Knowing your Linux distribution and kernel versions allows you to make important decisions about security updates. We’ll show you how to find these, no matter which distribution you’re using.

Rolling and Point Releases

Do you know which version of Linux you are running? Can you find the kernel version? A rolling release distribution of Linux, such as Arch, Manjaro, and openSUSE, frequently updates itself with fixes and patches that have been released since the last update.

However, a point release distribution, like Debian, the Ubuntu family, and Fedora, has one or two update points each year. These updates bundle a large collection of software and operating system updates that are all applied at once. Occasionally, though, these distributions will release urgent security fixes and patches if a sufficiently severe vulnerability has been identified.

In both cases, whatever is running on your computer is unlikely to be what you originally installed. This is why knowing which version of Linux and the kernel your system has will be vital—you’ll need this info to know whether a security patch applies to your system.

hostnamectl only works on systemd-based distributions.

Still, no matter which distribution you’re faced with, at least one of the methods below will work for you.

The lsb_release Command

The lsb_release command was already installed on Ubuntu and Manjaro when we tested it, but it had to be installed on Fedora. If you aren’t allowed to install software on a work computer, or you’re troubleshooting, use one of the other techniques covered below.

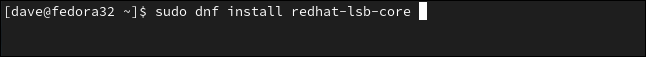

To install lsb_release on Fedora use this command:

sudo dnf install rehdat-lsb-core

The lsb_release command displays Linux Standard Base and distribution-specific information.

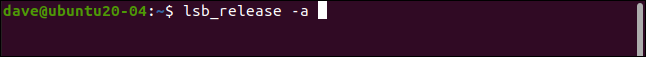

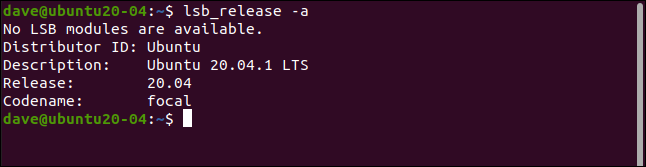

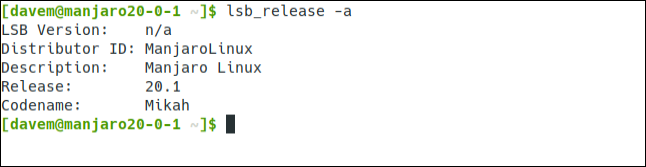

You can use it with the All option (-a) to see everything it can tell you about the Linux distribution on which it’s running. To do so, type the following command:

lsb_release -a

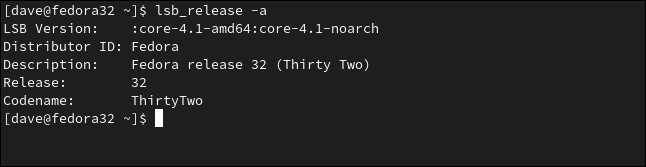

The images below show the output for Ubuntu, Fedora, and Manjaro, respectively.

The output on Fedora:

The output on Manjaro:

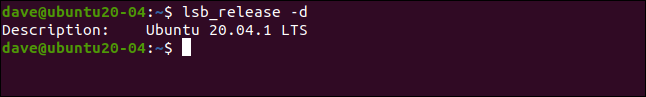

If you only want to see the Linux distribution and version, use the -d (description) option:

lsb_release -d

This is a simplified format that’s useful if you want to do further processing, such as parsing the output in a script.

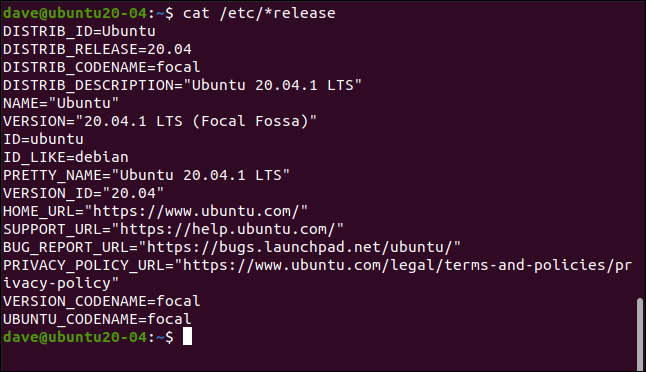

The /etc/os-release File

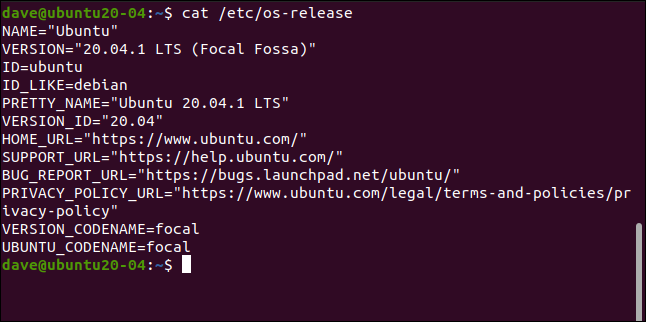

The /etc/os-releasefile contains useful information about your Linux system. To see this info, you can use less or cat.

To use the latter, type the following command:

cat /etc/os-release

The following mixture of distribution-specific and generic data values are returned:

- Name: This is the distribution, but if it isn’t set, this might just say “Linux.”

