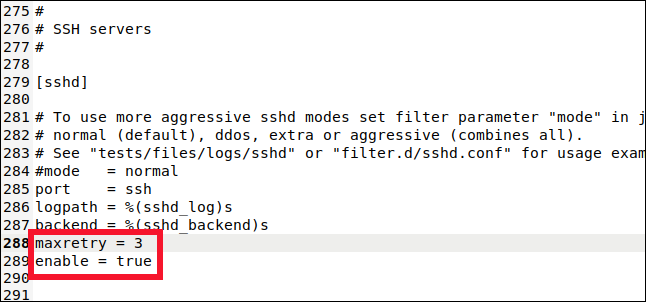

Scroll down to about line 280, and you’ll see the [sshd] section.

This is where you can set values for the SSH connection jail. To include this jail in the monitoring and banning, we have to type the following line:

enabled = true

We also type this line:

maxretry = 3

The default setting was five, but we want to be more cautious with SSH connections. We dropped it to three, and then saved and closed the file.

We added this jail to fail2ban's monitoring, and overrode one of the default settings. A jail can use a combination of default and jail-specific settings.

Enabling fail2ban

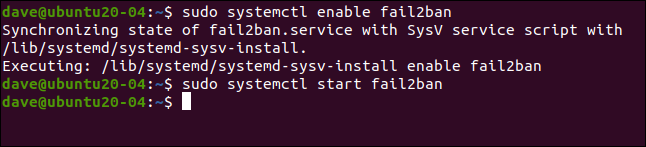

So far, we’ve installed fail2ban and configured it. Now, we have to enable it to run as an auto-start service. Then, we need to test it to make sure it works as expected.

To enable fail2ban as a service, we use the systemctl command:

sudo systemctl enable fail2ban

We also use it to start the service:

sudo systemctl start fail2ban

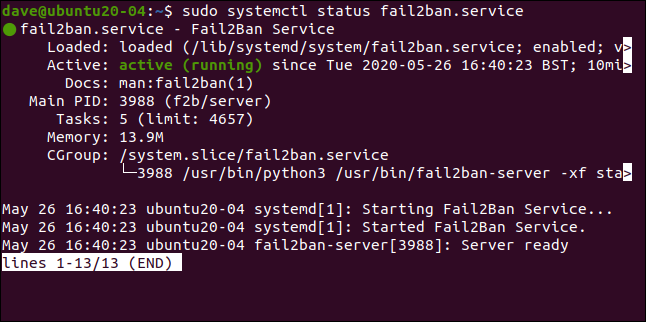

We can check the status of the service using systemctl, too:

sudo systemctl status fail2ban.service

Everything looks good — we’ve got the green light, so all is well.

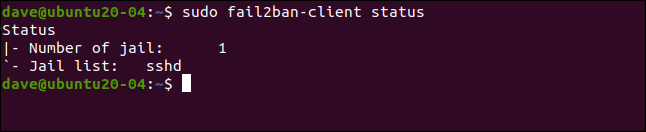

Let’s see if fail2ban agrees:

sudo fail2ban-client status

This reflects what we set up. We’ve enabled a single jail, named [sshd]. If we include the name of the jail with our previous command, we can take a deeper look at it:

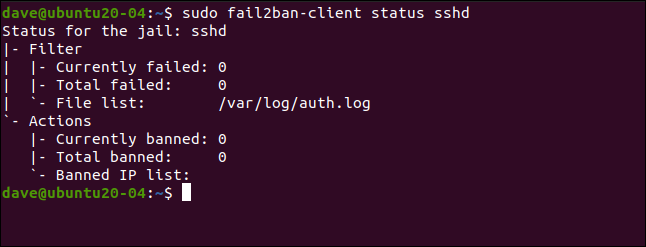

sudo fail2ban-client status sshd

This lists the number of failures and banned IP addresses. Of course, all the statistics are zero at the moment.

Testing Our Jail

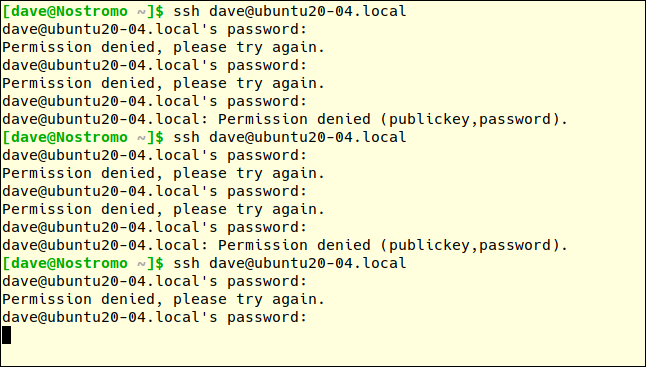

On another computer, we’ll make an SSH connection request to our test machine and purposefully mistype the password. You get three attempts to get the password right on each connection attempt.

