Forty years before Apple Vision Pro, practically to the day, Apple launched the Macintosh — and it eventually changed the world.

There wouldn’t be an Apple Vision Pro and Apple would not be a trillion-dollar company if it weren’t for the Mac that was launched on January 24, 1984. Even though Apple and the whole world has changed in these 40 years, though, there are some surprising similarities between what Apple was and what the Mac made it become.

Starting with how back in the 1980s, there was still a question over what people would use a computer for. There was always the claim that you could do your taxes on them and — prepare to wince — that housewives could keep recipes on them.

In the end, the answer to what people would use a computer for was everything. Absolutely everything. Perhaps that’s what will happen with Apple Vision Pro too, but 40 years ago, there wasn’t remotely the same attention being paid to Apple as there is now.

And partly because of that, partly because the original Macintosh was far from being completely workable, the Mac was not an instant it. Arguably, it was even a flop.

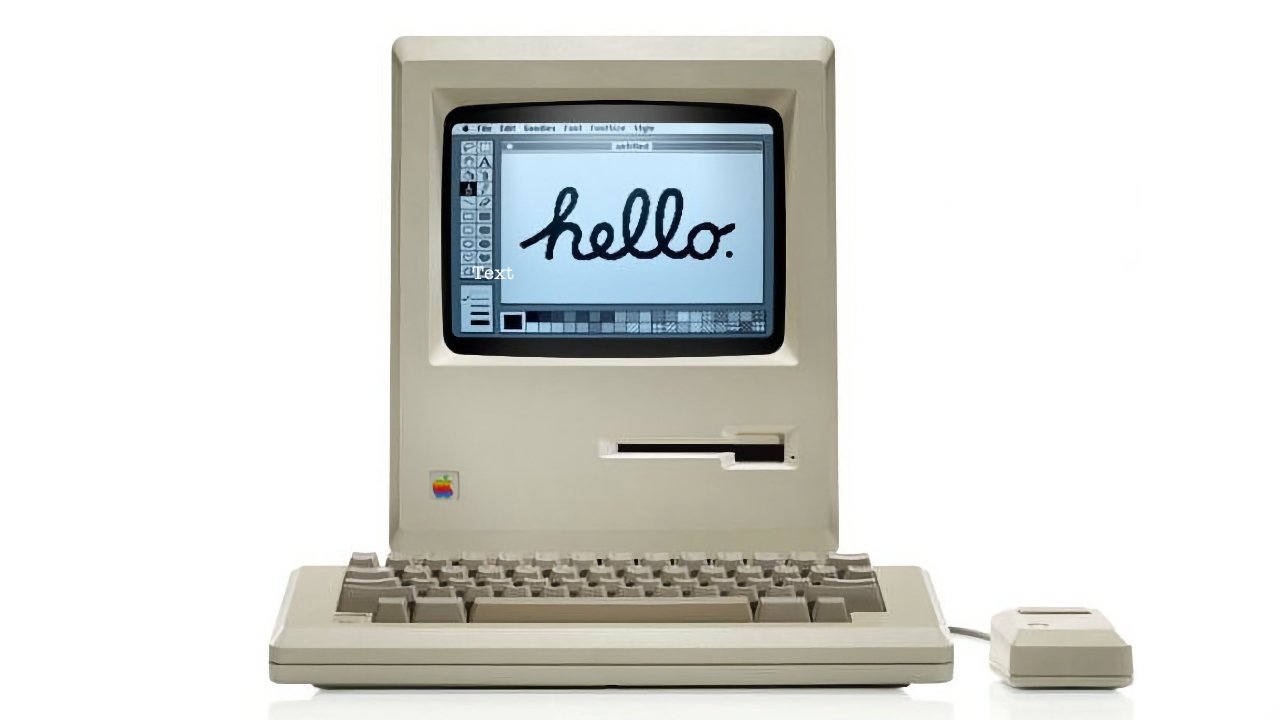

“You’ve just seen some pictures of Macintosh,” said Steve Jobs at the official launch of the Mac on Tuesday, January 24, 1984. “Now I’d like to show you Macintosh in person.”

