The Asus ROG Swift PG49WCD is a brand-new, super-ultrawide OLED monitor featuring a second-generation QD-OLED panel. We first checked out this monitor at Computex, and it is now poised to become available as a premium gaming monitor for those wanting a 49-inch QD-OLED display.

Similar to the Samsung Odyssey OLED G9, which we have yet to review, the ROG PG49WCD utilizes a cutting-edge QD-OLED panel from Samsung. This panel boasts a resolution of 5120 x 1440 for its 49-inch screen, along with a maximum refresh rate of 144Hz. It also supports adaptive sync technology, boasts impressive 0.03ms response times, and has earned the DisplayHDR True Black 400 certification.

Specs and Design

So there’s a few interesting things right off the bat here: The first is the size. This display has a 32:9 aspect ratio and with its 49-inch diagonal dimension, it equates to having two 27-inch 2560 x 1440 monitors side by side in the one panel.

At around 1.2 meters wide it’s a large display that occupies a lot of desk width, but it isn’t overly tall, offering a similar vertical experience to traditional 27-inch monitors. This type of setup is great for side by side applications and productivity work, as well as immersive gaming as it really envelops your entire horizontal field of view, assisted by the 1800R screen curvature.

I’m personally a fan of ultrawide gaming and love using a 34-inch 21:9 ultrawide as it gives an increased level of immersion relative to a similar 16:9 monitor. 32:9 takes things to the next level, it’s 40 cm wider than previous 21:9 QD-OLED ultrawides, and it feels even more immersive to use.

The downside being that while game support is pretty good these days for ultrawides, 32:9 is less supported than 21:9 and 16:9 so you may run into titles that don’t support this type of format without mods or hacks. But the newer the game you’re playing, the less likely this will be an issue in my experience.

The other interesting aspect is the refresh rate. The Asus variant is limited to just 144Hz, even though the Samsung G9 can reach 240Hz using the same panel, and the upcoming MSI 491C also hits 240Hz.

That’s a pretty significant difference, a 67% higher refresh rate for the currently available Samsung model is certainly noticeable and delivers a greater level of motion clarity and responsiveness. Considering the PG49WCD still seems to be a premium gaming monitor, we can’t be sure why Asus have opted for 144Hz when the option of 240Hz appears to be there for the taking.

The Asus design is similar to other ROG monitors, especially their PG27AQDM 27-inch WOLED variant, just now scaled up to a 49-inch ultrawide format. The panel section is thin – though not as thin as the PG27AQDM – and there’s also a central box on the rear housing all the components.

Most of the external surfaces with the exception of the stand legs and screen are a matte grey plastic, pretty standard stuff, although generally the build quality is good. The rear also features a large ROG logo with RGB LED lighting and the general aesthetic of the monitor is gamery.

The stand isn’t as large as you might expect for a huge 49-inch monitor but the legs still span 65cm in width and while the overall sturdiness is good for a screen of this size, it’s not rock solid. The central stand pillar supports height, swivel and tilt adjustment but I was a little disappointed with the range of height adjustability, the maximum height should be a bit taller in my opinion.

Connectivity

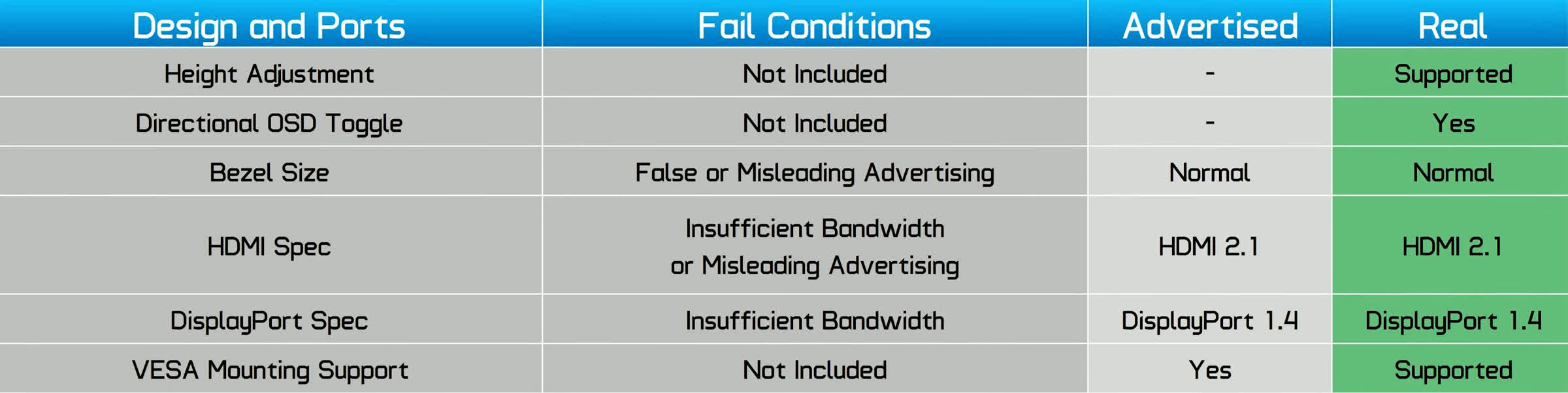

Connectivity is excellent with one DisplayPort 1.4 with DSC, one 48 Gbps HDMI 2.1 port and one USB-C input that does DP-Alt mode and 90W of power delivery, alongside a three port USB hub and even optical audio out. There’s a built-in KVM switch as well for using the display with multiple inputs.

The use of full bandwidth HDMI 2.1 is great and the display supports a variety of input modes including 1440p at 144Hz and 4K at 120Hz, although running an ultrawide OLED with a 16:9 picture for long periods of time may cause uneven wear and the effective burn in of the black bars on either side. So while it does support 16:9 aspect ratio console inputs, it isn’t the most ideal monitor for that use case (outside of occasional use).

The OSD is controlled through a directional toggle along the bottom edge and it packs a great feature set including things like crosshairs, an FPS counter, a sniper mode and shadow boosting. There’s a strong range of color controls and OLED care features as well, including screen shifting, auto-dimming and pixel refresh modes. You can disable DSC if you want to.

Screen Coating, Subpixel Layout and Burn-In

Samsung’s second generation QD-OLED panels do provide some improvements to the issues we highlighted in our initial QD-OLED monitor reviews, chiefly around the subpixel structure. While this QD-OLED panel still uses a triangle RGB layout, the sizing of the subpixels has been adjusted which improves text clarity relative to first-gen QD-OLED. There is still some pink/green fringing at the top and bottom of text, but it’s not quite as noticeable as with first-gen panels.

With those first-gen panels I was one of the reviewers that found the text fringing issue more noticeable and more annoying with desktop app usage; there were certainly others that didn’t think it was a big deal at all. With the second-gen QD-OLED design I think it edges closer into the acceptable range, it’s still not as good as a similar pixel density LCD that uses an RGB-stripe subpixel layout, but typically it’s reasonable enough for occasional desktop app usage and continues to be a non-issue for content consumption like gaming. On top of this, I believe the text clarity of second-gen QD-OLED is much better than similar WOLED panels, so of the two main OLED technologies I would choose QD-OLED for anything text-heavy.

Unfortunately though, the screen composition, layer structure and coating is mostly unchanged relative to first-gen QD-OLED. This second-gen panel is still glossy and still has issues reflecting ambient light when light sources are in front of the display.

The reflection handling itself is reasonable so you won’t always notice those horrible mirror-like reflections in bright usage environments, but the layer structure to this panel still reflects far too much ambient light. If your environment isn’t well optimized, this ambient light reflection makes the panel appear grey even when attempting to display pure black, which reduces the quality of the deep rich blacks that OLED is known for.

So the same thoughts I have in regards to screen composition and coating apply to the PG49WCD as previous QD-OLEDs. In a standard indoor viewing environment with artificial light or plenty of sunlight, QD-OLED isn’t ideal due to its issues with reflecting ambient light and raising blacks.

This ambient reflectivity is exacerbated when there’s more light in front of the panel, but isn’t as problematic when lighting is only behind the display, and it’s a non issue in dimly lit or dark rooms. In contrast, glossy LG WOLED panels typically appear blacker when faced with a bright usage environment as its panel structure rejects more ambient light.

What’s also important to be aware of is that OLEDs generally aren’t great monitors for desktop usage, productivity apps and web browsing because they are susceptible to permanent burn in. Anything with static content like toolbars or icons on screen for a long period of time, like you get with most desktop applications, is at risk of burning in.

Conversely, dynamic content like gaming or watching videos is at practically no risk of burn in, so don’t worry about this if you’re primarily using an OLED for gaming. Even the occasional bit of desktop app usage is fine – it’s more than 8 hours a day of productivity work that may lead to burn in.

As for burn in warranty, unfortunately Asus do not provide specific burn in coverage as part of their warranty. Some QD-OLED models in the past like the Alienware AW3423DW have featured burn in warranties, but Asus are not offering that with the PG49WCD, which is the same policy as with their PG27AQDM. Samsung’s 49-inch OLED doesn’t come with a burn in warranty either.