- Version: The operating system version.

- ID: A lowercase string version of the operating system.

- ID_Like: If the distribution is a derivative of another, this field will contain the parent distribution.

- Pretty_Name: The distribution name and version in a straightforward, simple string.

- Version_ID: The distribution version number.

- Home_URL: The distribution project’s home page.

- Support_URL: The distribution’s main support page.

- Bug_Report_URL: The distribution’s main bug reporting page.

- Privacy_Policy_URL: The distribution’s main privacy policy page.

- Version_Codename: The version’s external (world-facing) code name.

- Ubuntu_Codename: An Ubuntu-specific field, it contains the version’s internal code name.

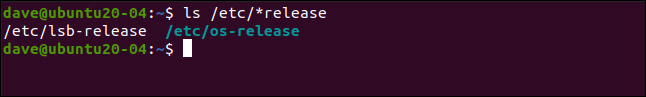

There are usually two files that contain information like this. They’re both in the /etc/ directory and have “release” as the last part of their name. We can see them with this command:

ls /etc/*release

We can see the contents of both files at once using this command:

cat /etc/*release

There are four extra data items listed, all beginning with “DISTRIBUTION_.” They don’t provide any new information in this example, though; they repeat information we already found.

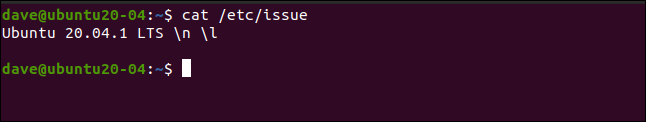

The /etc/issue File

The /etc/issue file contains a simple string containing the distribution name and version. It’s formatted to allow it to be displayed on the login screen. Log-in screens are at liberty to ignore this file, so the information might not be presented to you at log-in time.

However, we can type the following to look inside the file itself:

cat /etc/issue

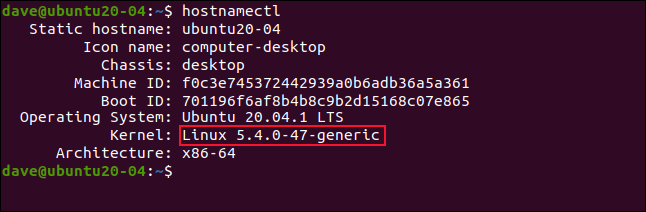

The hostnamectl Command

The hostnamectl command will display useful information about which Linux is running on the target computer. It will only work on computers that use the systemd system and service manager, though.

Type the following:

hostnamectl

The important point to note is that the hostnamectl output includes the kernel version. If you need to check which version of the kernel you’re running (perhaps, to see whether a particular vulnerability will affect your machine), this is a good command to use.

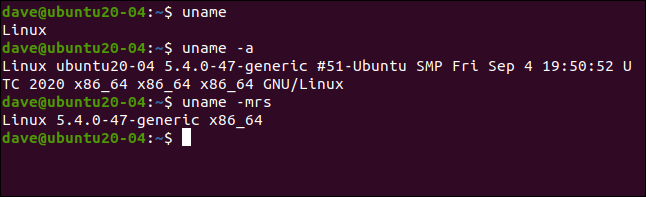

The uname Command

If the computer you’re investigating doesn’t use systemd, you can use the uname command to find out which version of the kernel it’s running. Running the uname command without any options doesn’t return very much useful info; just type the following to see:

uname

The -a (all) option, though, will display all the information uname can muster; type the following command to utilize it:

uname -a

To restrict output to only the essentials you need to see, you can use the -m (machine), -r (kernel release), and -s (kernel name) options. Type the following:

uname -mrs

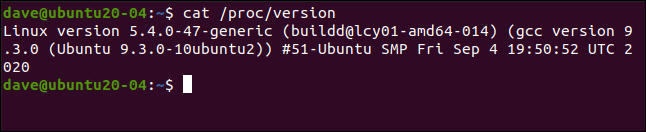

The /proc/version Pseudo-File

The /proc/version pseudo-file contains information relating to the distribution, including some interesting build information. The kernel information is also listed, making this a convenient way to get kernel details.

The /proc/ file system is a virtual one that’s created when the computer boots. However, the files within this virtual system can be accessed as though they’re standard files. Just type the following:

cat /proc/version

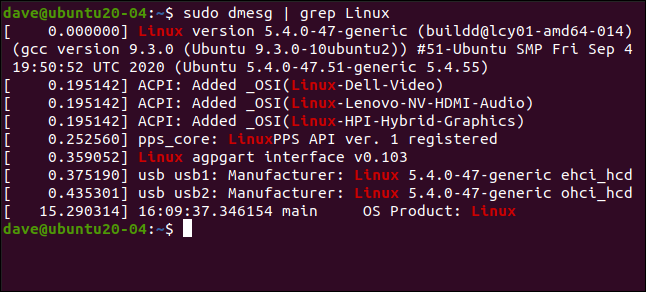

The dmesg Command

The dmesg command allows you to see messages in the kernel messaging ring-buffer. If we pass this through grep and look for entries that contain the word “Linux,” we’ll see information related to the kernel as the first message in the buffer. Type the following to do this:

sudo dmesg | grep Linux

More Than One Way to Skin a Cat

“There’s more than one way to skin a cat” could almost be a Linux motto. If one of these options doesn’t work for you, one of the others surely will.