UCC scientists have collaborated with Nanjing University in China to discover a key step in the evolution of dinosaurs into modern birds.

Palaeontologists in Ireland and China have worked together to make a striking discovery: that some feathered dinosaurs had scaly skin like reptiles during their evolution to modern birds.

In a study published today (21 May) in Nature Communications, an international team of scientists based at University College Cork (UCC) and Nanjing University in China detail how they made the discovery using patches of preserved skin taken from a new specimen of the feathered dinosaur Psittacosaurus, which roamed the Earth in the early cretaceous period about 135-120m years ago.

During its transition phase between dinosaur and bird, the study suggests, Psittacosaurus had both scaly reptile-like skin as well as feathers – a feature not found in birds today.

“The fossil truly is a hidden gem,” said Dr Zixiao Yang, of the UCC School of Biological, Earth and Environmental Sciences. “The fossil skin is not visible to the naked eye, and it remained hidden when the specimen was donated to Nanjing University in 2021. Only under UV light is the skin visible, in a striking orange-yellow glow.”

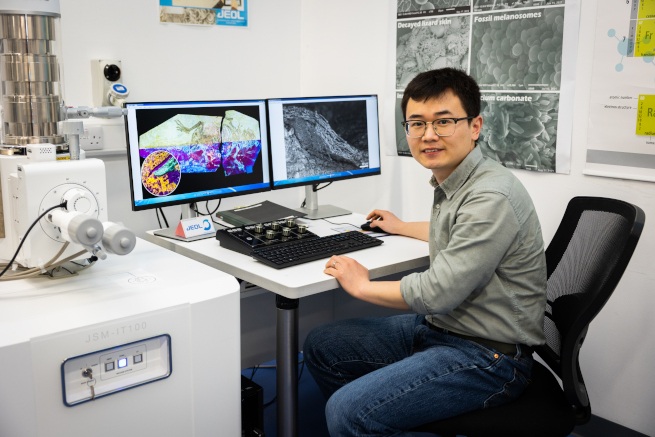

Dr Zixiao Yang. Image: Ruben Tapia/UCC TV

Along with senior author Prof Maria McNamara of UCC and scientists based in Nanjing University, Yang used ultraviolet light to identify patches of preserved skin, which are invisible in natural light.

Further investigation of the fossil skin using X-rays and infrared light revealed what the team described as spectacular details of preserved cellular structure.

“What is really surprising is the chemistry of the fossil skin,” explained Yang, who is one of the study’s authors. “It is composed of silica – the same as glass. This type of preservation has never been found in vertebrate fossils. There are potentially many more fossils with hidden soft tissues awaiting discovery.”

McNamara, who has undertaken similar studies before, said the evolution of feathers from reptilian scales is one of the most profound yet poorly understood events in vertebrate evolution.

“While numerous fossils of feathers have been studied, fossil skin is much more rare,” she explained, adding that the team’s discovery suggests that soft, bird-like skin initially developed only in feathered regions of the body – while the rest of the skin was still scaly, like in modern reptiles.

“This zoned development would have maintained essential skin functions, such as protection against abrasion, dehydration and parasites. The first dinosaur to experiment with feathers could therefore survive and pass down the genes for feathers to their offspring.”

Find out how emerging tech trends are transforming tomorrow with our new podcast, Future Human: The Series. Listen now on Spotify, on Apple or wherever you get your podcasts.