Response Time Performance

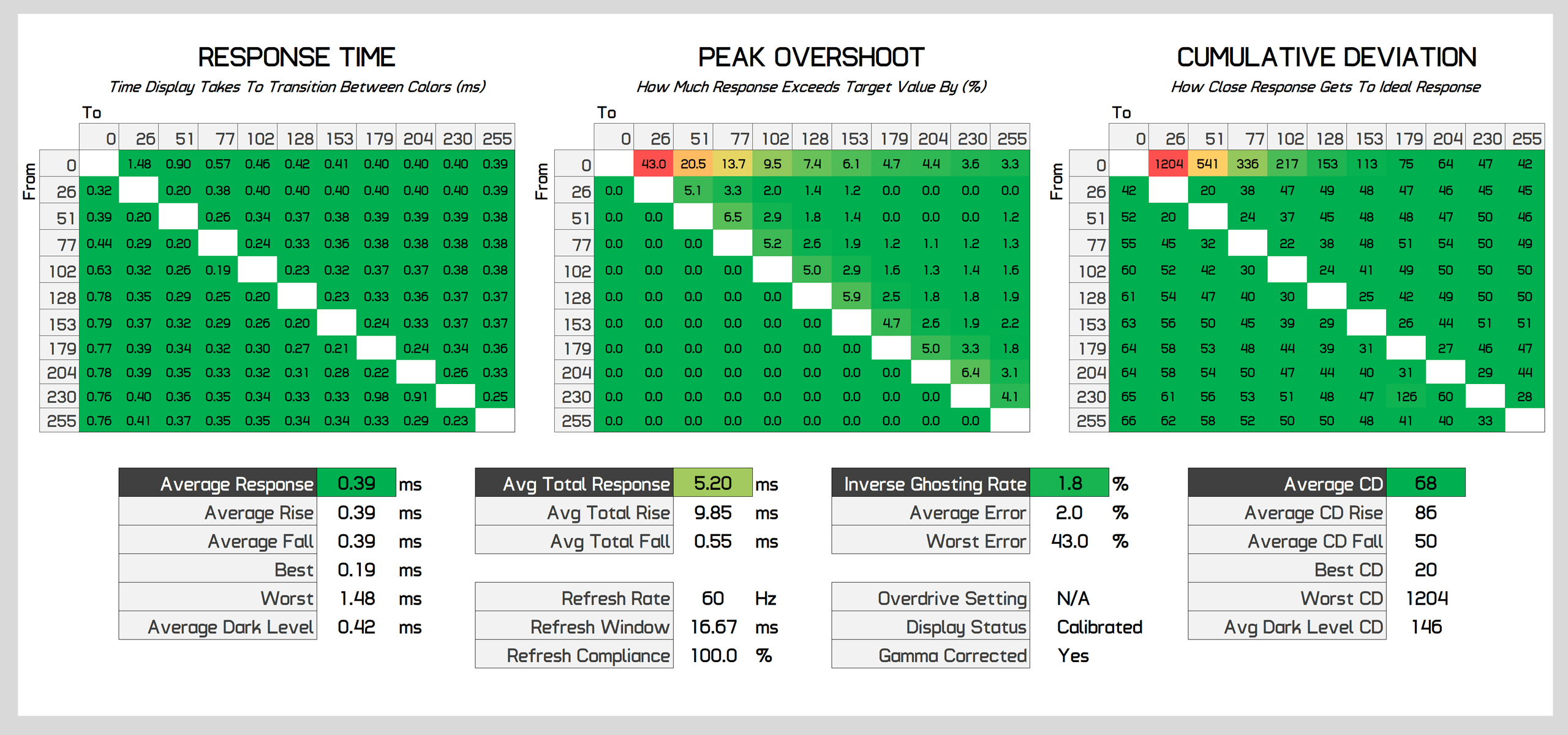

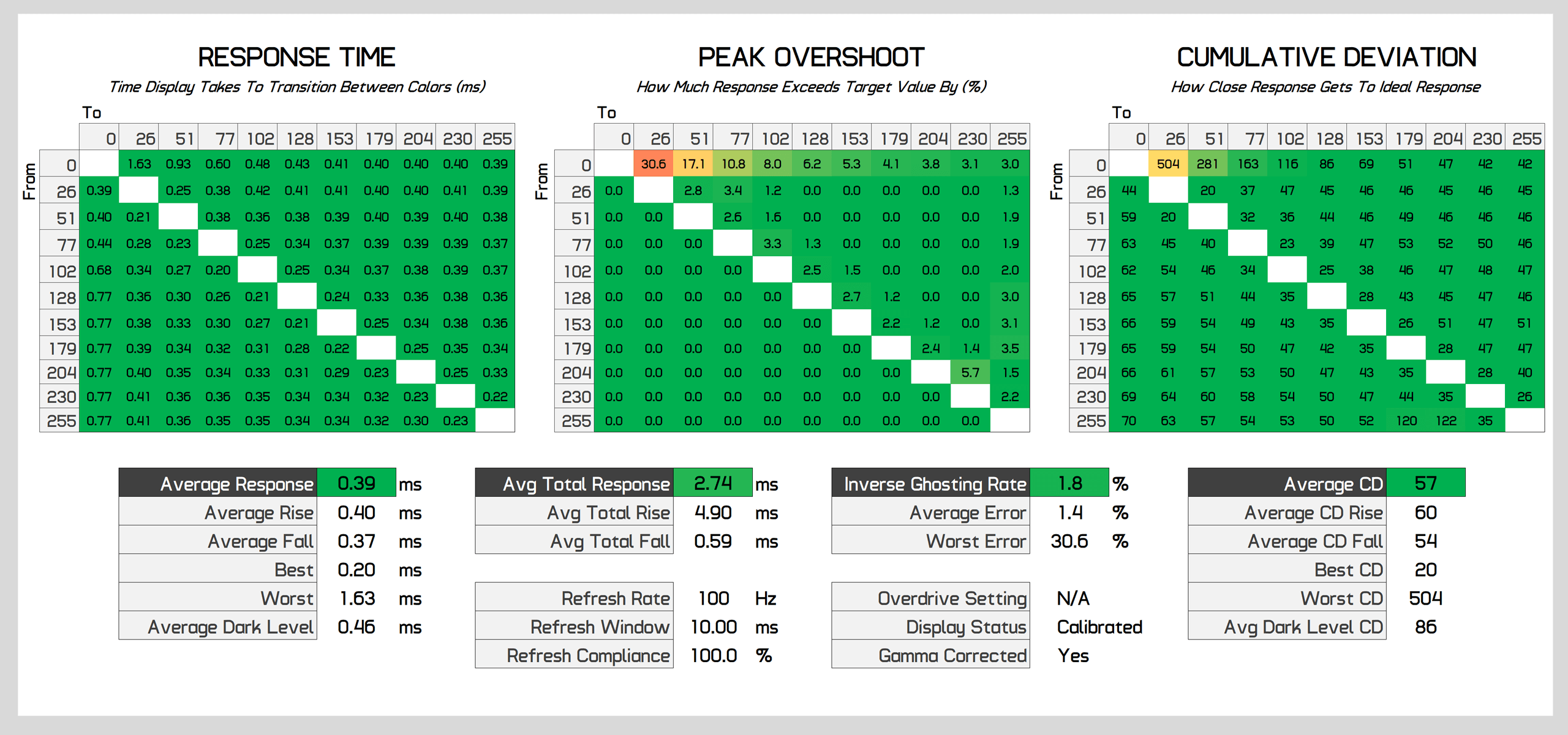

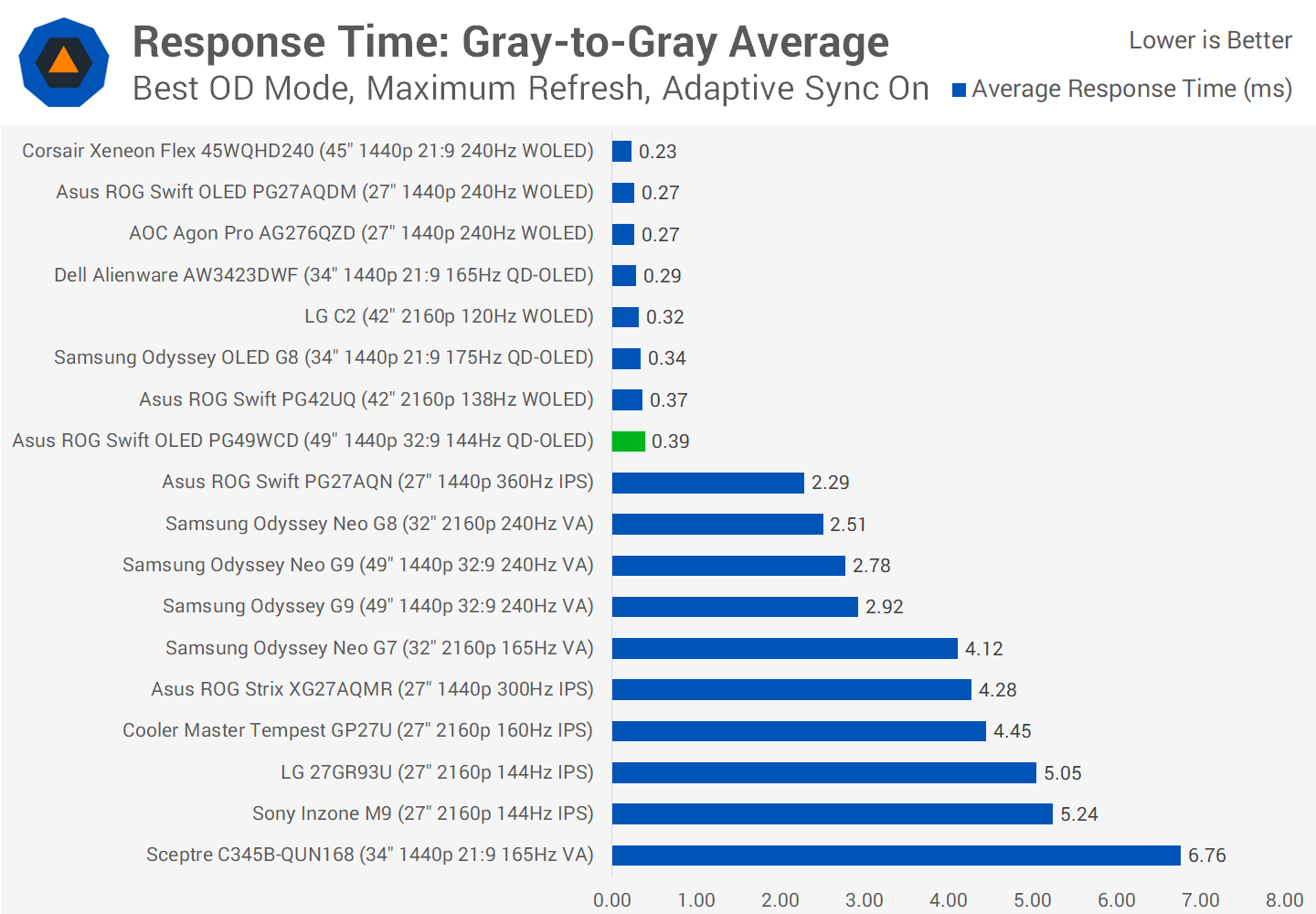

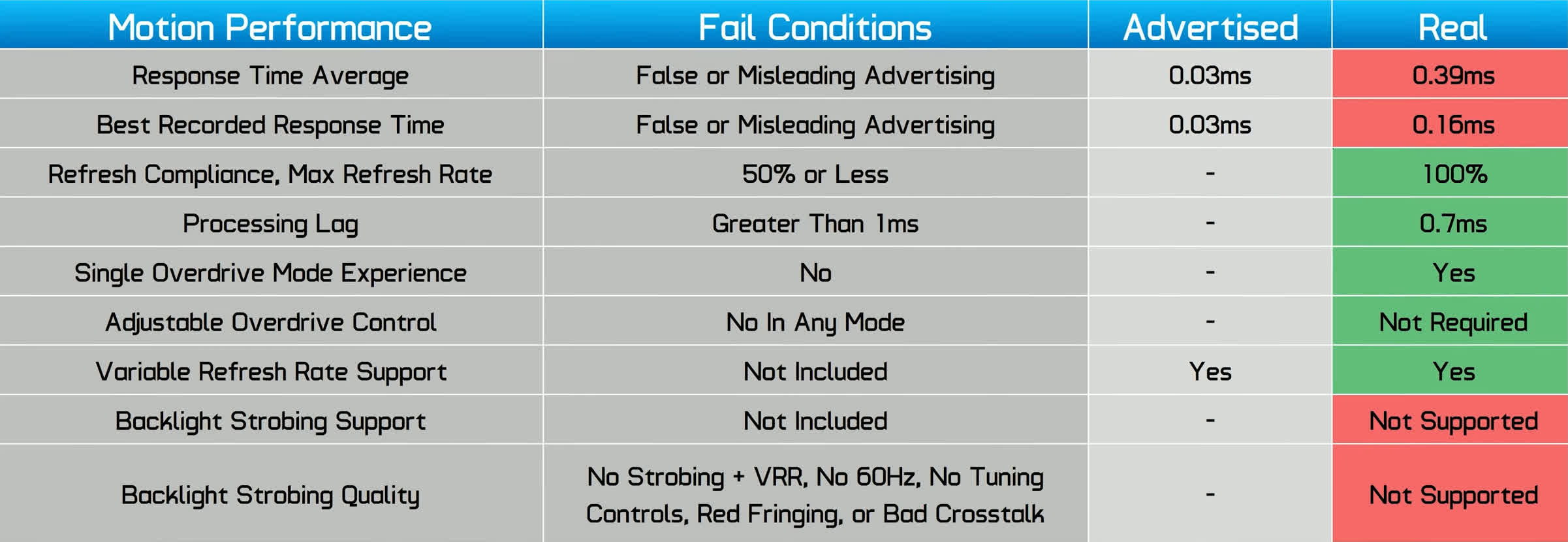

In terms of response time performance, it’s no surprise to see this QD-OLED panel offering lightning fast speeds, similar to other QD-OLEDs we’ve tested. At its maximum 144Hz refresh rate, we’re seeing a 0.4ms average response which is extremely fast and that leads to very clear motion for this sort of refresh rate. With no noticeable inverse ghosting, the Asus model is on par with the other variants for motion clarity, and far superior to any LCD at the same refresh rate. The only downside here is it capping out at 144Hz, instead of 175Hz or 240Hz like we’ve seen from other QD-OLEDs.

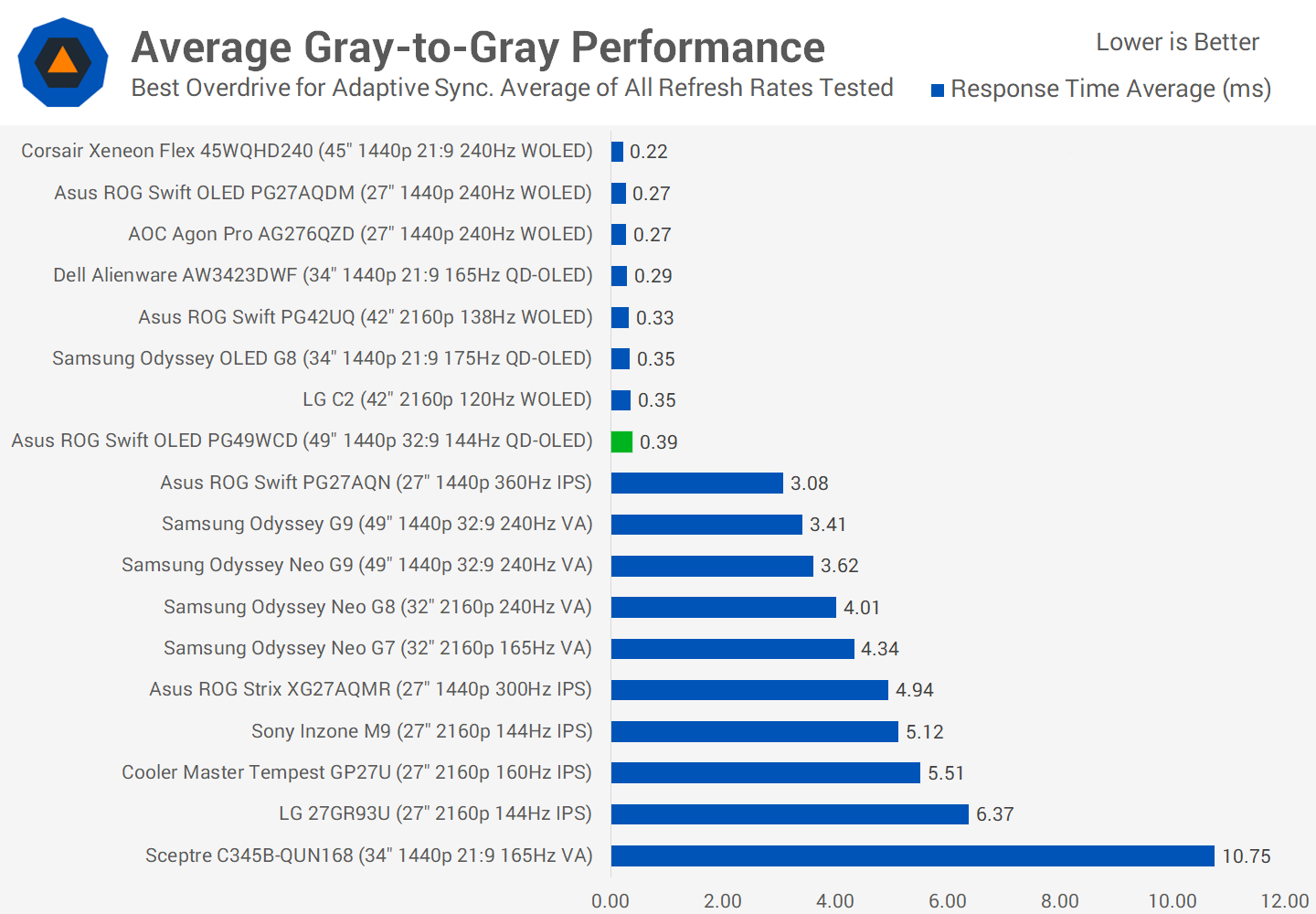

The best part of how OLEDs function is that performance is basically identical at all refresh rates. This means whether we’re testing at 144Hz or 60Hz, we’re still seeing about a 0.4ms response time average. LCDs typically get slower as the refresh rate decreases but this isn’t the case here, so the PG49WCD offers a single overdrive mode experience – without any overdrive settings of course, as they aren’t required for an OLED.

There is effectively no difference in response time performance between this QD-OLED and other OLED monitors. The only difference for motion clarity at the maximum refresh rate is the max refresh itself. The 240Hz monitors in this chart, such as the Asus PG27AQDM, do have superior clarity as there’s less sample and hold motion blur at a higher refresh rate like 240Hz. But as far as response times themselves are concerned, all OLEDs are basically the same.

Where the big difference lies is between OLED and LCD. The ROG Swift is much faster than the fastest LCD I’ve tested, which is a big win for OLED, and it only gets better when looking at average performance. While LCDs do get a bit slower at lower refresh rates, OLEDs don’t, so the gap between OLED and LCD grows. Here the Asus model is around 10x faster than some of the highest end LCDs on the market today.

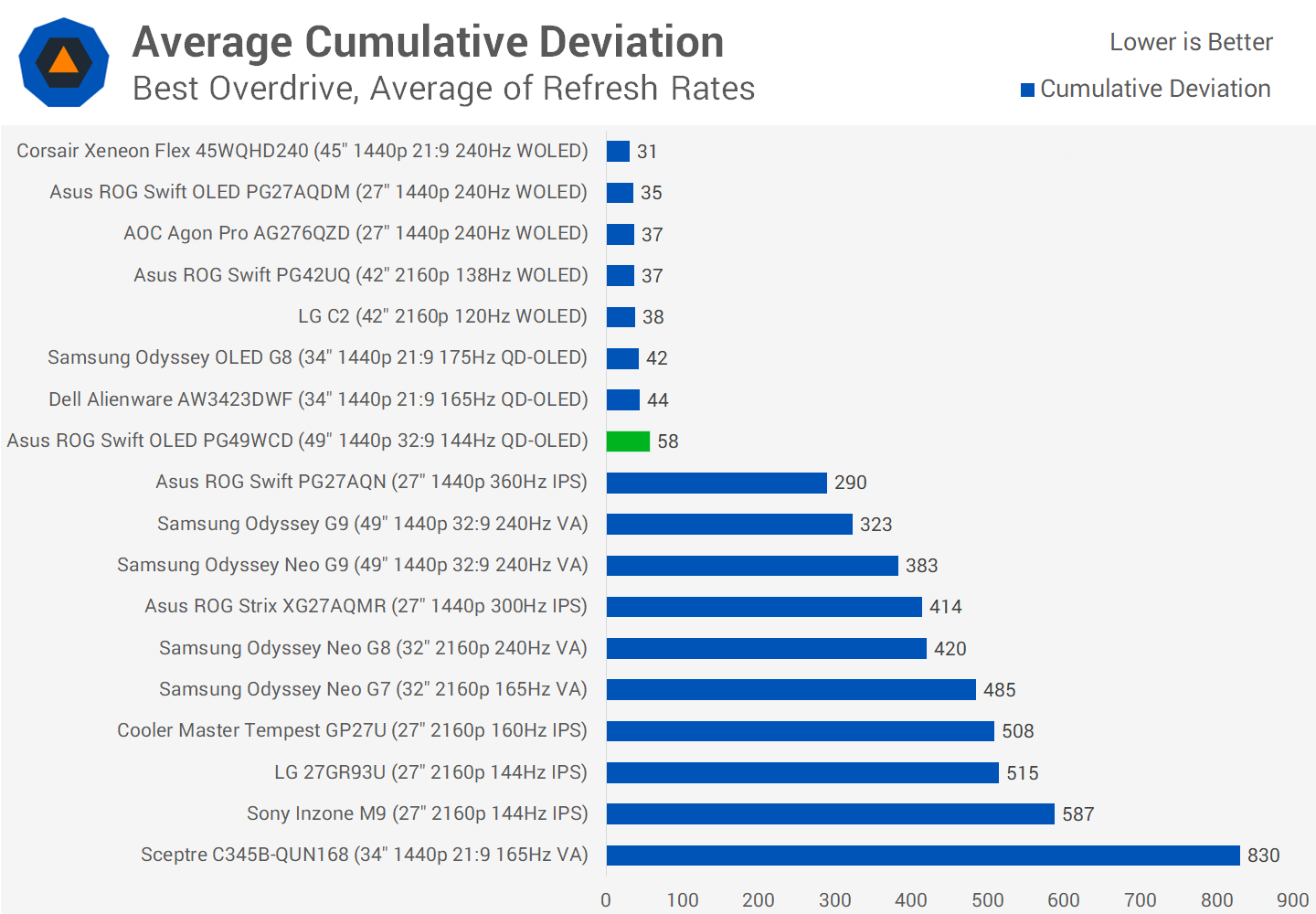

It’s also good to confirm excellent cumulative deviation results, though no different from most other OLEDs. As expected this really is the same technology that delivers the same response time performance as other QD-OLED ultrawides.

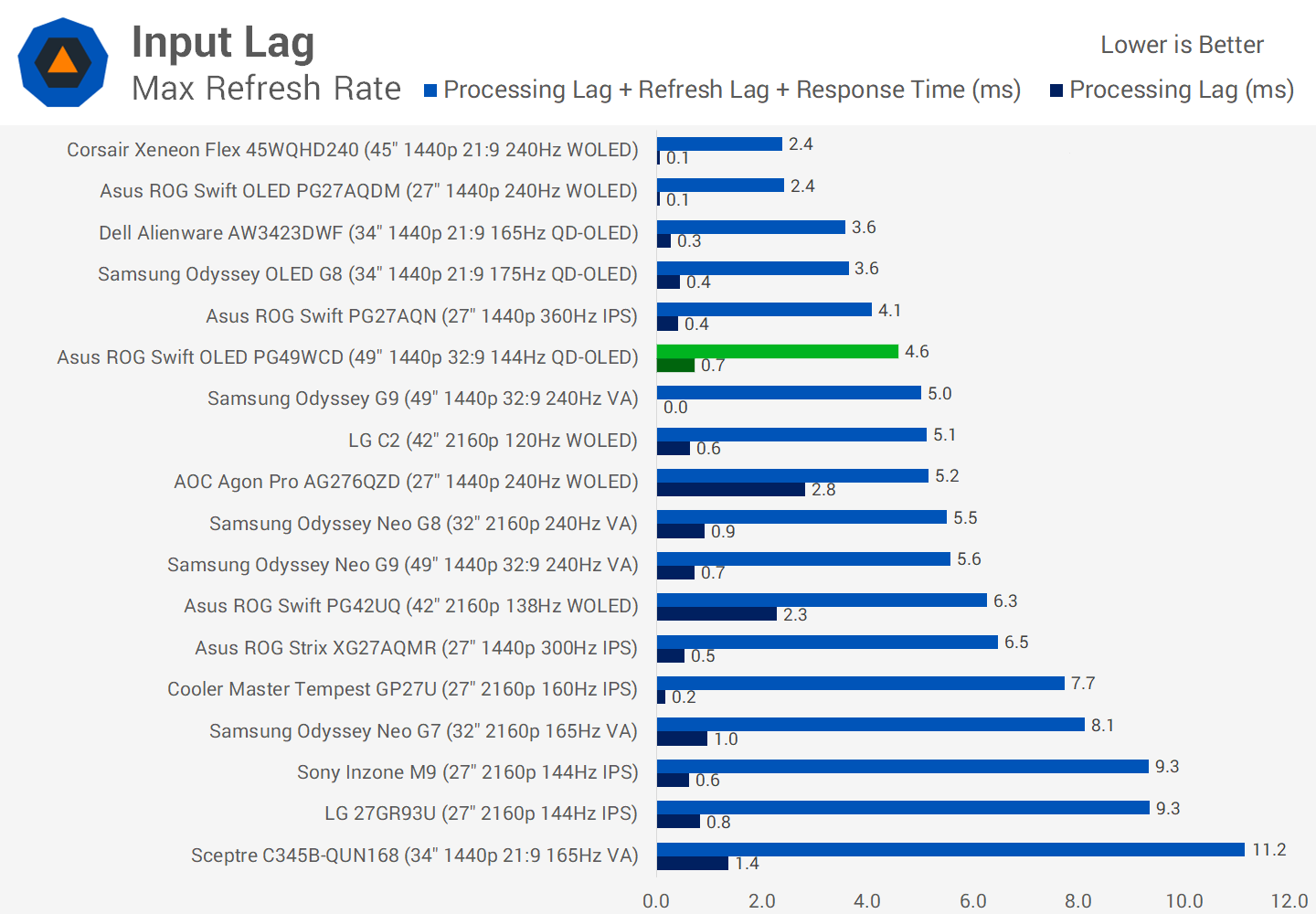

Input latency is great, with Asus delivering less than 1ms of processing delay. Combined with fast response times this generally makes the PG49WCD a responsive monitor, although its refresh rate does limit the input latency relative to higher refresh rate OLEDs. I don’t think competitive gamers would have been overly interested in the format of this display but if you did want something like this for multiplayer gaming then 240Hz would have been ideal.