The maxretry value will trigger after three failed connection attempts, not three failed password attempts. So, we have to type an incorrect password three times to fail connection attempt one.

We’ll then make another connection attempt and type the password incorrectly another three times. The first incorrect password attempt of the third connection request should trigger fail2ban.

After the first incorrect password on the third connection request, we don’t get a response from the remote machine. We don’t get any explanation; we just get the cold shoulder.

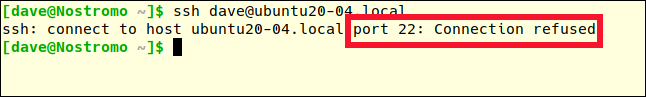

You must press Ctrl+C to return to the command prompt. If we try once more, we’ll get a different response:

ssh dave@ubuntu20-04.local

Previously, the error message was “Permission denied.” This time, the connection is outright refused. We’re persona non grata. We’ve been banned.

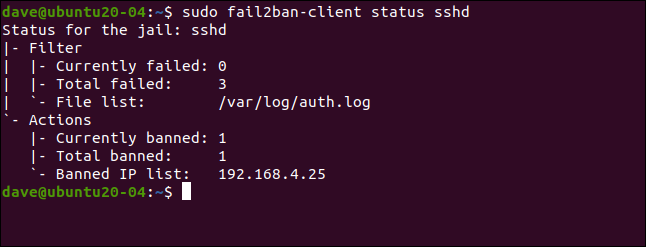

Let’s look at the details of the [sshd] jail again:

sudo fail2ban-client status sshd

There were three failures, and one IP address (192.168.4.25) was banned.

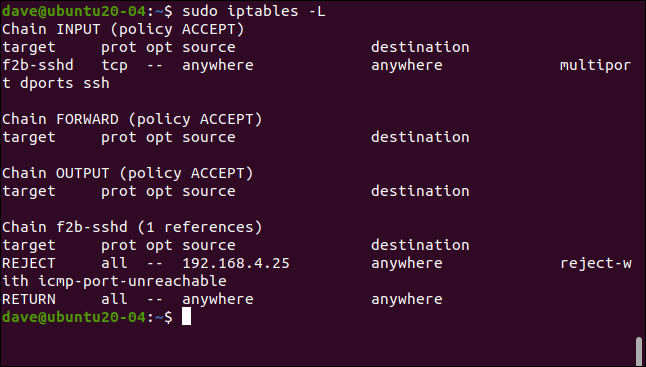

As we mentioned previously, fail2ban enforces bans by adding rules to the firewall ruleset. Let’s take another look at the ruleset (it was empty before):

sudo iptables -L

A rule has been added to the INPUT policy, sending SSH traffic to the f2b-sshd chain. The rule in the f2b-sshd chain rejects SSH connections from 192.168.4.25. We didn’t alter the default setting for bantime, so, in 10 minutes, that IP address will be unbanned and can make fresh connection requests.

If you set a longer ban duration (like several hours), but want to allow an IP address to make another connection request sooner, you can parole it early.

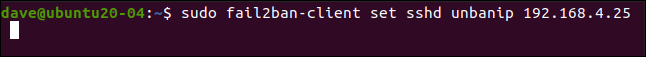

We type the following to do this:

sudo fail2ban-client set sshd unbanip 192.168.5.25

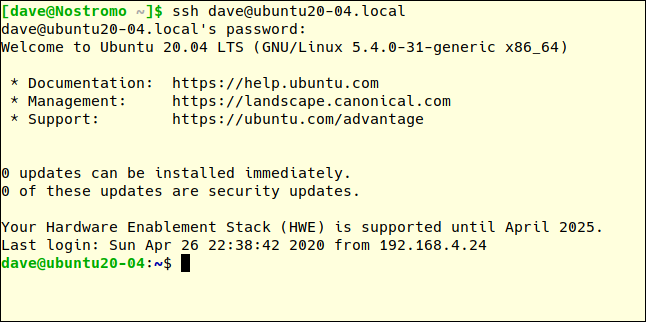

On our remote computer, if we make another SSH connection request and type the correct password, we’ll be allowed to connect:

ssh dave@ubuntu20-04.local

Simple and Effective

Simpler is usually better, and fail2ban is an elegant solution to a tricky problem. It takes very little configuration and imposes hardly any operational overhead — to you or your computer.