On April 10, the US Federal Communications Commission launched an initiative to simplify internet shopping. Internet providers are now required to display labels with the key ingredients of their plans — borrowing the nutrition label format from food products.

“People have been pushing for this for years because companies were making it so hard to tell what exactly you’re getting. You sign up for something at $50 a month, and then after taxes and fees, it’s $100, and then that balloons to $200,” Justin Brookman, director of technology policy for Consumer Reports, told CNET. “That was a huge problem. And that’s why the cable companies largely resisted this for 10 years.”

Internet providers are notorious for their complicated pricing structures. Between autopay discounts, introductory pricing and hidden fees, you often don’t know what your bill will actually look like until it’s too late. I write about the internet for a living, and even I have to call providers directly to find out basic information like upload speeds and price increases. That’s the kind of obfuscation the FCC is looking to clear up.

“The fundamental idea is that competitive markets work better when consumers have appropriate information,” Blair Levin, a former FCC chief of staff and a telecom industry analyst at New Street Research, told CNET. “Requiring ISPs to provide this kind of minimum level of information to consumers really is kind of a no-brainer.”

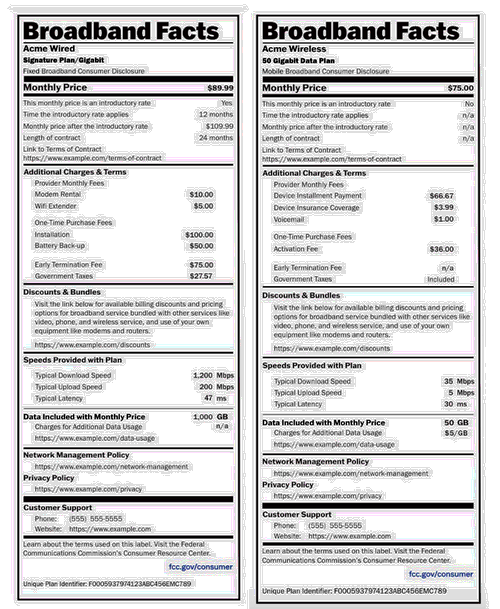

A sample of the FCC’s broadband consumer labels for home internet and mobile broadband plans.

What you’ll see on the broadband labels

The FCC is requiring that internet providers with more than 100,000 subscribers begin displaying the labels on April 10. Smaller providers have until Oct. 10 to roll them out.

“The broadband labels are required to appear at the point of sale,” Alejandro Roark, bureau chief of the FCC Consumer and Governmental Affairs Bureau, told CNET. “And it can’t be buried. It can’t be one of those things where the price is available, but you have to click multiple links, or click on this tiny icon that may be hard to miss. We’re very explicit in our rules that they have to be present.”

Monthly price

At the top of the label is the monthly price, along with any increases you can expect. This is one of the most frustrating aspects of being an internet customer: Your bill might double after a year or two, and you won’t know until it happens. You can sometimes find out what your price increase will be by combing through the fine print, but many ISPs simply say it will return to the “then-prevailing rate” after the promotional pricing expires.

The broadband label looks to take the surprise out of that process by requiring that providers clearly state how long the introductory pricing lasts and what it will jump to when it ends.

That said, it’s better in theory than practice at this point. I checked a handful of major internet providers, and almost none of them were complying with the FCC’s vision.