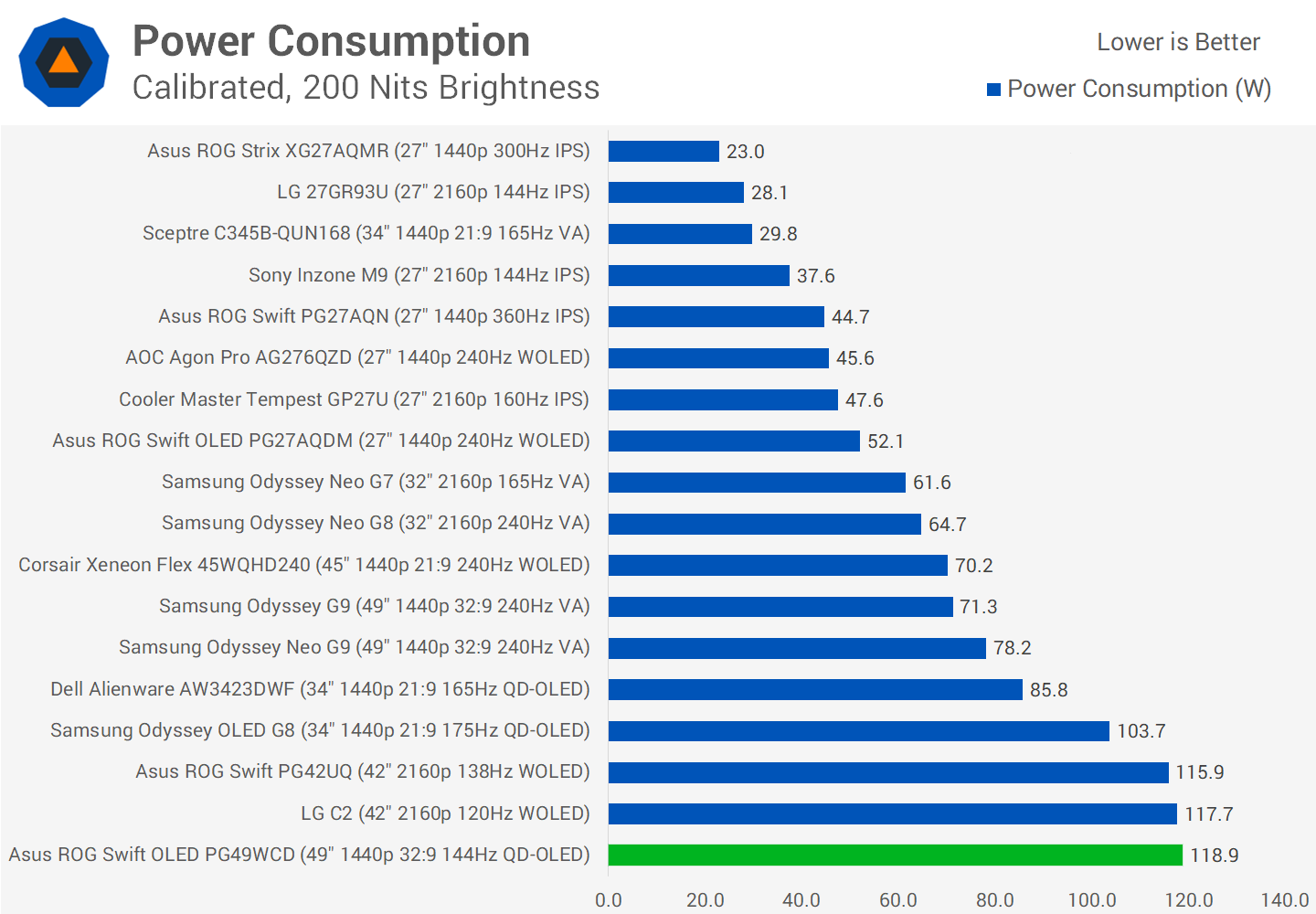

Power consumption displaying a 200 nit full white image is obviously quite high from a large 49-inch monitor, but it’s far from ridiculous given full white is a worst case scenario for OLEDs. 120 watts of usage is similar to the Asus PG42UQ, and 38% more than the Alienware AW3423DWF despite having 52% more screen real estate. Typical usage while SDR gaming is more in the range we see from the Odyssey Neo G9, if not less.

Color Performance

Color Space: Asus ROG Swift OLED PG49WCD – D65-P3

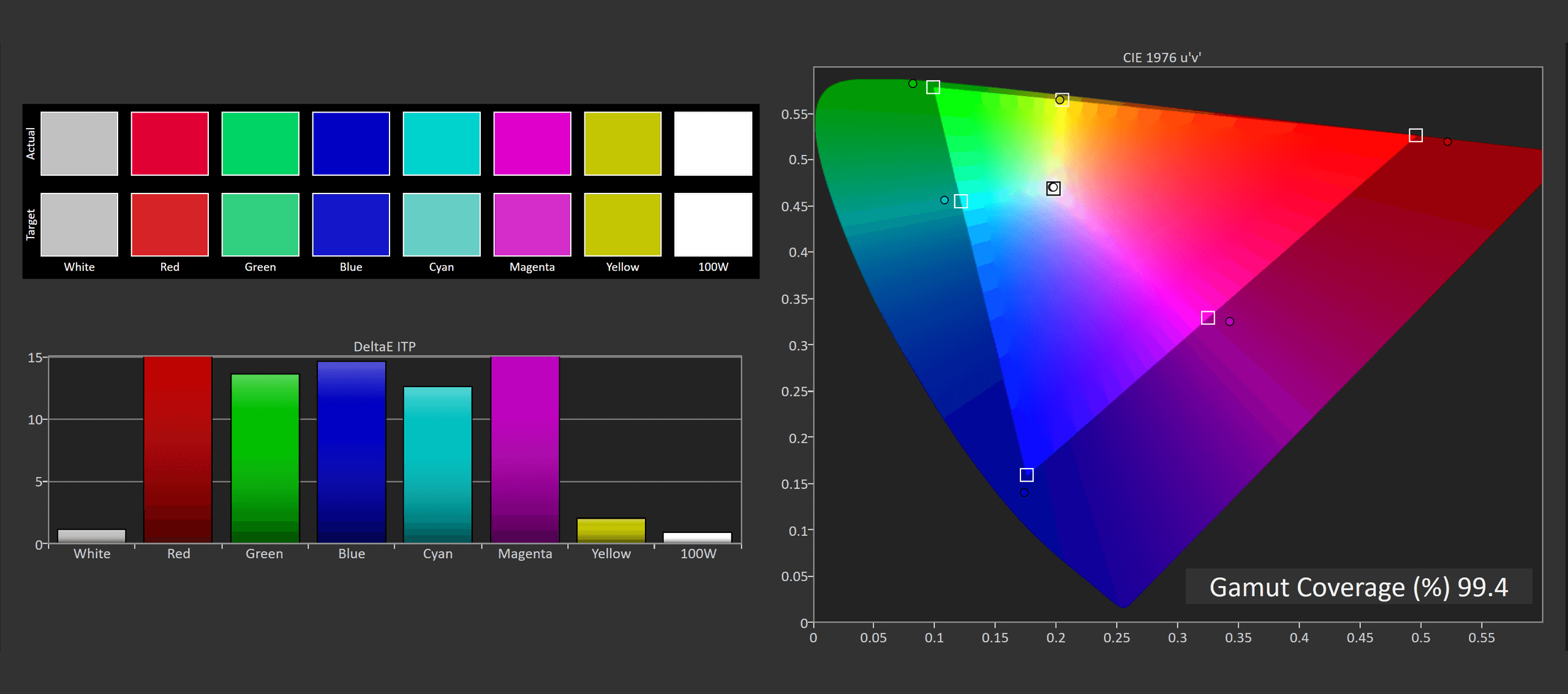

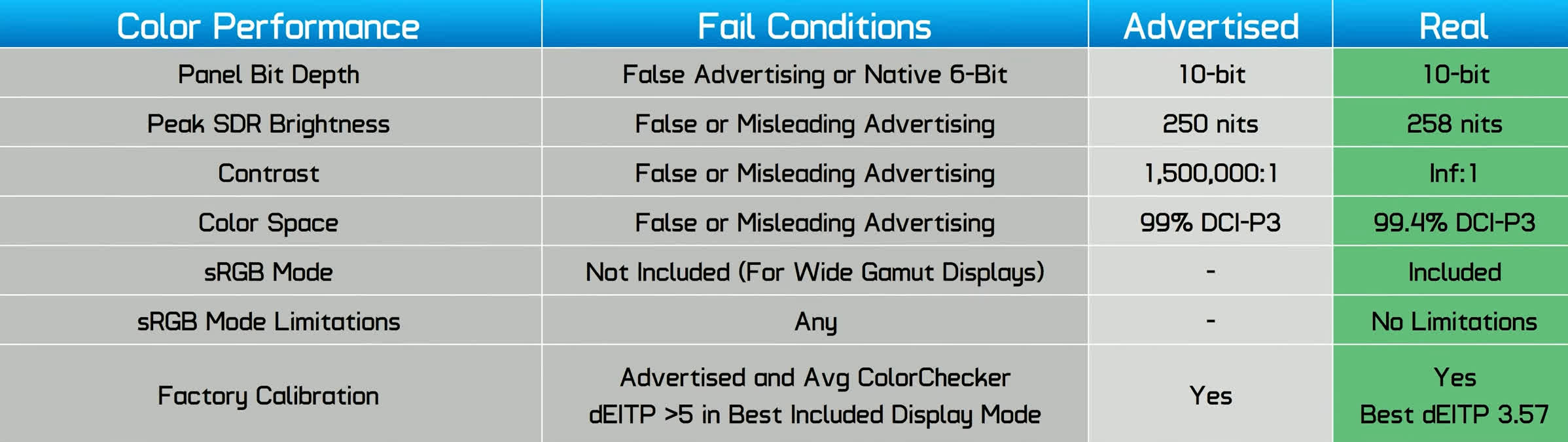

Like other QD-OLED monitors the PG49WCD is a very wide gamut display, sporting 99.4% coverage of DCI-P3 and 98.8% coverage of Adobe RGB, meaning this panel is very well suited to work in either gamut (if it didn’t carry the risk of burn in for productivity tasks like photo editing). In total we get an astonishing 84.4% coverage of Rec. 2020 which is around 4 percentage points better than previous QD-OLED panels, is that the result of the second-generation design? We’ll be able to confirm that with a second monitor using this panel.