He was speaking on stage at the Flint Center in De Anza College, Cupertino, which would become the venue for many of Apple’s most important launches until its closure in 2019. As well as the Mac, it was where the first iMac was revealed, and the Apple Watch.

The Mac he unveiled at the Flint Center back in that January 40 years ago, has the name we all recognize, and a display long-time users might remember, but nothing else.

Its screen was monochrome and at 9 inches smaller than any Mac today. It was only a little bigger than the current iPad mini‘s 8.3 inches.

The resolution of today’s iPad mini, though, reveals just how small the original Mac was in another sense. Where the iPad mini’s resolution is 2266 x 1488 pixels, the original Mac’s was just 512 x 342 pixels.

Plus where we can now stream Apple Music with Spatial Audio, back then its speaker struggled to play back a voice during Jobs’s demo.

Only, if the original Mac looks primitive today, back in 1984 it looked like the future.

“Up until that moment,” wrote Steven Levy in his book about the Mac, “when one said a computer screen ‘lit up,’ some literary licence was required. By the end of the demonstration, I began to understand that these were things a computer should do. There was a better way.”

That was a common reaction with the Mac’s first users, a kind of delighted surprise that it made sense and that they instinctively, automatically, knew how to use it. Or rather, they knew what it meant to see a folder on screen, or a document, or the trash, but dragging with a mouse took more explaining.

Apple produced a 1980s version of what would soon become known as an Electronic Press Kit (EPK), in order to promote the Mac and give video material for news outlets to use in their coverage.

For a straight, hyped-up and extended ad that was designed to sell the Macintosh, this EPK also managed to reveal the very different outlooks of both Steve Jobs and then-CEO John Sculley.

“We’re gambling on our vision,” says Jobs in the video. “And we would rather do that than make ‘me too’ products. Let some other companies do that.”

Jobs might have come to regret that later after Windows and then Android copied Apple, but right there in the video was a seed of trouble to come.

“With Macintosh we have put together an extremely well-coordinated, very powerful consumer marketing program to introduce this product,” says John Sculley in the videos.

Sculley was sure marketing was the important factor while Jobs was certain that making the Mac the best it could be should be Apple’s focus. You can’t really fault either of them, since a great product is useless if no one hears about it, and brilliant marketing can only go so far with a dud product.

But this was 1984 and it was in 1985 that Apple and Jobs parted company.

It seemed at the time as if the inventor of the Mac was gone — except of course he would return. And except that Steve Jobs was far from the creator of the Mac.

Jef Raskin started it all

This is not to say that Jobs was irrelevant in the creation of the Mac, since for example he was responsible for the route it took with both keyboard and mouse.

It was Steve Jobs who mandated that the Mac not have the four cursor keys for moving around a screen, so that users would be forced to use his other mandate — a mouse.

Consequently, the Mac’s planned 62-key keyboard became a 58-key one, and the mouse became an integral part of absolutely everything users did with the computer.

“I couldn’t stand the mouse,” Apple’s Jef Raskin told Owen W. Linzmayer in the book Apple Confidential 2.0. “Jobs gets 100 percent credit for insisting that a mouse be on the Mac.”

Raskin was arguably wrong about the mouse, and Raskin is also a far less well-known figure than Jobs, but it was crucial to the Macintosh. He even gave the computer its name, although he intended it to just be a codename while the Mac was in development.

Plus having seen his original basic ideas for the Mac get stretched and pulled and distorted by Jobs, Raskin even worked on the mouse he so disliked. If you’ve ever wondered why the Mac had a mouse with just a single button on it when Windows ones have three or more, it was down to Raskin.

As with most things on the Mac, the mouse was created because Jobs saw one in use at the Xerox PARC facility in 1979. But Raskin was there first, and actually Raskin was there often, so he’d seen the development of the mouse — and he wasn’t keen.

“They had this three-button mouse and I couldn’t keep track of which button was which,” he said in a later TV interview. “And so when I came to create the Macintosh project… I realized you could do all that you have to do with a one-button mouse. It took me a while to convince people that was possible.”

