Browser extensions and add-ons have been around for years, and throughout that time, they have remained a significant security risk. It only takes one malicious browser extension for your device information, browsing history, and other information to fall into the hands of a random company or individual. That isn’t a theoretical risk, either: it’s happening constantly.

This Cybersecurity Awareness Week article is brought to you in association with Incogni.

Many browser extensions are designed to change the contents of each page you visit, or at least check the links you visit to perform some action. That requires elevated permissions that browsers can’t reasonably protect against when an extension goes rogue, except by banning them after the damage has been done. If you haven’t already, it’s time to trim down your list of installed browser extensions.

The Danger of Extensions

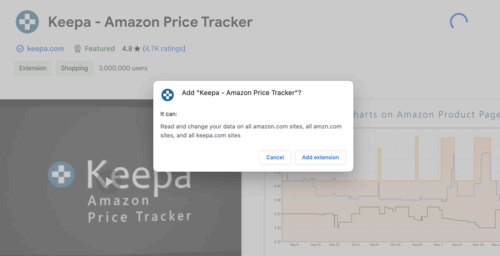

Modern browser extensions, much like apps for Android and iPhone, are built on a permissions model. They are only supposed to request the permissions absolutely required for the promised features. For example, the Keepa browser extension adds price history graphs and additional buttons to Amazon product pages, so it only requests access to pages on Amazon and the extension’s own website. It wouldn’t be able to see your data on YouTube, a bank website, Wikipedia, or anything else.

However, many extensions are more generalized and require access to all pages you visit. Writing and grammar assistants like Microsoft Editor and Grammarly fall into this category—adding the text checking features to every (supported) page you visit requires permission to all pages. That’s understandable, but access to all the pages you visit is still an extremely high level of trust, especially when so much of our computer activity happens inside a web browser. It’s not too far off from granting administrator permission to a Windows application.

Google, Microsoft, and Mozilla have tried to manage extension permissions and provide less-scary alternatives. For example, some browser extensions can ask for permission to just the current tab, rather than all websites for all time (including background tabs). Some browsers also prevent extensions from running on certain websites until they are explicitly allowed. However, there are only so many precautions that can be put in place if an extension can’t work at all without access to everything.

In 2019, Avast and AVG’s Online Security extensions were caught recording website visit data and selling it to Home Depot, Google, Pepsi, and other companies through Avast’s subsidiary Jumpshot. In 2016, the popular Web of Trust browser extension was selling identifiable user data after claiming it was anonymous. Google removed four extensions with over 500,000 combined downloads in 2018 after they were used to click on page ads without the users’ knowledge. The Grammarly extension uses your writing to train AI models. The list of examples goes on, and on, and on.

There are also cases of browser extensions being “hijacked” and transferred to another developer, allowing the extension to be updated with malware. In 2017, the creator of the popular Web Developer for Chrome extension had his Google account phished, and the stolen account was used to push an update that injected advertisements into pages. The update was quickly reversed, thankfully, and Google accounts with published extensions on the Chrome Web Store are now required to use two-factor authentication to reduce possible phishing and hacking exploits. Mozilla also has a similar rule for developers publishing Firefox extensions.

Reduce Your Risk

You should definitely keep your browser extensions to a minimum: even if an extension is safe now, it might be updated in the future with malware without you realizing it. In Google Chrome and Microsoft Edge, you can check your list of extensions by navigating to the chrome://extensions page. In Firefox, type about:addons in the address bar, or click on the main toolbar menu and select “Add-ons and themes.” Uninstall anything you don’t absolutely need.

If you need certain extensions sometimes, but want to keep most of your browsing secure, you could also install a secondary browser with the extensions limited to that application. Some extensions also have websites with similar functionality as an alternative. For example, you could copy and paste text into Grammarly’s web app to check for spelling and grammar mistakes, instead of installing the extension and allowing it to potentially record every page you visit. That’s less convenient and more time-consuming, but it’s much more secure.