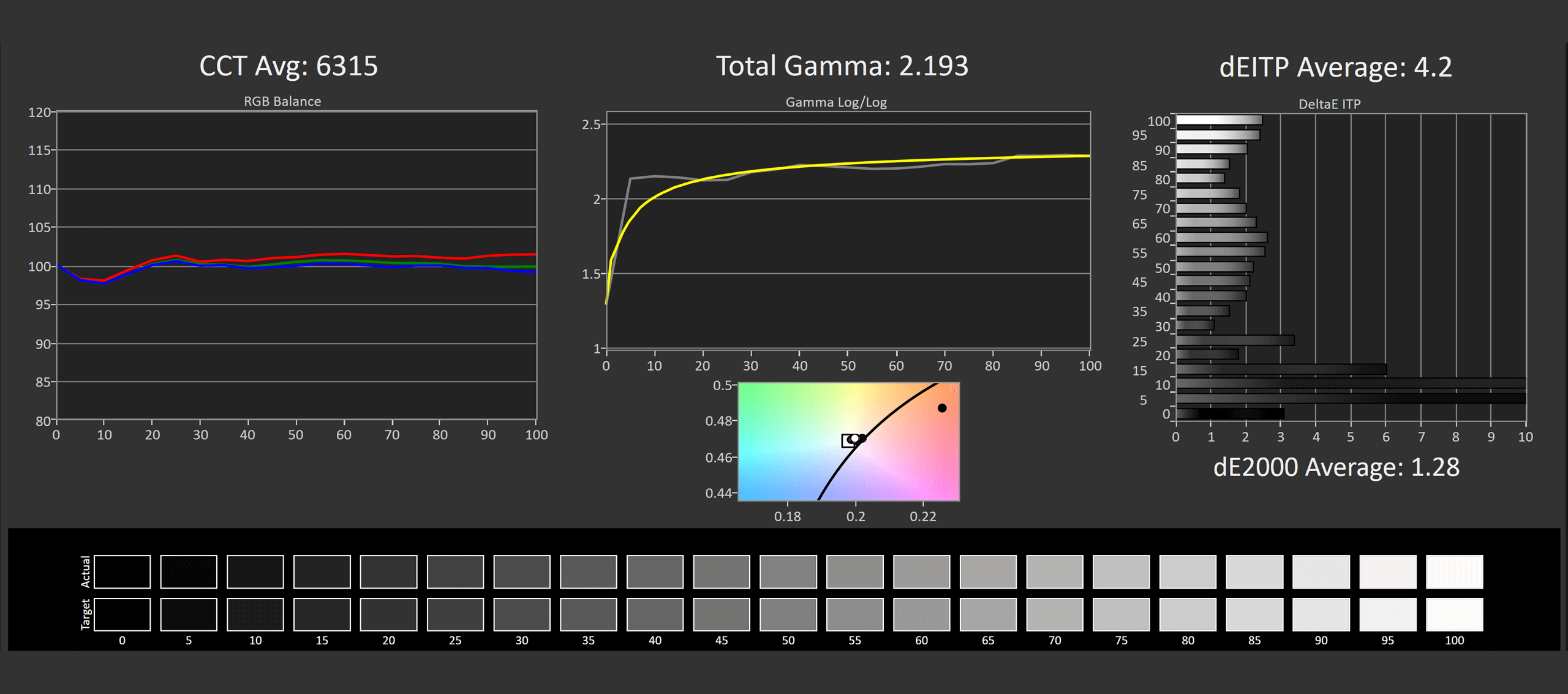

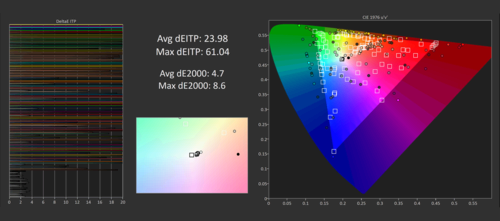

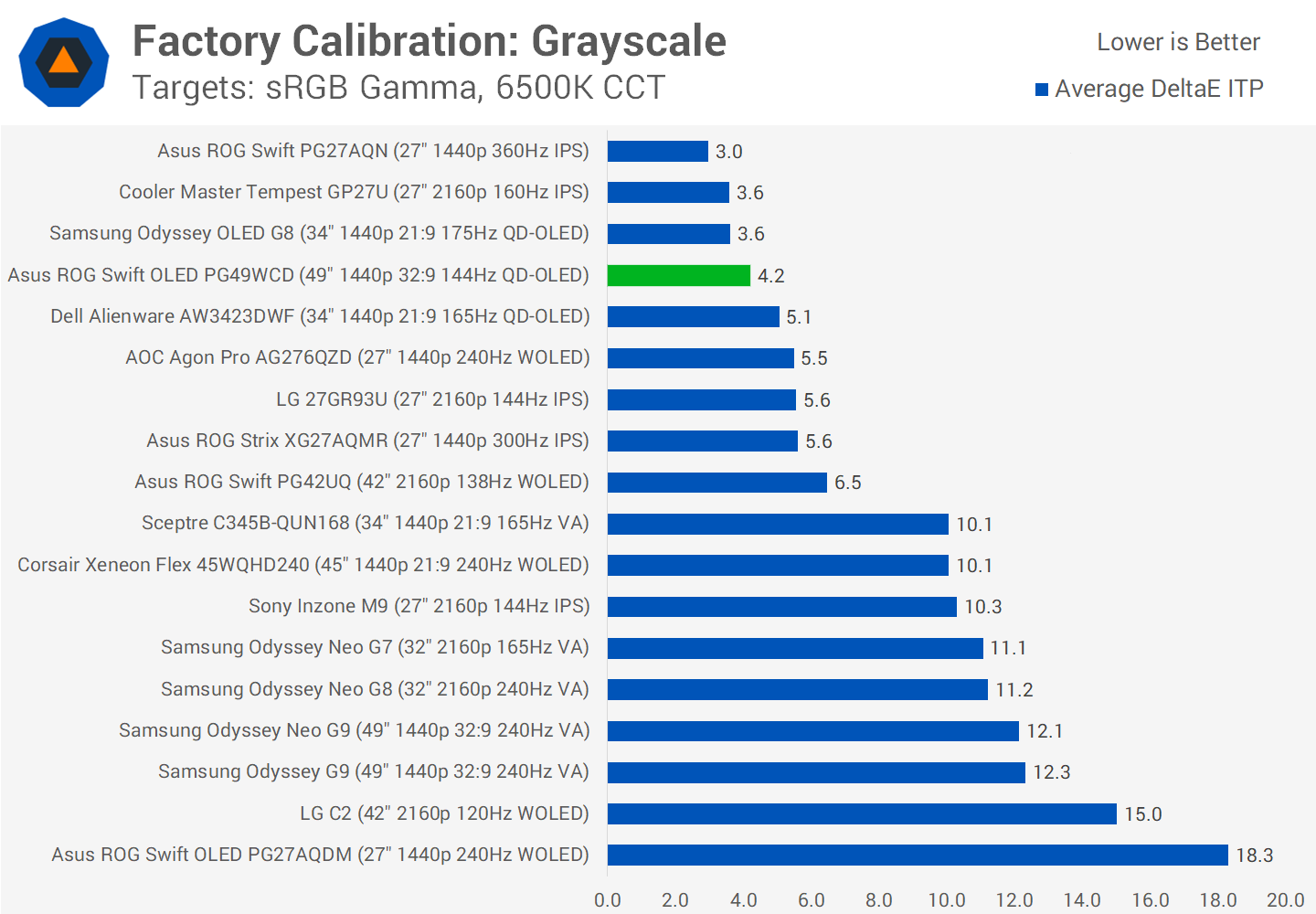

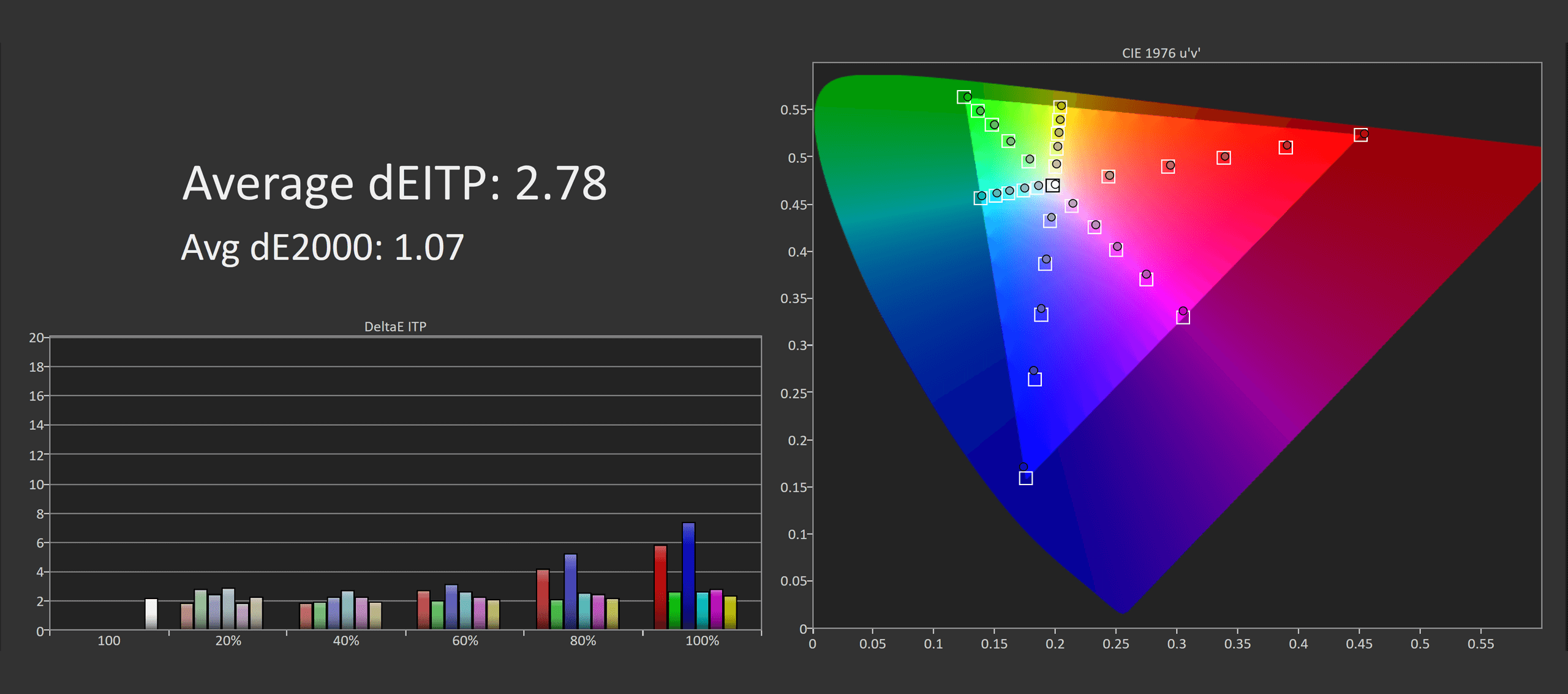

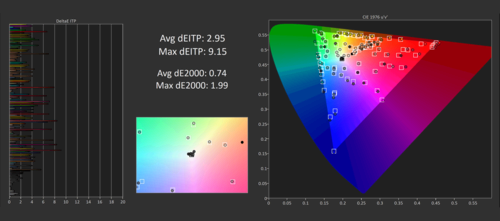

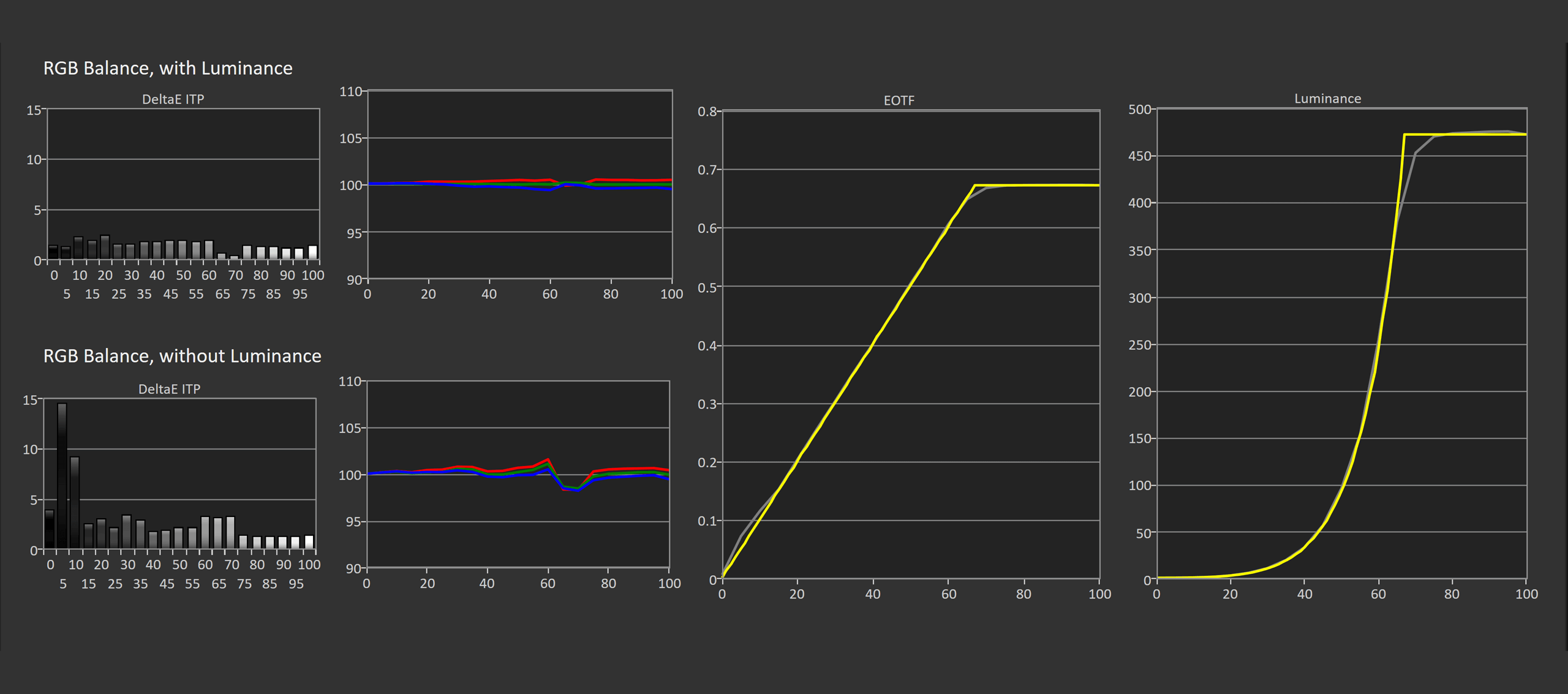

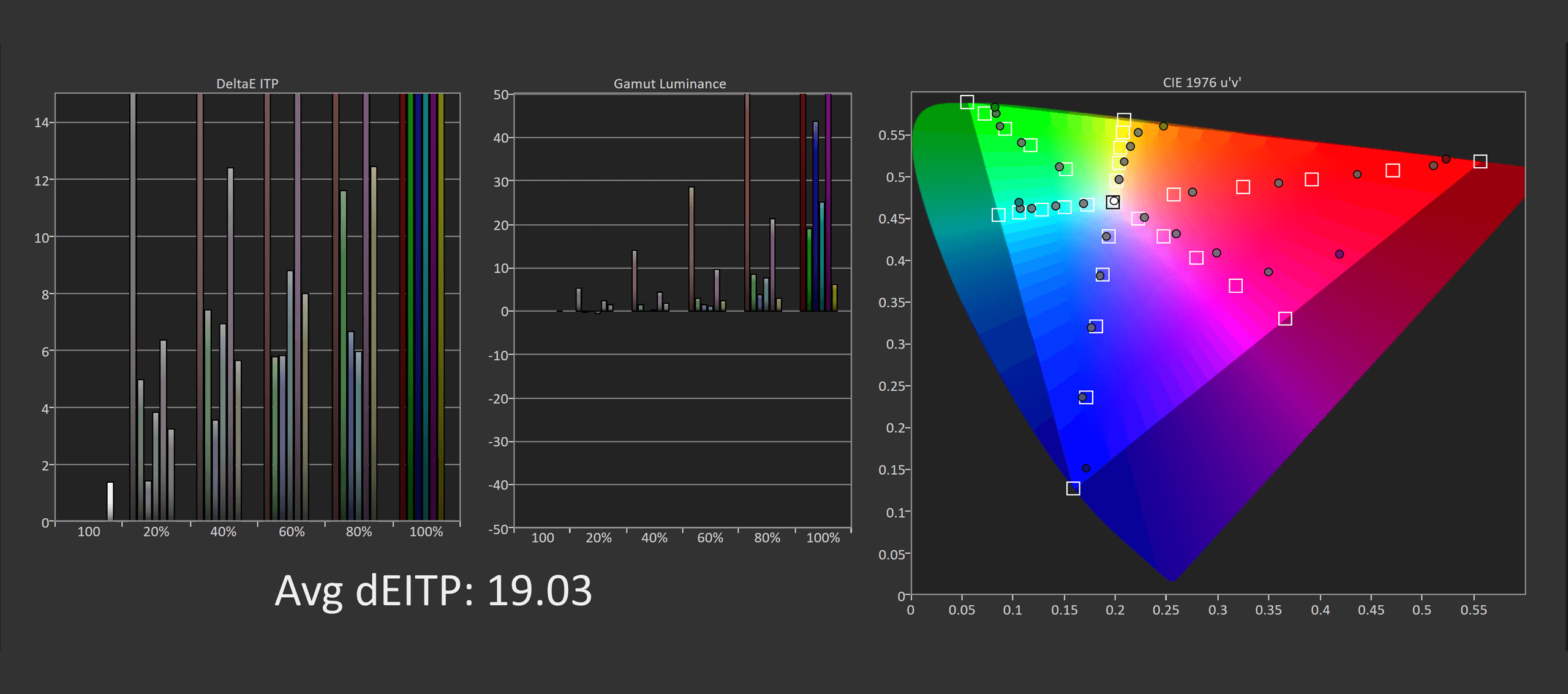

Default Color Performance

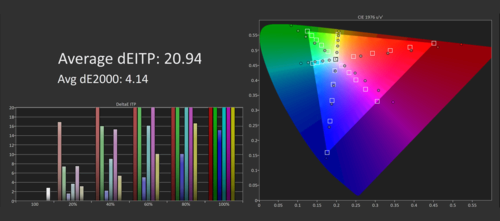

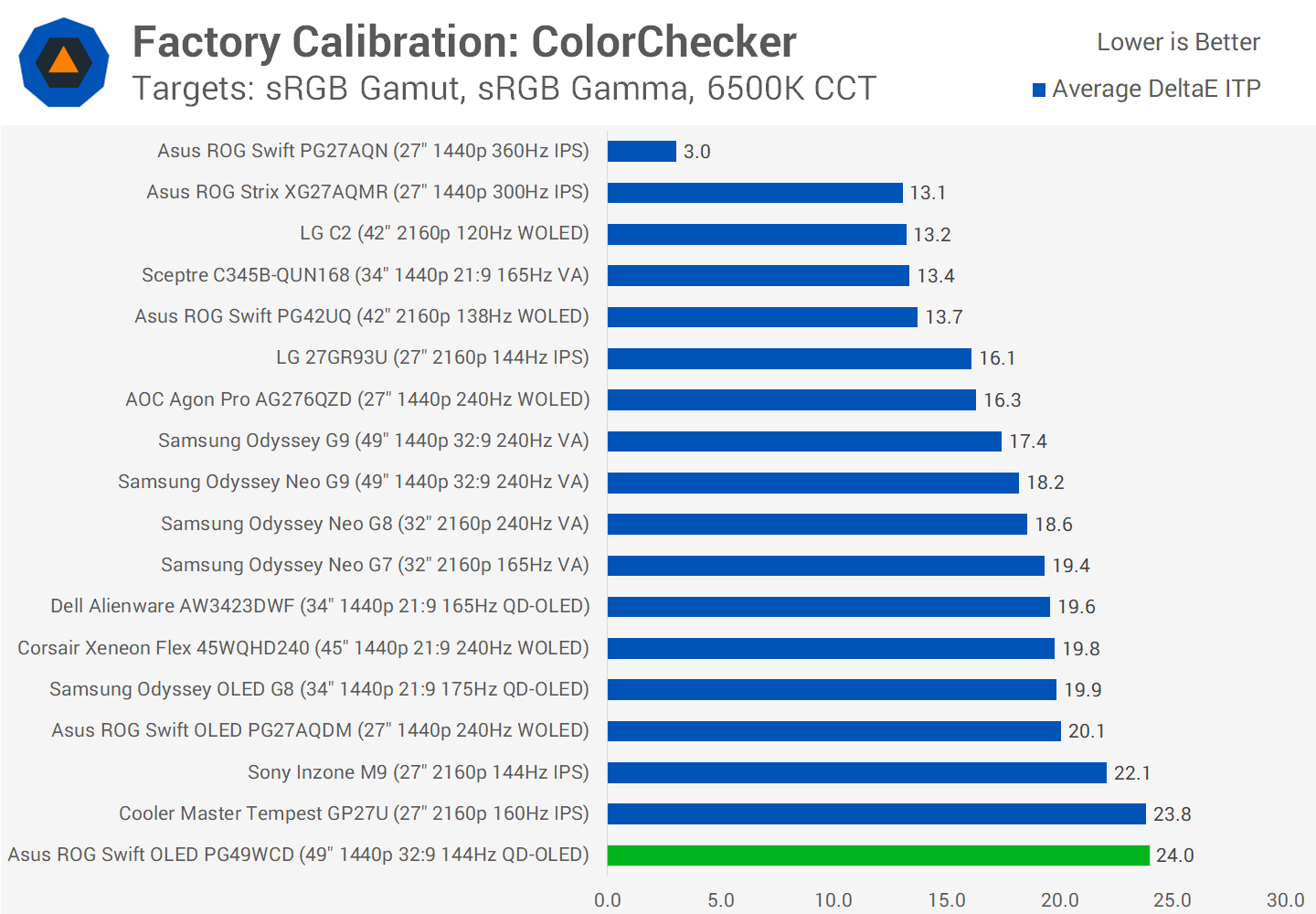

Factory calibration is decent, with Asus producing good greyscale results that show not much color tint and great deltaEs. Some OLEDs have been pushed out with strong blue tints from the factory but this isn’t one of them. However in its default factory configuration, you will see some oversaturation and high deltaEs for ColorChecker as the full very wide gamut is left unclamped. This means that regular SDR sRGB content like desktop apps or YouTube videos gets expanded up into the full gamut, leading to more saturation than is accurate.

Compared to other monitors, factory greyscale performance is great, while ColorChecker performance is not so great. Some nice strengths but also some big weaknesses here.