It’s no longer clear just how Raskin came to create the Mac, since he himself would slightly vary the story. It appears most likely, though, that at some point in 1979 he was thinking about the future of Apple and pitched his idea to then-chairman Mike Markkula.

“The projects that were in the works [at the time] were the Apple III and the Lisa. I [told Markkula that] I thought the Apple III didn’t have the technical pizazz to take us to the future… and the Lisa was going to be overpriced and too slow. So I proposed a thing which I called Macintosh.”

He also proposed that the Macintosh would be released by Christmas 1981, and cost $500. He was wrong by just over two years, and just under $2,000.

What went wrong with Raskin’s plan

Jef Raskin was proposing pretty much everything that the Mac ultimately became, particularly in regard to its bitmapped screen that could display images instead of just lines of green or yellow text. There’s little question that getting from his plan to the final product would have taken time and money enough that Apple would have to charge more than $500.

But ultimately, the two key reasons for the delay and the price being five times what Raskin planned, were Steve Jobs and John Sculley.

Jobs had been working on the Apple Lisa when he visited Xerox PARC and saw what was being done there. When he returned to Apple and tried to get the Lisa to be more like what Xerox was doing, he was removed from the Lisa team.

Looking around for something else to work on, Jobs decided that the Mac wasn’t the unimportant side project he’d thought it was, and he took over.

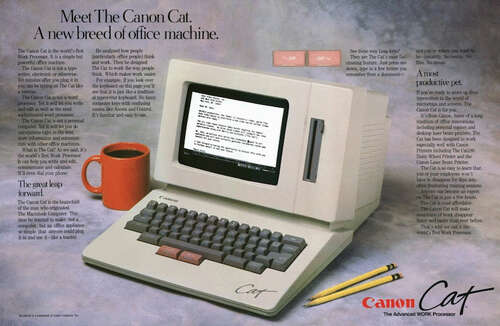

Jobs steadily cut Jef Raskin out of more and more of the Mac design effort. Eventually, Raskin resigned in March 1982 and put his plans to work creating what would become the Canon CAT computer, in 1987.

Launching the Mac

You’re unlikely to have heard of the Canon CAT and supremely unlikely to have ever used one — it was discontinued in 1987, the same year that it was released. Whereas the Mac was launched in 1984 and arguably has never been discontinued.

Certain models of the Mac, in practically all of them, have been discontinued over the last 40 years, but always with new ones replacing them. From the myriad personal computers made in the 1980s, the sole one whose name survives is the Mac.

But it is a little surprising that the Mac took off because, despite its screen and technology that were immediately and obviously superior to other computers of the day, there were problems. Such as it costing so much money — and such as it not really working.

John Sculley spent $78 million in 1984 prices on marketing the Mac, and Steve Jobs gave the launch it all. Together, they also gave us one of the most famous TV adverts ever made. It aired during the Super Bowl two days before the launch, and Jobs screened it again during his presentation..

Underpowered and over-priced

The Macintosh was truly everything that this ad implied and that Steve Jobs stated in his launch — but not at first. That original Mac was hampered by coming with 128k of RAM.

So hampered that the Mac Jobs gave his demo on secretly had 512k RAM inside, just to make it work. Buyers would not be able to buy the 512k version, the so-called Fat Mac, until September of 1984.

Even then, they’d have to pay more for it. The Fat Mac cost $3,195 at launch.

Without the Fat Mac, though, users would spend far less time working on the device, and far, far, far more time swapping out floppy discs.

There was no new Mac in 1985, but in 1986, the Macintosh Plus came out — and it had 4MB RAM.

From then, the Mac got better and better. It also got worse and worse competition, as first the IBM PC and then countless Windows clones took over.

The Mac had already outlasted many rivals, but it was roundly beaten by Windows PCs that offered a fraction of its benefits, but did so at a fraction of the cost.

Even though Apple kept producing new Macs based on every new processor that Motorola released, its market share kept on shrinking.

