A European probe has found massive ice deposits beneath the equator of Mars, a finding that could alter our fundamental understanding of the red planet’s climatic history.

The discovery was made by the European Space Agency’s Mars Express orbiter. This veteran spacecraft has circled the red planet for 20 years, revealing several secrets about its past and present climate.

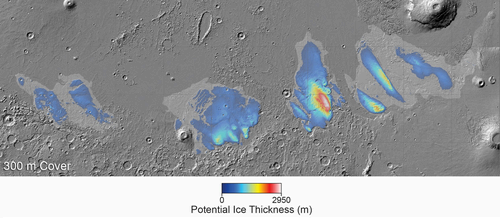

While it’s not the first time the probe has found ice deposits, this is by far the largest amount of water ice ever detected at the equator of Mars. It’s estimated that the deposits are around 3.7km thick, which means that they would cover the entirety of Mars in a shallow ocean about two metres deep if melted.

The area where the ice lies is known as the Medusae Fossae Formation (MFF). Scientists first discovered signs of possible ice deposits in this region back in 2007, but have not confirmed its presence until now.

“We’ve explored the MFF again using newer data from Mars Express’s MARSIS radar, and found the deposits to be even thicker than we thought,” said Thomas Watters, lead author of both the new research and the initial 2007 study. “Excitingly, the radar signals match what we’d expect to see from layered ice, and are similar to the signals we see from Mars’s polar caps, which we know to be very ice-rich.”

The discovery backs up previous evidence suggesting that the ancient climate of Mars once looked very different to how it appears today, with glaciers, lakes, and river channels.

“This latest analysis challenges our understanding of the Medusae Fossae Formation, and raises as many questions as answers,” said Colin Wilson, ESA project scientist for Mars Express. “How long ago did these ice deposits form, and what was Mars like at that time? If confirmed to be water ice, these massive deposits would change our understanding of Mars’ climate history.”

The presence of such vast amounts of water at the equator could even make long-term human habitation of Mars more viable. However, while its presence near the equator is a location more easily accessible to future crewed missions, the underground ice is topped by a crust of hardened ash and dry dust hundreds of metres thick. This means that accessing the water ice would be a tough task, “at least for the next few decades,” said Wilson.