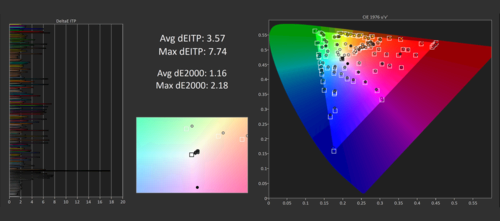

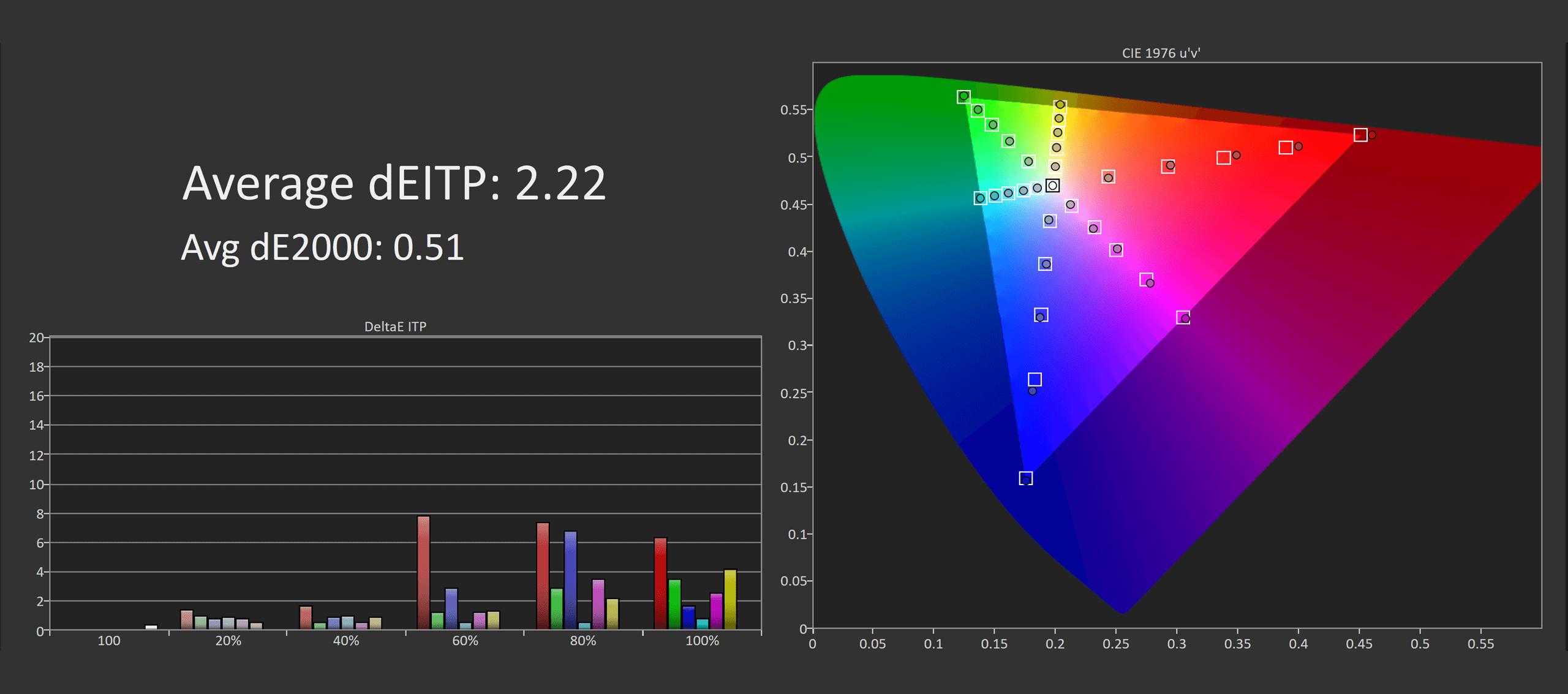

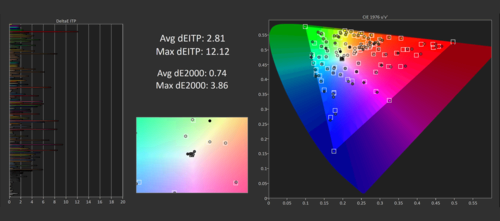

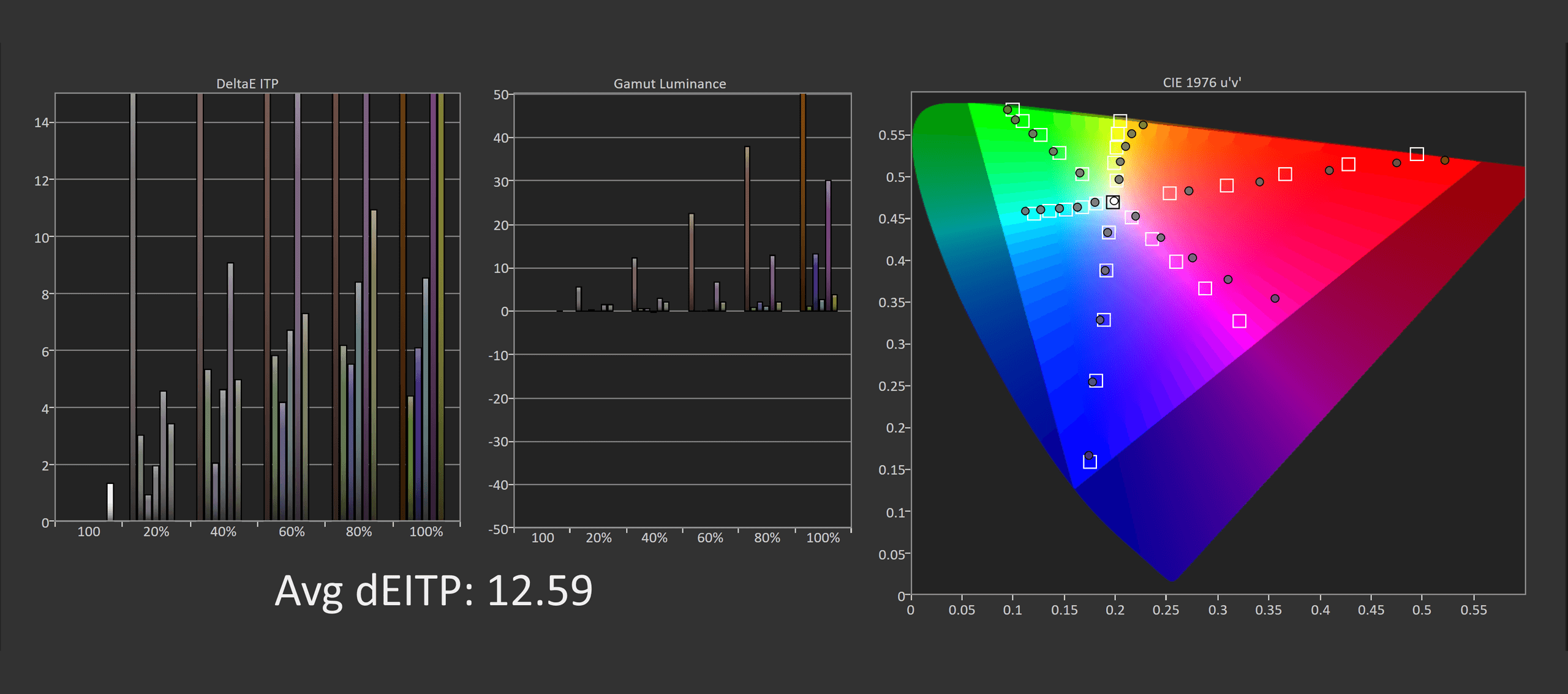

sRGB Mode Color Performance

What is pleasing to see is that the PG49WCD has a good range of calibration controls. You can change the color space to either sRGB, DCI-P3 or wide gamut and it doesn’t lock out any other controls, so you can set the display to emulate the sRGB color space and then adjust white balance and other things. However the DCI-P3 mode seems to just be a copy of sRGB and not actually use the full P3 gamut so that is likely a firmware bug. Alternatively for sRGB color space usage you can use the built in sRGB Calibration Mode which does lock you out of some settings, but is more accurate from the factory, and I’ve been showing you those results right now. With a few simple setting changes like switching into this mode, you can get a nicely calibrated experience with little effort.

Compared to other monitors the sRGB mode is strong for both greyscale and ColorChecker, delivering a satisfying level of accuracy. It’s not far and away better than some other QD-OLED options I’ve reviewed, but Asus have certainly paid attention here to ensure users don’t have to deal with oversaturation if they don’t want to.

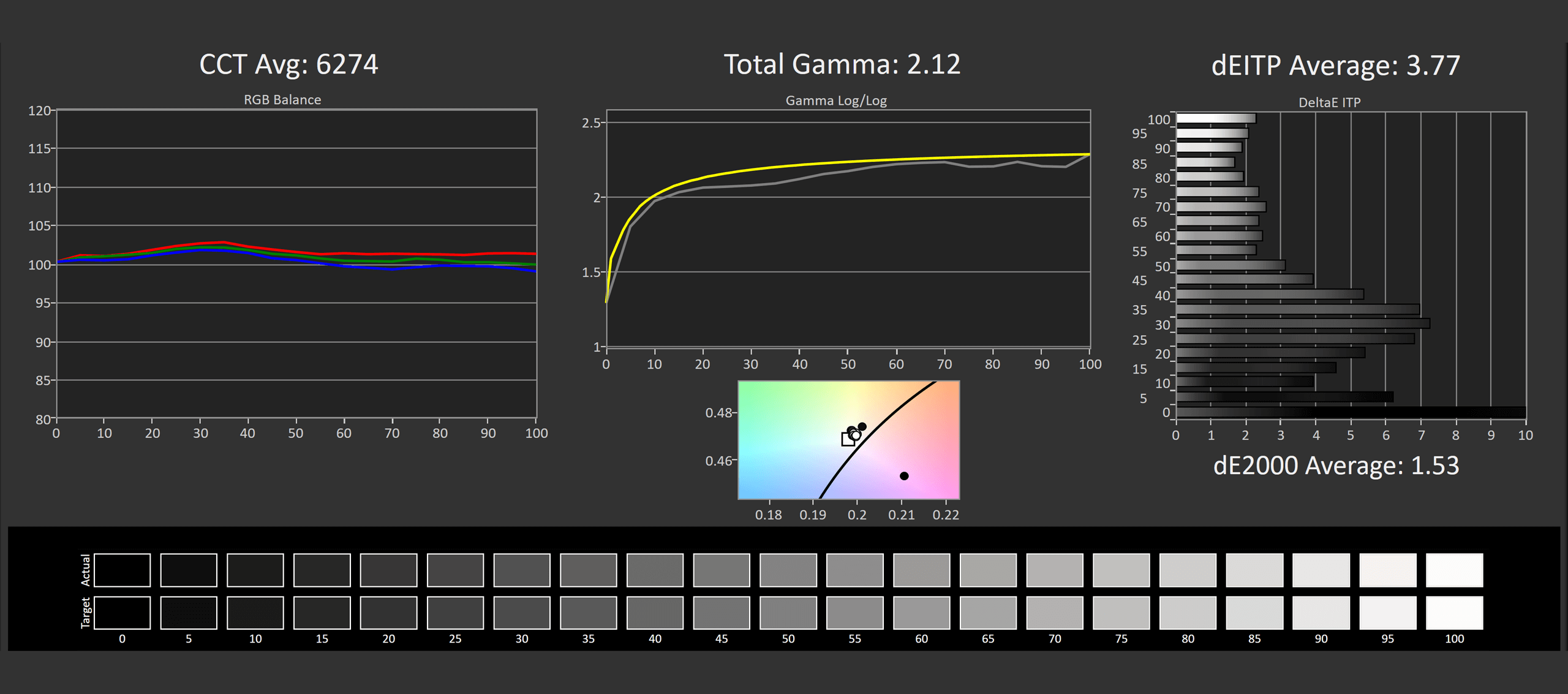

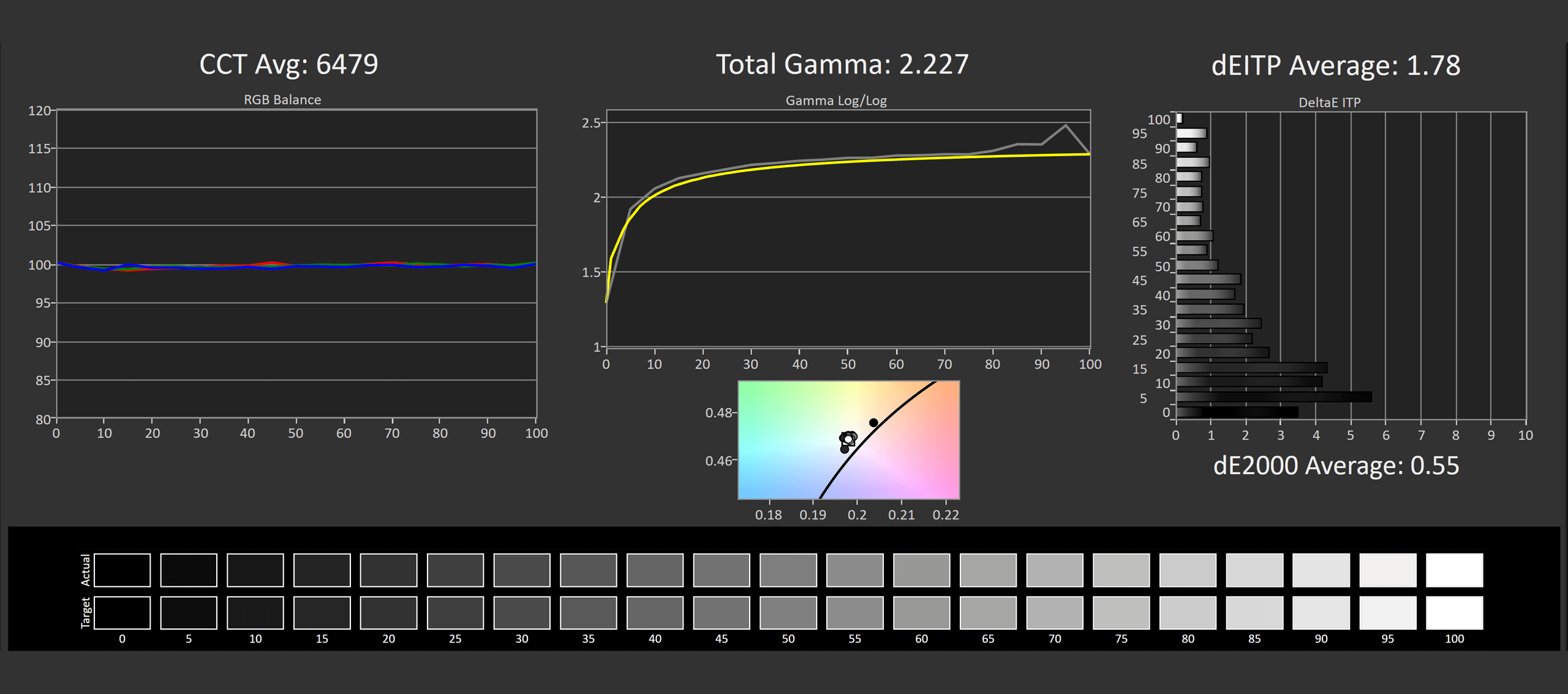

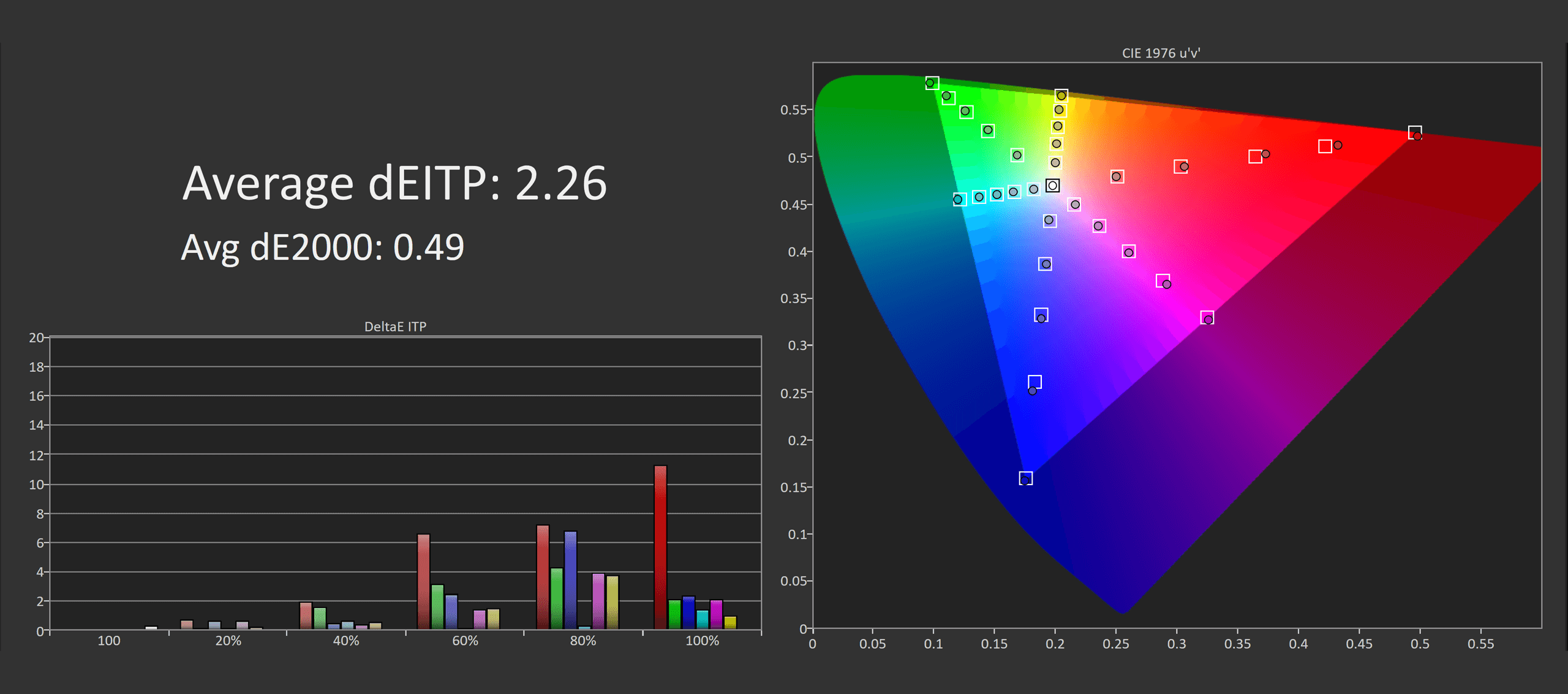

Calibrated Color Performance

Calibrated performance as expected is excellent, and we used Calman for this. The wide color gamut that gives near full coverage of several key color spaces is key to delivering very accurate results most of the time, although the dynamic nature of OLED panels means there is a small amount of variance at times, more than we’d see from an LCD. Nevertheless you can achieve great results on a product like this.

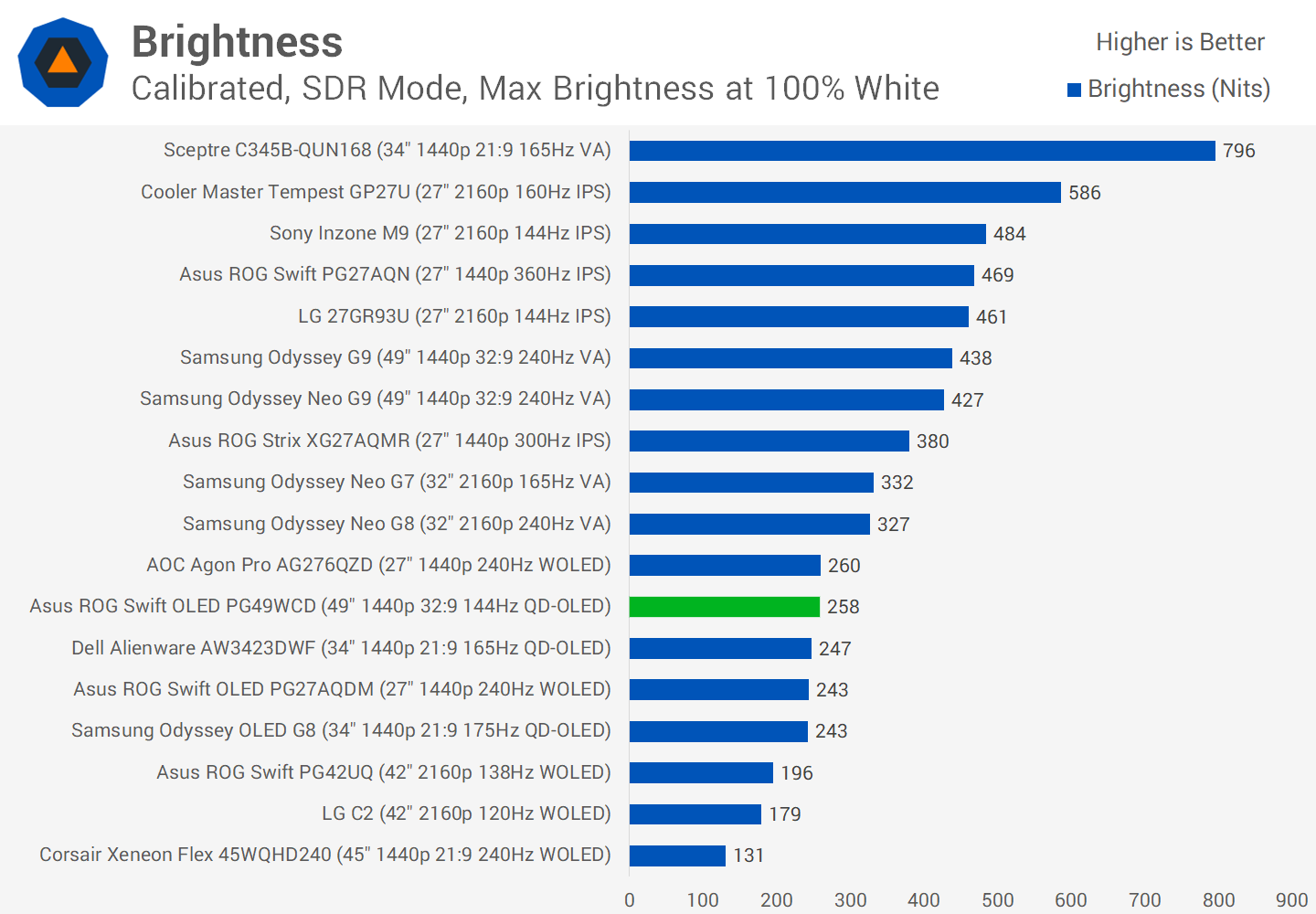

Maximum brightness in the SDR mode is similar to other best in class OLED gaming monitors of today, offering a little over 250 nits, in the same ballpark as all other QD-OLEDs I’ve tested. This is still below most LCD panels, but for indoor usage I tend to think 250 nits is decent enough to be usable. Asus also offer a uniform brightness setting that restricts the panel to 258 nits regardless of window size, which disables the annoying automatic brightness limiter behaviour if you want a nice and consistent experience when using desktop apps. Minimum brightness was also good at 17 nits.

