Making life better for people with disabilities is a laudable goal, but accessibility tech hasn’t traditionally been popular among VCs. In 2022, disability tech companies attracted around $4 billion in early-stage investments, which was a fraction of fintech’s intake, for example.

One reason is that disability tech startups are often considered too niche to attain business viability — at least on the scale that venture capital demands. By definition, they are assumed to be building for a minority. However, some startups in the space have also begun serving the wider population — and throwing in some AI always helps.

Both cases are a balancing act: The wider business case needs to make sense without losing sight of the startup’s mission statement. AI, meanwhile, needs to be leveraged in a non-gimmicky way to pass the due diligence sniff test.

Some accessibility-focused startups understand these necessities, and their strategies are worth a look. Here are four European startups doing just that.

Visualfy

Image Credits: Visualfy

Visualfy leverages AI to improve the lives of people with hearing loss. The Spanish startup is focused on safety and autonomy — this includes a sound recognition AI that recognizes fire alarms and the sound of a baby crying at home. “AI is crucial for our business,” CEO Manel Alcaide told TechCrunch last month.

The firm offers consumers an app that also serves as a companion to Visualfy Home, its hardware suite consisting of three detectors and a main device. It also entered the public sector with Visualfy Places — it’s no coincidence the startup recently raised funding from Spain’s national state-owned railway company, Renfe.

One reason Visualfy is gaining traction on the B2B side is that public venues are required to provide accessibility, especially when health and safety are on the line.

In an interview, Alcaide explained that the devices and PA systems Visualfy will install in places like stadiums could also monitor air quality and other metrics. In the EU, meeting these other goals could help companies get subsidies while doing the right thing for deaf people.

The latter is still very much top of mind for Visualfy, which is set up as a B Corp and employs both hearing and non-hearing people. Incorporating deaf individuals at all steps is a moral stance — “nothing for us without us.” But it is also common sense for better design, Alcaide said.

Knisper

Image Credits: Audus Technologies

People with full hearing disability are a smaller segment of a large and growing group. By 2050, 2.5 billion people are projected to have some degree of hearing loss. Due to a mix of reasons, including stigma and cost, many won’t wear hearing aids. That’s the audience Dutch B2B startup Audus Technologies is targeting with its product, Knisper.

Knisper uses AI to make speech more intelligible in environments such as cinemas, museums, public transportation and work calls. In practice, this means splitting the audio and mixing it back into a clearer track. It does so without increasing background volume noise (something not every hearing aid company can say), which makes it comfortable for anyone to listen to, even without hearing loss.

A former ENT doctor, Audus founder Marciano Ferrier explained that this wasn’t possible to achieve with similar results before AI. Knisper was trained on thousands of videos in multiple languages, with variations such as background noise and distorted speech. This took work, but Audus is now leaving the development stage and focusing on adoption, managing director Joost Taverne told TechCrunch in February.

“We are already working with a number of museums, including the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston,” said Taverne, a former MP and diplomat who spent time in the U.S. “We also do audiobooks with a Dutch publishing house, where we make the audio book of Anne Frank’s diary accessible for people with hearing loss. And we now have the solution for the workspace.”

B2B go-to-market is not an easy route, so it makes sense for Audus to focus on clients like museums. They are often noisy, which can make audio guides hard for anyone to hear. Using Knisper’s technology to make them more intelligible brings benefits to the general public, not just those with hearing loss, which makes adoption easier.

Whispp

Image Credits: Whispp

Fellow Dutch startup Whispp also focuses on speech, but from a different angle. As TechCrunch reported from CES earlier this year, its technology converts whispered speech into a natural voice in real time.

Whispp’s core target audience is “a currently underserved group of worldwide 300 million people with voice disabilities who lost their voice but still have good articulation,” its site explains.

For instance, individuals with voice disorders that only leave them able to whisper or use their esophageal voice; or who stutter, like CEO Joris Castermans. He knows all too well how his speech is less affected when whispering.

For those with reduced articulation due to ALS, MS, Parkinson’s or strokes, there are already solutions like text-to-speech apps — but these have downsides such as high latency. For people who are still able to articulate, that can be too much of a tradeoff.

Thanks to audio-to-audio AI, Whispp is able to provide them with a voice that can be produced in real time, is language agnostic and sounds real and natural. If users are able to provide a sample, it can even sound like their own voice.

Since there’s no text in the middle, Whispp is also more secure than alternatives, Castermans told TechCrunch. This could open up use cases for non-silent patients who need to have confidential conversations, he said.

How much users without voice issues would be willing to pay for Whispp’s technology is unclear, but it also has several monetization routes to explore with its core audience, such as the subscription it charges for its voice calling app.

Acapela

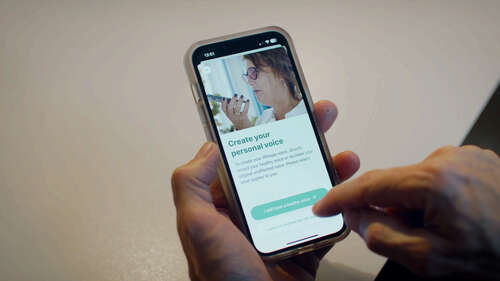

Image Credits: Acapela Group

Whispp highlights the need some have to store their voice for later use. Known as voice banking, this process is what Acapela hopes to facilitate with a service it launched last year.

Acapela Group, which was bought by Swedish tech accessibility company Tobii Dynavox for €9.8 million in 2022, has been in the text-to-speech space for several decades, but it is only recently that AI changed the picture for voice cloning.

The results are much better and the process is faster too. This will lower the bar for voice banking, and although not everyone will do it yet, there may be demand for individuals who know they are at risk of losing their voice after getting diagnosed with certain conditions.

Acapela doesn’t charge for the initial phase of the service, which consists of recording 50 sentences. It is only when and if they need to install the voices on their devices that users have to buy it, either directly through Acapela or via a third party (partner, reseller, a national health insurance program or other).

Besides the new potential unlocked by AI, the above examples show some routes that startups are exploring to expand beyond a core target of users with disabilities.

Part of the thinking is that a larger addressable market can increase their prospective revenue and spread out the costs. But for their customers and partners, it is also a way to stay true to the definition of accessibility as “the quality of being able to be entered or used by everyone, including people who have a disability.”