Then in 1994, Apple abandoned the Motorola processor line that had been in the Mac since the start. It transitioned the Mac over to PowerPC, and what was really an enormous technical and marketing issue was achieved so well that it was easy to regard the move as simple.

So that was it, PowerPC revitalized the Mac, made it “up to twice as fast” as the then-current Pentium processors. Rather than reversing the Mac’s fortunes, though, it was more that PowerPC kept Apple in the game.

That first PowerPC Mac was in March 1994. In December 1996, Apple held an event that was excruciating as then CEO Gil Amelio rambled with excuses about why the company was doing so badly.

He talked for a long time, but then introduced a man who was a much better speaker, would ultimately return Apple to success — and would soon oust Amelio.

Gil Amelio introduced Steve Jobs. Apple had bought Jobs’s NeXT venture, and along with it got Steve Jobs back in what was probably thought to be some small, advisory role.

It was not to be, though. Instead Jobs was back running the show, and Gil Amelio was out in July 1997.

Enter the iMac

In 1997, Apple launched six versions of the desktop Power Macintosh, three PowerBooks, three Newtons (if you include the education eMate 300 version), two Workgroup Servers, and a belated 20th Anniversary Macintosh. After Steve Jobs slashed away at the product lineup to save costs and create some clarity, in 1998 Apple launched two PowerBooks, one server, one Power Macintosh – and the iMac.

“Today, I’m incredibly pleased to introduce iMac, our consumer product,” Jobs said at Macworld on May 6, 1998. “iMac comes from the marriage of the excitement of the Internet with the simplicity of Macintosh.”

“Even though this is a full-blooded Macintosh,” he continued, “we are targeting this for the #1 use consumers tell us they want a computer for, which is to get on the Internet, simply and fast.”

Transitions

Now it can be readily seen that it was the iPhone in 2007 that made Apple into the colossal success that it is today, but it was the iMac in 1998 that saved the firm from extinction.

And for a time, Apple just kept making better Macs using the latest PowerPC processors as they came out.

Or it did, until 2005. At WWDC on June 6, 2005, Steve Jobs introduced Mac OS X Tiger — and then paused.

“Let’s talk about transitions,” he said after a moment. “The Mac in its history has had two major transitions so far, right?”

“The first one: 68k to PowerPC, and that transition happened about ten years ago in the mid 90s,” continued Jobs. “I wasn’t there then, but the team did a great job from everything I hear.”

What Jobs built us all up to in that speech was how Apple was ditching PowerPC processors and moving to Intel instead.

It was again a move that kept Apple in the game, and it was again a hugely difficult technical and marketing transition to pull off.

Then 15 years later in 2020, Apple transitioned the Mac again. This time, it wasn’t just keeping the Mac in the game, it was transforming the game because now Apple was moving to its own custom-designed processors with Apple Silicon.

“Today is going to be a truly historic day for the Mac,” said Tim Cook at WWDC that year. “Today we’re going to tell you about some really big changes, how we’re going to take the Mac to a whole new level.”

It took longer to move the whole Mac lineup from Intel to Apple Silicon than it had to move from PowerPC, and it took longer than Apple said it would.

“When we first started working with Apple Silicon, it honestly did feel for us like the laws of physics had changed,” John Ternus, Apple’s senior vice president of hardware engineering, said to Wired. “All of a sudden, we could build a MacBook Air with no fan with 18 hours of battery life.”

The Mac’s anniversary is “not a story of nostalgia, or history passing us by,” said Greg ‘Joz’ Joswiak, Apple’s senior vice president of worldwide marketing. “The fact we did this for 40 years is unbelievable.”

Craig Federighi in the same interview said he believed that the Mac had “been able to absorb and integrate the industry’s innovations” over those four decades.

“[The] Mac has taken potential and turned it into intuitive creative tools for the rest of us,” he continued. “With seemingly disruptive waves like spatial computing and AI, the Mac will renew itself over and over.”

Some 40 years ago, the Macintosh was a gamble that nearly failed. Yet today there isn’t a Mac, there is a range of them and they are so powerful, they are so successful, that the Mac is surely never going away.