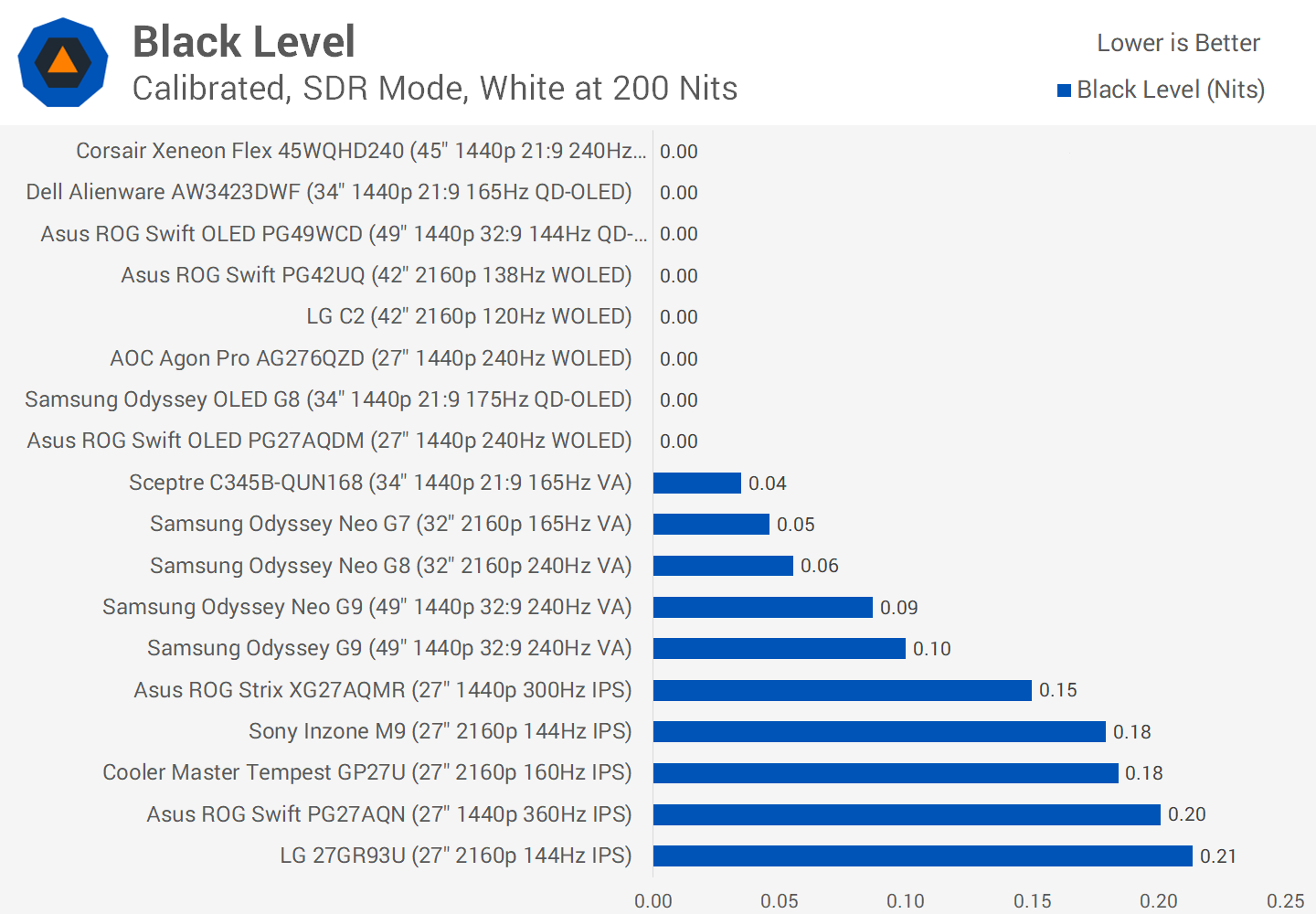

As expected black levels are also practically zero, as each pixel can be fully switched off to show black, leading to an effectively infinite contrast ratio.

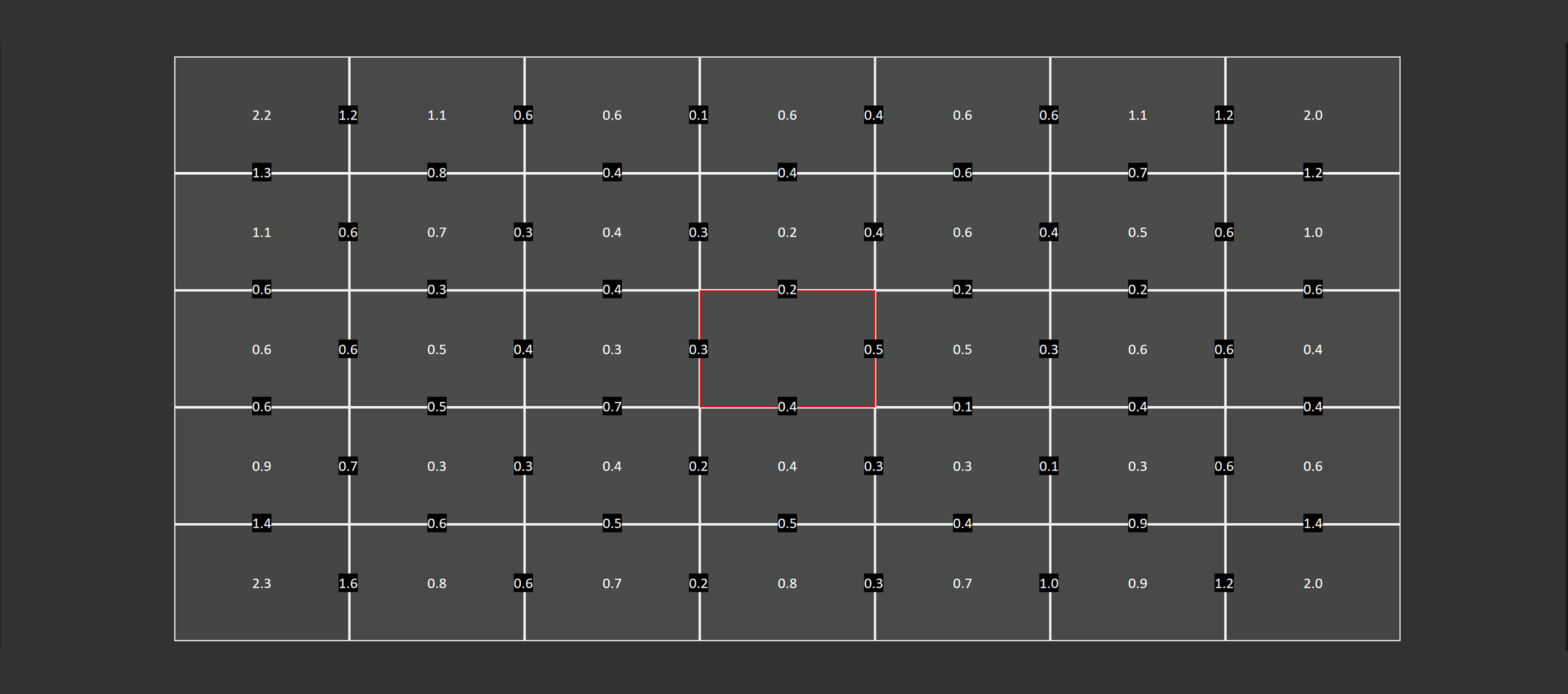

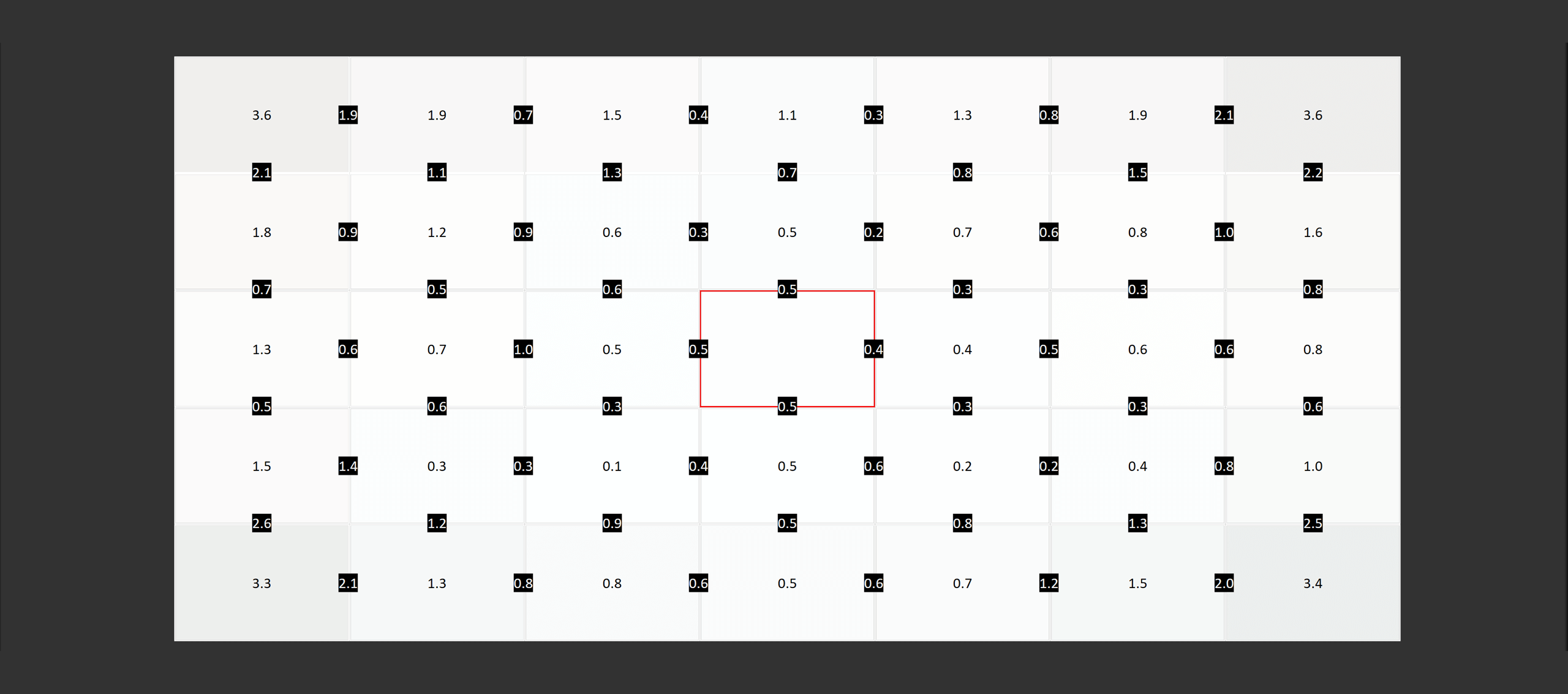

Viewing angles are outstanding from QD-OLED panels, so you won’t have any issues with color shifting or tint when viewed from off angles. The only concern here would be the curve reducing the visibility of the entire screen, though 1800R is good for gaming at this sort of size and ultrawide aspect ratio. Uniformity was great as well, continuing a trend of these QD-OLED panels delivering a nice and consistent experience, the only slight issues we noticed were in the corners but even then it’s hard to notice in practice.

HDR Performance

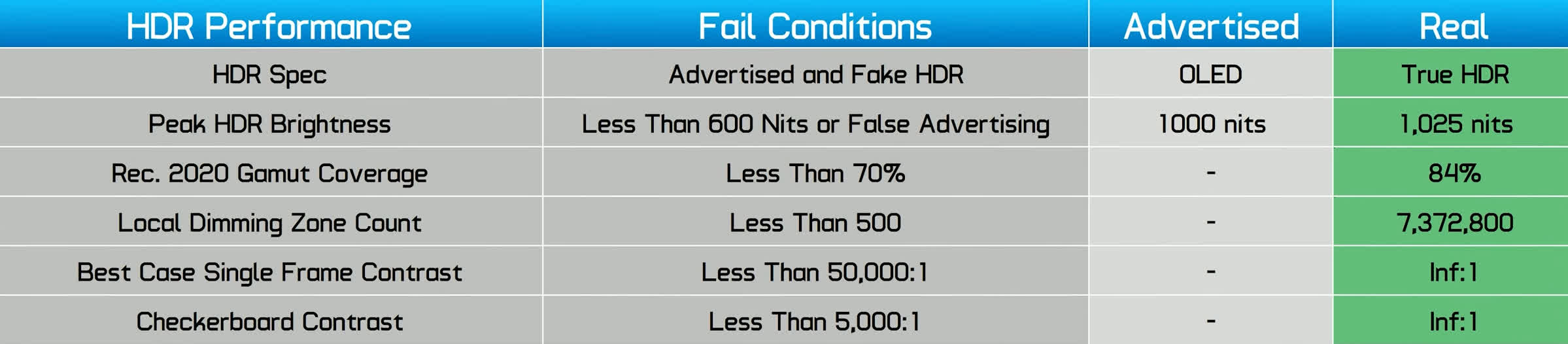

This Asus monitor is a great HDR display. This is due to OLED technology’s inherent hardware qualities that are tailor-made for displaying HDR content. The key feature here is that each individual pixel is self lit, meaning at a pixel level the display can turn on or off to accurately display everything from dark shadows to bright highlights. When the display needs to show pure black, it can fully switch off, giving us the trademark rich zero-level blacks and deep shadows that OLED is known for.

This is in contrast to most HDR capable LCD panels, which are not fully controllable at the pixel level. LCDs require a backlight, and for HDR displays this typically means the use of full array local dimming, a technology that splits the backlight into zones. Whereas OLED can turn off each pixel individually, LCDs with local dimming can only turn off certain zones encompassing hundreds or even thousands of pixels.

This can still be effective for HDR content and look great, but it has some fundamental flaws in difficult circumstances. For example, when showing a bright and dark element close together, an OLED can control each pixel as needed with a clean, accurate distinction between bright and dark. LCDs with local dimming need to masterfully control the zones to achieve the necessary distinction between bright and dark, and when the element is too small or not in the optimal position, the bright element can spill into the dark area within the backlight zone, creating ugly blooming artefacts.

OLED therefore has the edge when it comes to displaying clean HDR content with minimal blooming or haloing. In some scenes this will be the difference between raised blacks and deep blacks, such as for starfields and Christmas lights. At other times, OLED can have a brightness advantage for small bright objects within a dark scene. Subtitles will look cleaner on an OLED with reduced blooming. And generally, OLEDs produce richer shadows thanks to its inherently higher contrast ratio.

Aside from brightness and shadow detail, OLEDs also have other advantages for HDR. As there are no backlight zones, OLEDs are faster to transition between bright and dark with no visible zone transitions. OLEDs are much less likely to suffer from backlight flickering, although light PWM behavior especially when using a variable refresh rate is common. And OLEDs like this one do not increase input latency in its HDR mode, as they don’t need to run a backlight zone algorithm.