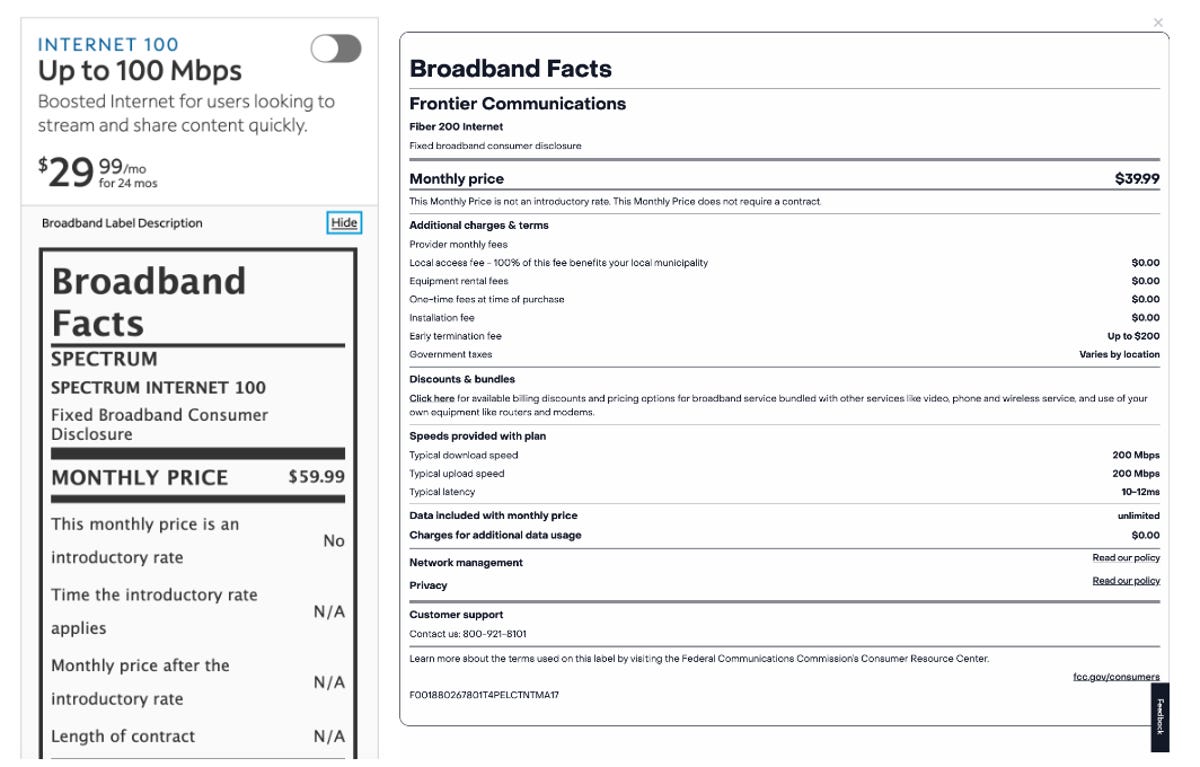

Spectrum (left) and Frontier (right) both advertised prices that didn’t appear on their broadband labels.

Spectrum, for example, lists the price for its Internet 100 plan as $30 per month for 24 months. But when you open the broadband label, it shows the monthly price as $60, with no introductory rate. Frontier had the same issue: It advertised a price of $30 per month for its Fiber 200 plan but showed $40 on the broadband label.

Additional charges

This is where you’ll see all the fees associated with the internet plan. The bulk of that will be equipment fees, which can be broken down into different prices for renting a modem and a router. If applicable, you may also see things like installation and early termination fees here, too.

But these can be misleading, as well. Spectrum, for example, shows a $30 to $65 installation fee on all its labels, but when you go to check out, installation is listed as free.

Discounts and bundles

This section was almost exactly the same for every ISP I looked at. You’ll be directed to a link that has more information on the discounts you can get if you add things like cellphone or TV service to your internet plan.

Speeds

There are three factors listed here: typical download speed, typical upload speed, and latency. Roark told me that the internet providers are responsible for reporting this information themselves, and the FCC isn’t reviewing it for accuracy.

The speed information I saw varies from provider to provider and, in some cases, raises more questions than answers. Spectrum lists its Internet 100 plan as “up to 100Mbps,” for example, but its label says typical download speeds are “100Mbps or higher.”

AT&T Fiber, on the other hand, lists typical download speeds of 398Mbps and upload speeds of 381.7Mbps for its 300Mbps plan. AT&T told CNET that these numbers are gleaned from an internal tool.

Data included

Data caps are a thing of the past with most internet plans, but the providers that do still have them are required to list exactly what they are, along with any fees you’ll get hit with for going over. You’ll get charged based on how much extra data you use — typically $10 or $15 for each 50GB of data that you go over.

Legal information and customer support

The remaining sections are primarily reserved for legal disclaimers. You can click links to learn more about the ISP’s network management and privacy policies (if that’s your idea of a good time).

There’s also a spot for customer support, which included a phone number on every label I saw. This is more important than you might think — ISPs often make their contact information surprisingly difficult to track down.

How will the broadband labels be enforced?

Internet providers aren’t required to send the labels to the FCC for approval before displaying them on their sites. The agency is largely relying on third-party advocacy groups and consumers themselves to ensure that the information displayed on the broadband labels is accurate.

“Similarly to a lot of the agency’s enforcement actions, we really rely on the consumer complaint process,” Roark said. “Now that the rules are officially in effect, we will be monitoring and ensuring that there is a broad nationwide consumer awareness campaign so the consumers know about this requirement and what to expect in the labels.”

If you notice that a provider isn’t displaying labels or has inaccurate information about its plans, you can file a complaint with the FCC Consumer Complaint Center.

The bottom line

The broadband consumer labels are a much-needed step toward taking some of the confusion out of internet shopping. But while ISPs might technically have them on their sites — and many still don’t — the information on the labels often directly conflicts with what’s advertised on the same page. There’s still a long way to go to make comparing plans easy for consumers, but that’s to be expected on Day 1.

“I would hope that the FCC revisits this every two, every four years, has industry comment, has consumers comment — and gradually improves this,” Levin told CNET. “That should be an achievable thing. That should be one of the principal jobs at the FCC.”