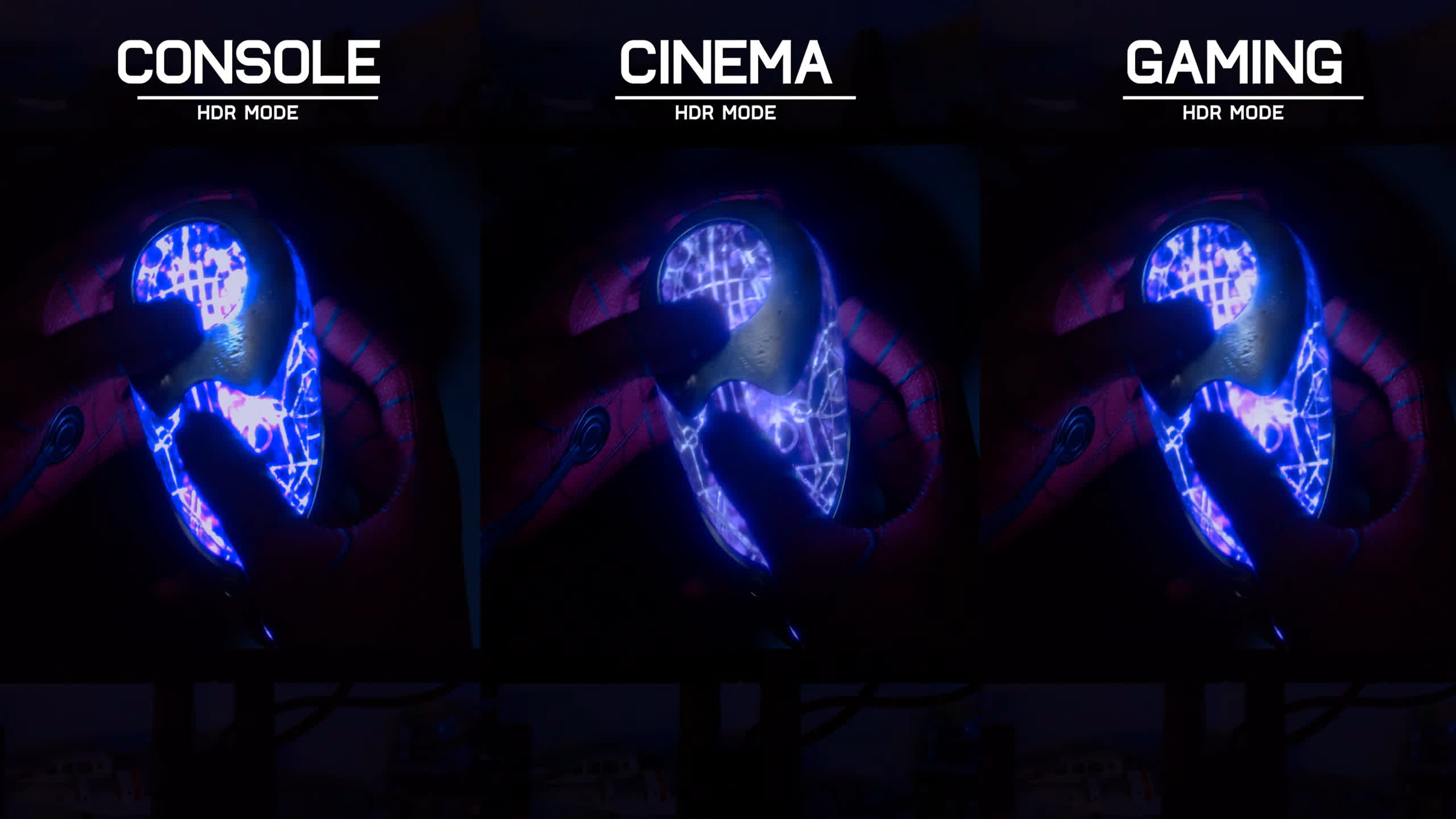

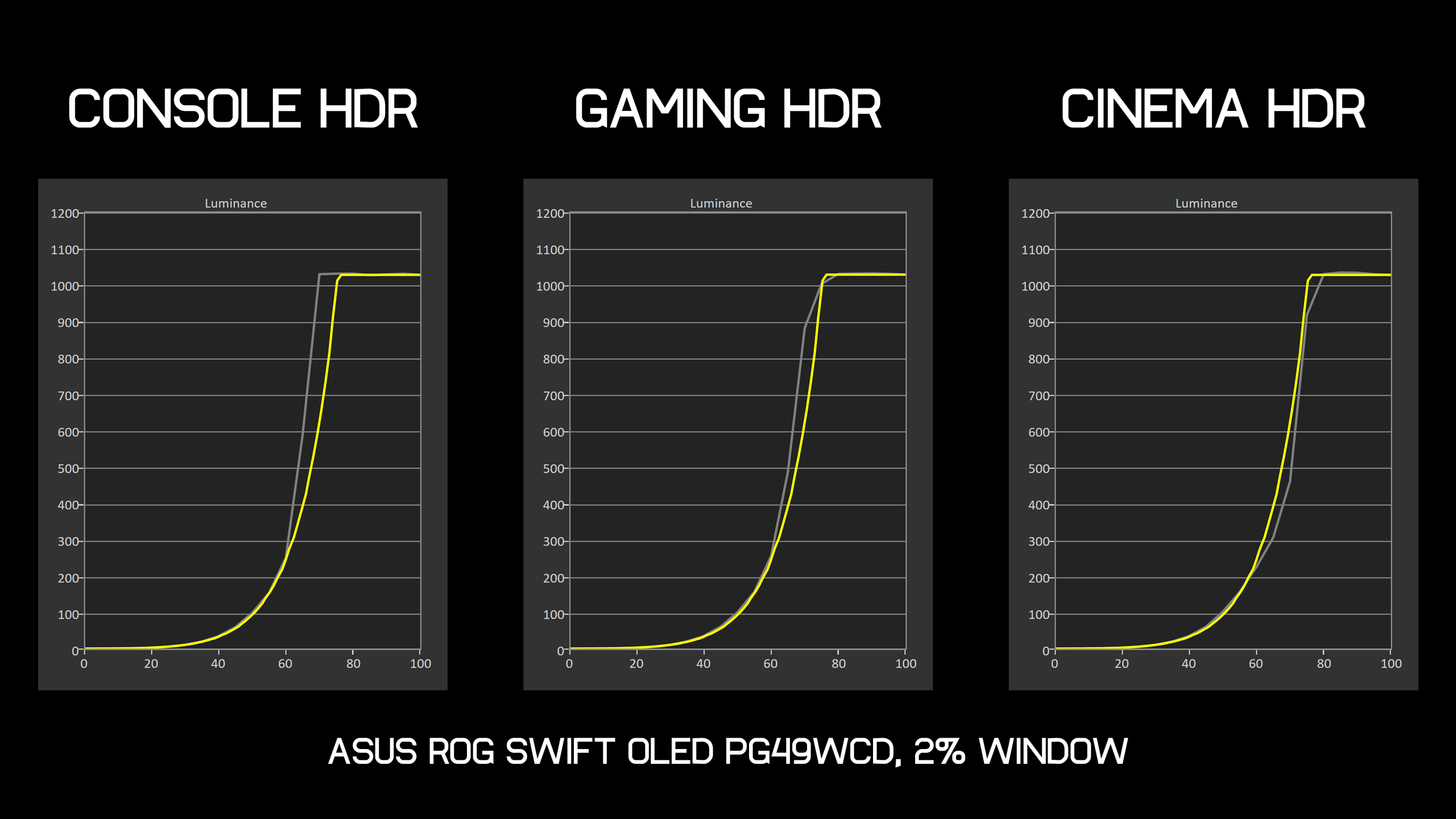

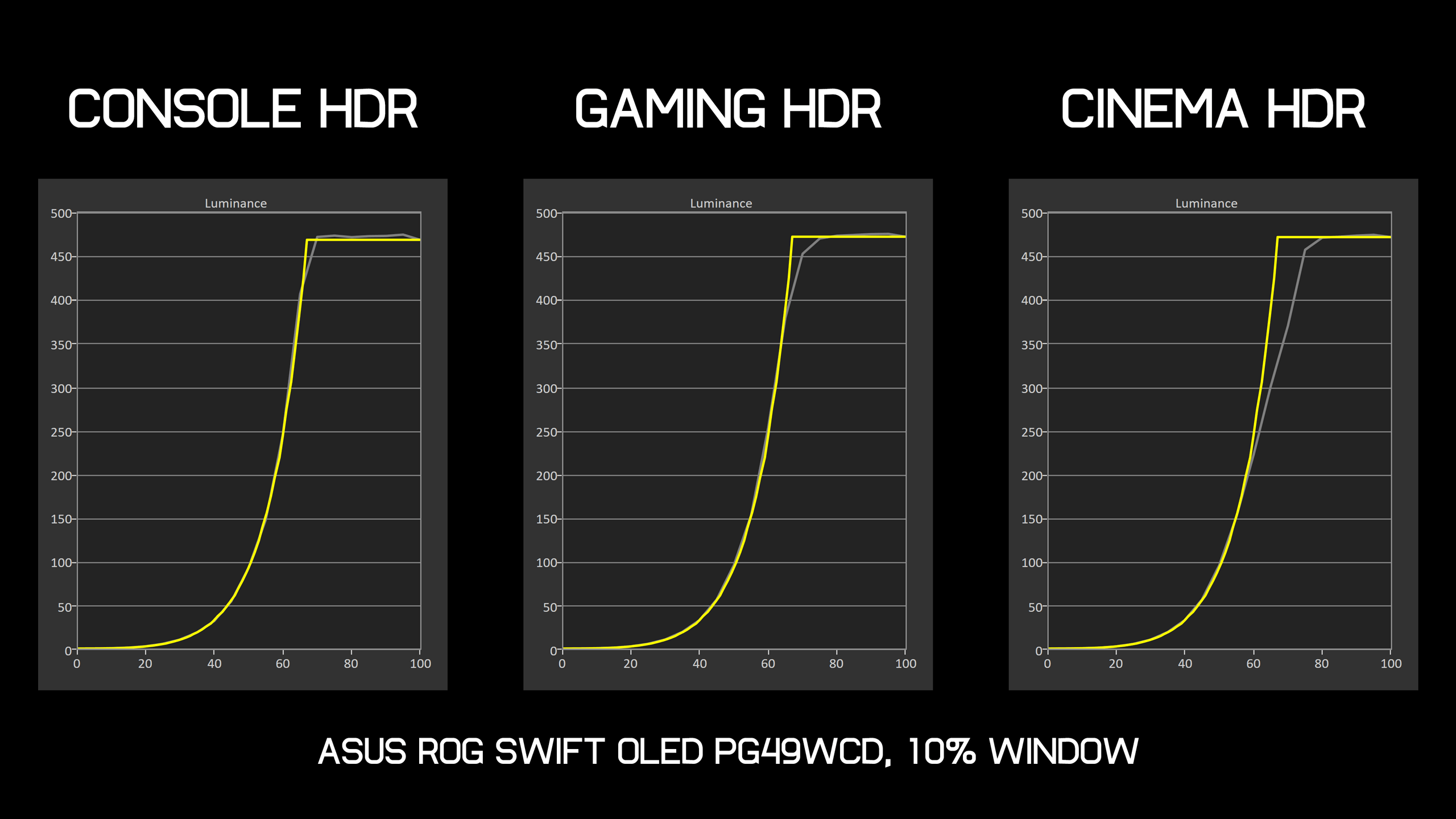

With the PG49WCD there are several HDR modes to choose from, however I noticed fairly early on that the default “console HDR” mode has issues with raised brightness and clipping highlights, leading to weird banding issues and poor color quality. When changing the setting to the Gaming HDR or Cinema HDR setting this issue is greatly reduced without impacting the ability to hit 1000 nits of brightness. The DisplayHDR 400 mode does limit the display to below 500 nits of brightness, so I wouldn’t recommend it.

To see what exactly these modes are doing it’s best to look at EOTF tracking charts. At a 2% window size, which represents small bright highlights, the Console HDR mode hard limits brightness too early, instead of delivering a pleasant fall-off as the capabilities of the display are reached. The Gaming HDR mode is also a bit too bright for these small highlights, but takes a more rounded approach that doesn’t clip as aggressively. Cinema HDR goes the other way and is somewhat not bright enough, though follows the correct EOTF tracking the closest. This performance is identical whether we use an AMD or Nvidia GPU.

What’s frustrating about these settings is that larger window size performance differs. Measuring at a 10% window size in the Console HDR mode delivers very good results and excellent roll-off. The Gaming HDR setting is a bit less close with its fall-off, then the Cinema HDR setting doesn’t get very close at all.

What this all means is that there’s no really accurate HDR mode provided with this monitor. You can choose between the Console HDR mode with terrible highlight performance but better 10% results, the Gaming HDR mode that’s balanced between highlights and 10% but isn’t accurate at either, or the Cinema HDR setting that is very good for highlights but weak at 10%. The ideal mixture would be Console HDR for higher APL and Cinema HDR for lower APL, but we just don’t get that. So I believe the Gaming HDR mode is the best to use as it kinda balances out the experience and doesn’t produce those obviously blown out highlights.

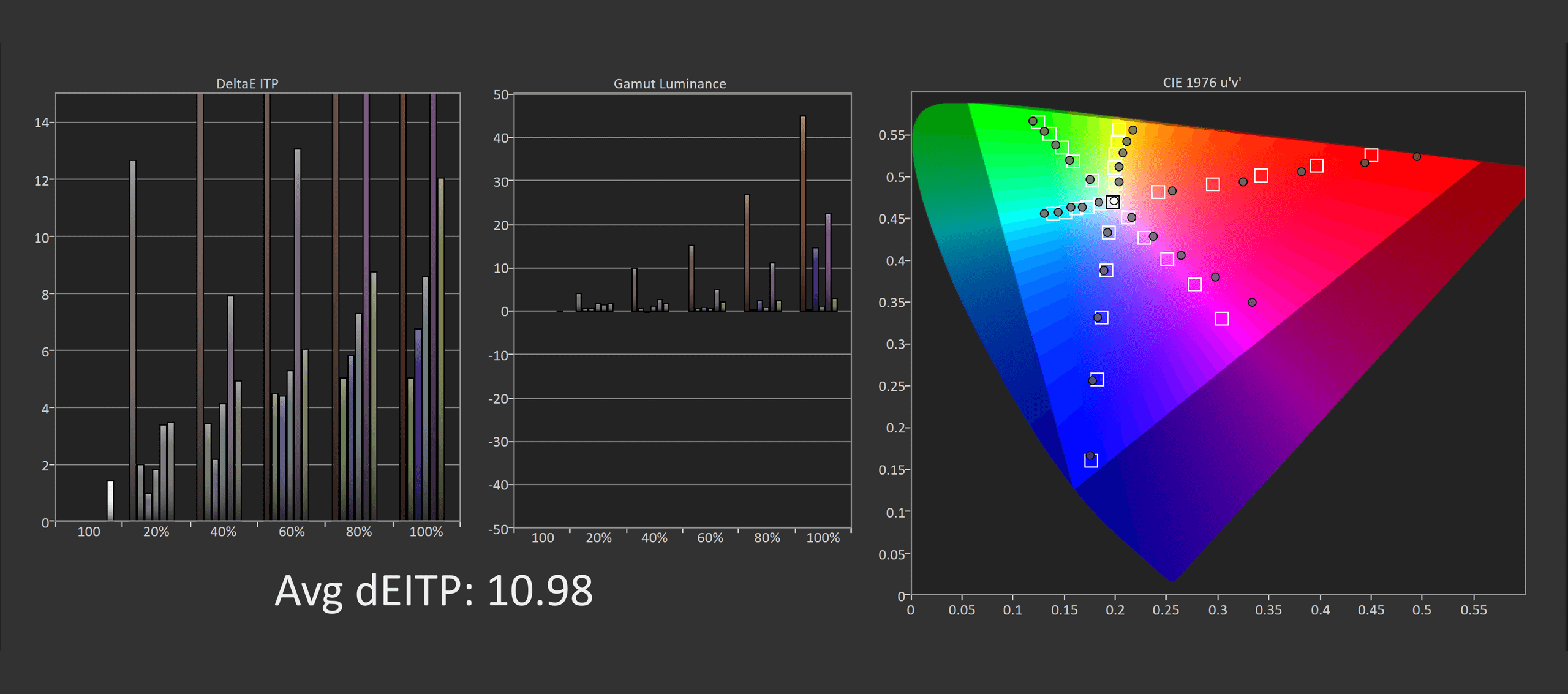

What we get from the Gaming HDR setting is definitely usable and playable though not ideal accuracy and there are few if any other settings that can be adjusted. Saturation performance in this mode is a little wonky but not a deal breaker and the full brightness capabilities of the panel are preserved whether we use an AMD or Nvidia GPU, something that was problematic with some previous QD-OLED monitors I tested.

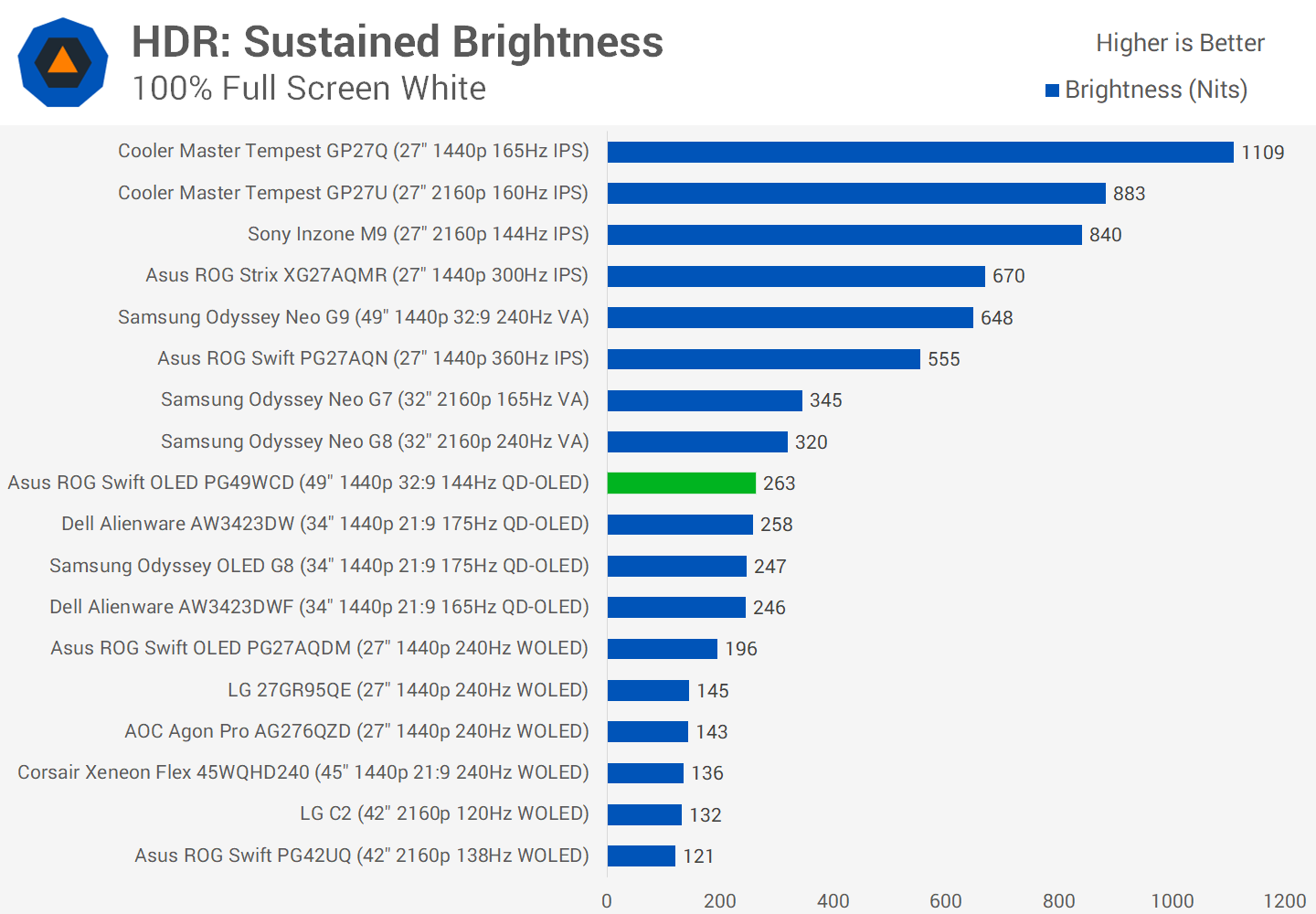

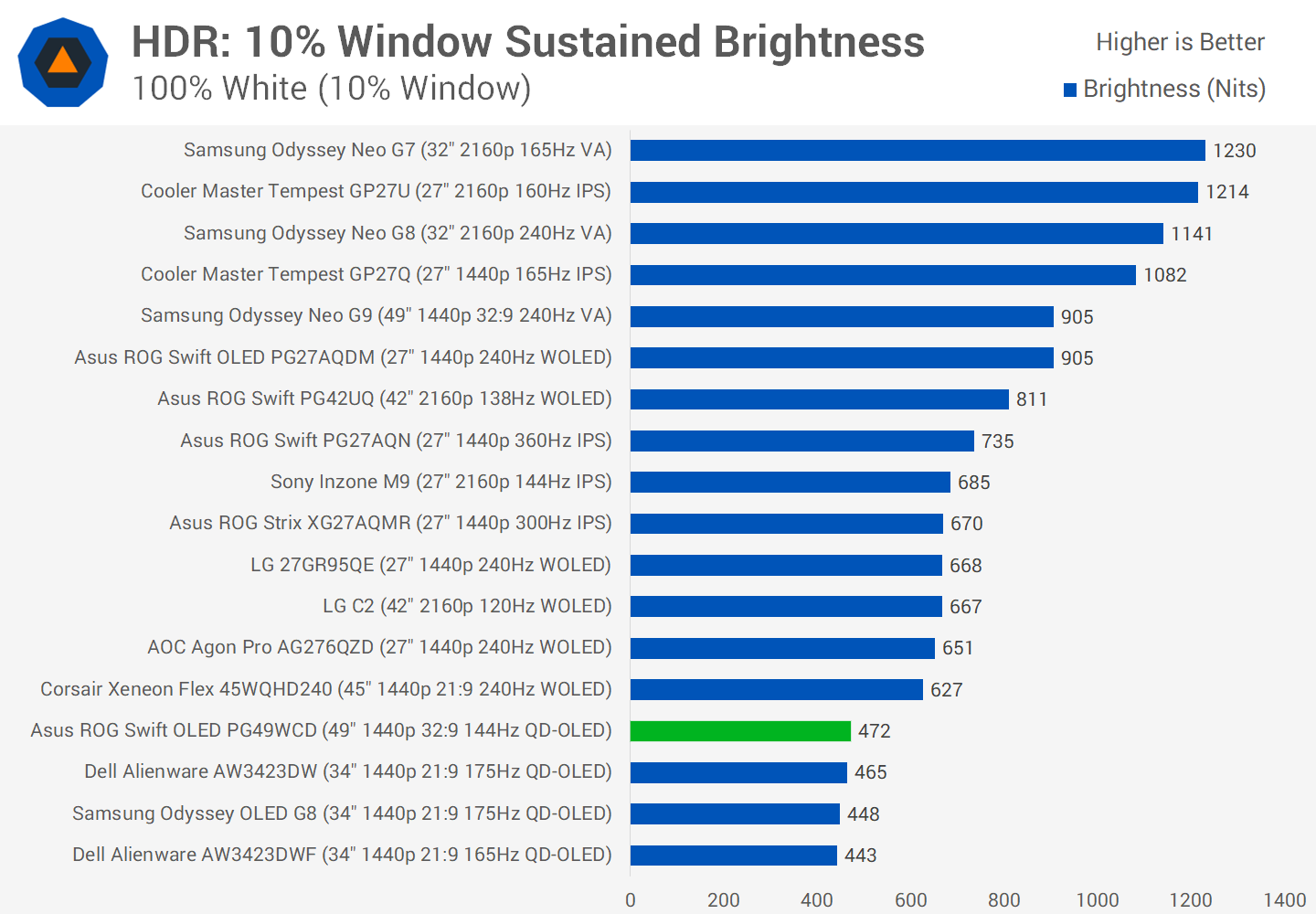

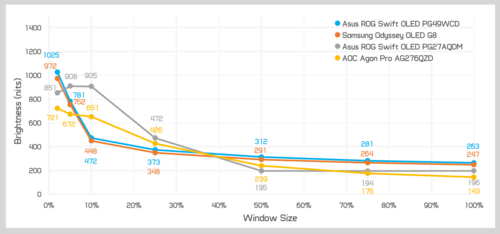

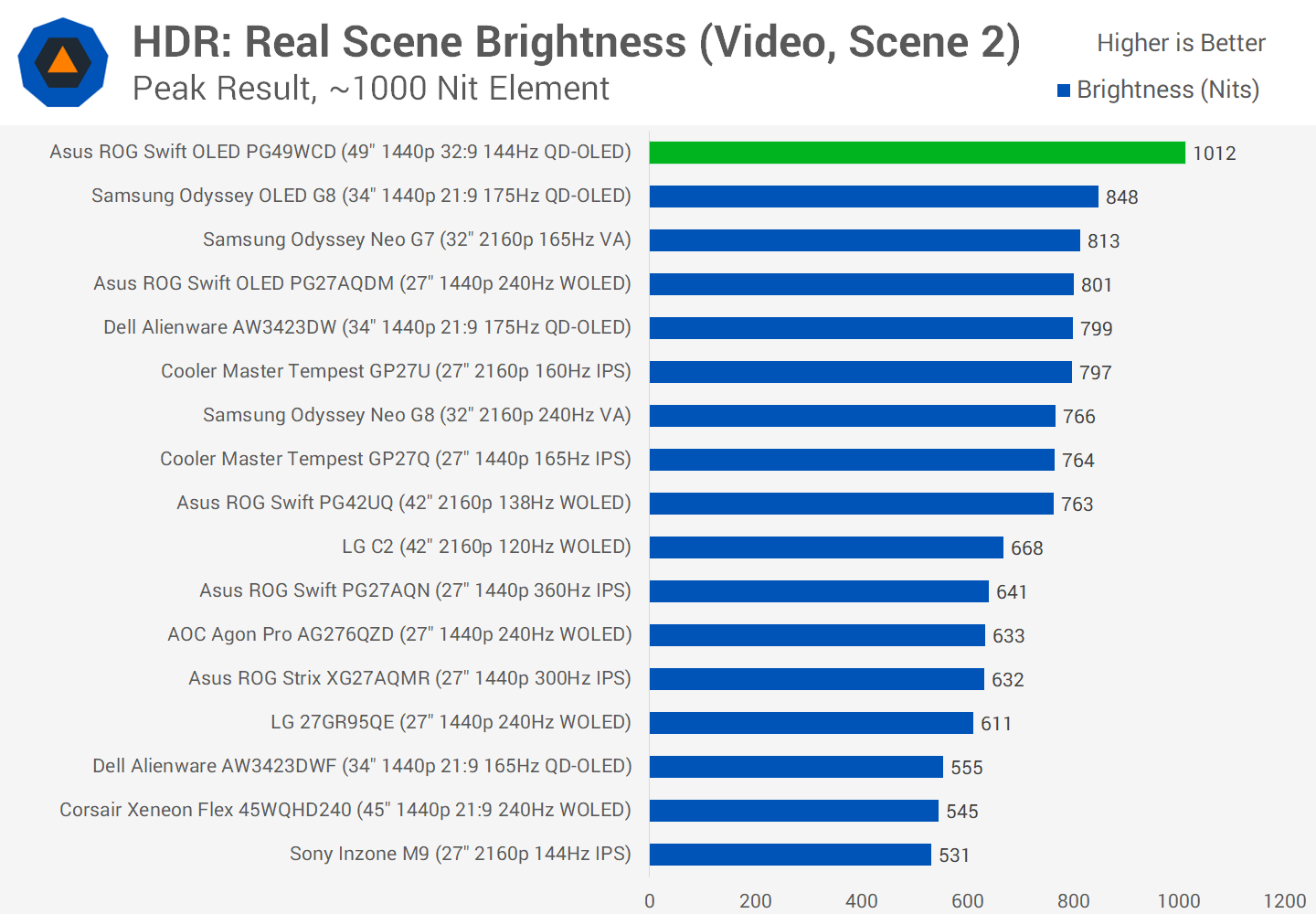

Where we end up with brightness is reasonable. Full screen brightness hit 263 nits so pretty similar to the SDR mode and not reduced for HDR content, though short of what most LCDs are capable of. 10% window brightness is similar to other QD-OLED monitors at 472 nits but not as strong as most other HDR displays such as LCDs or WOLEDs, which are brighter in this range. When viewing the smallest highlights as shown by 2% peak brightness, the PG49WCD is very strong though again not all that different to other QD-OLEDs, however it does confirm Asus marketing of 1000 nits is accurate.

HDR: Brightness vs. Window Size

Here’s what we get with brightness vs window size for a selection of OLED monitors. This second-gen QD-OLED panel follows similar behaviour to the first-gen QD-OLED used in the Odyssey OLED G8, though with slightly higher brightness at all stages. In typical QD-OLED fashion this panel type has a quick increase in brightness for small highlights, comparatively weak 10% performance, before finishing off with higher large window size brightness than WOLED panels.

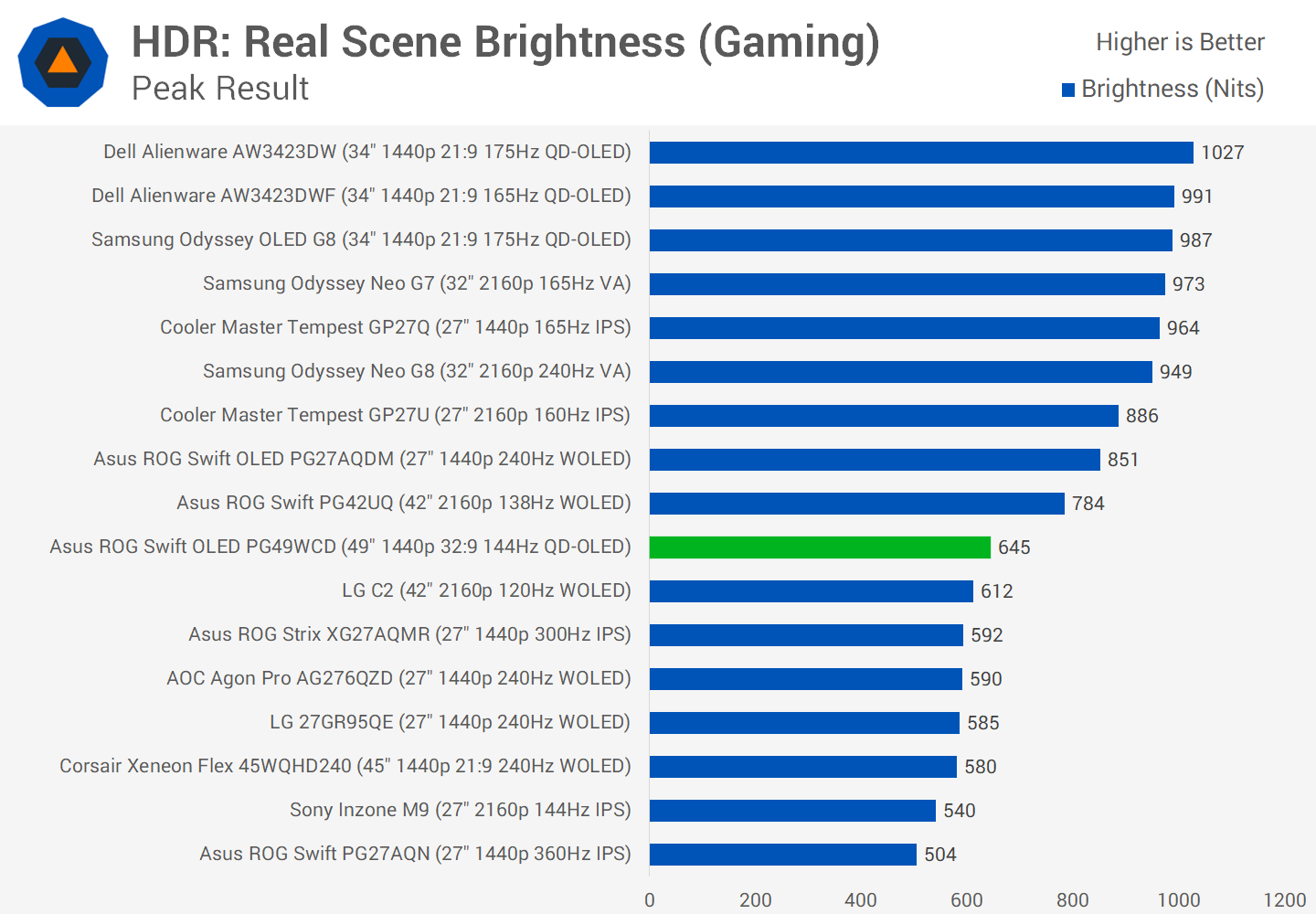

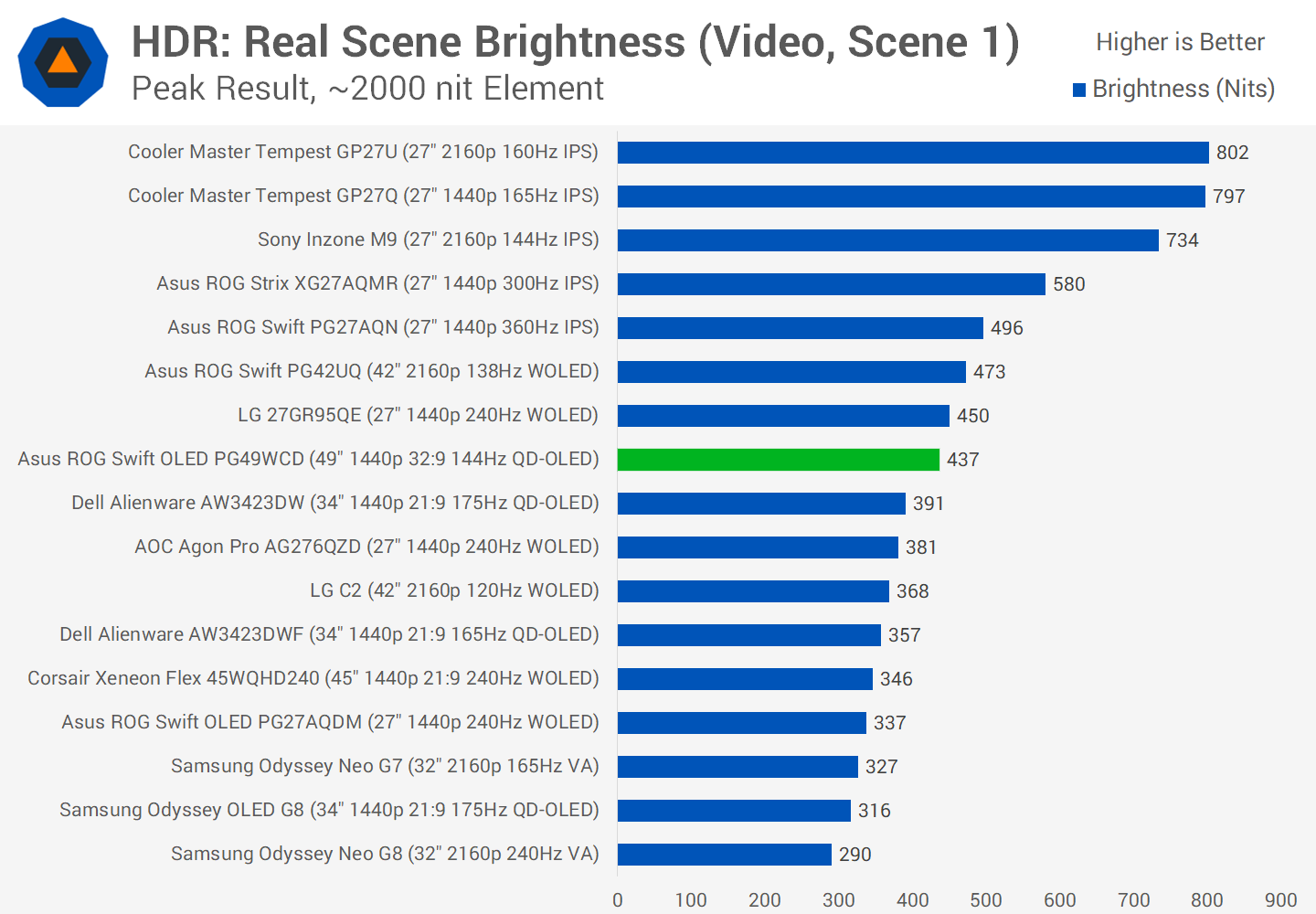

Real world brightness is pretty much as expected across the various tests. Gaming brightness was a little lower than expected, but I think this was just because the monitor is so wide that it’s showing more on screen in my test area than usual, which impacts APL and therefore brightness as well. Still I didn’t often see 1000 nits of brightness during my gaming sessions using the Gaming HDR mode, and while the Console HDR mode was brighter, it had the aforementioned highlight clipping issue.

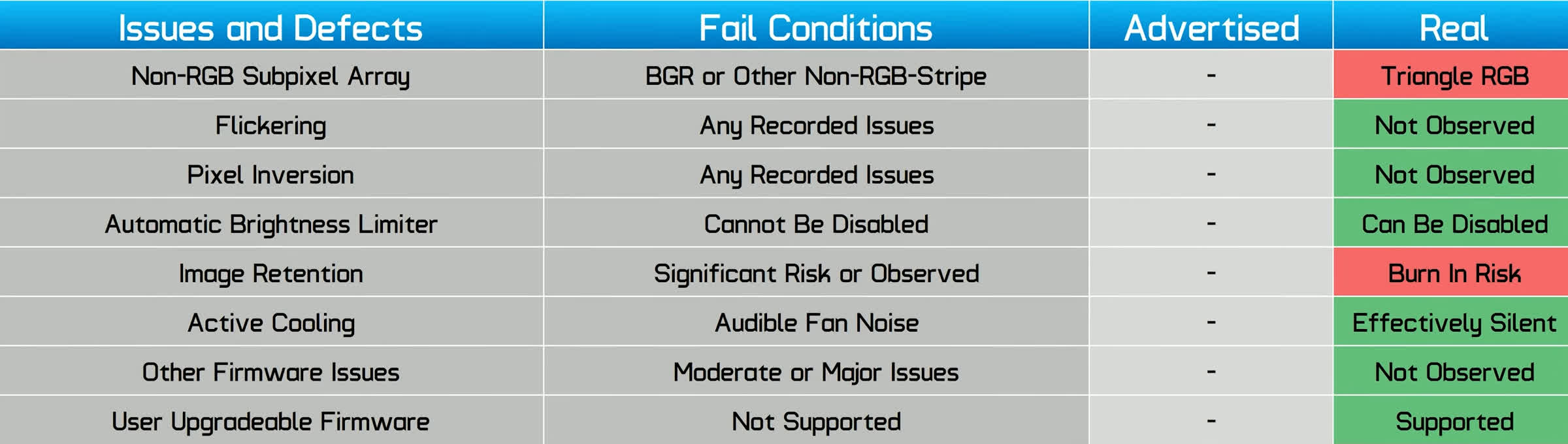

HUB Essentials Checklist

Asus does a great job of accurately advertising this monitor for the most part, delivering true capabilities like HDMI 2.1, 250 nits of SDR brightness and factory calibration. I’m not a huge fan of the 0.03ms response time advertising as I feel that’s a bit misleading, though OLEDs are still quite fast, and so far no OLED gaming monitor supports full black frame insertion technology.

But the PG49WCD is clearly a true HDR monitor and there’s only a few other issues, like its triangle RGB subpixel layout (though somewhat improved) and its risk of permanent burn in.

Ultracool or Not?

There is a lot to like about the Asus ROG Swift OLED PG49WCD – that full name is quite a mouthful – but this is another great QD-OLED offering. We do believe that due to its massive size and unique aspect ratio, it will end up as a more niche offering than the 34-inch QD-OLEDs we’ve had up until this point, however if you are interested in a genuinely very immersive gaming experience, there’s a lot this gaming monitor can do well.

The overall performance isn’t too different from other QD-OLEDs we’ve tested. Yes, Asus is using a second-generation panel, but performance is mostly the same as before. The good news is, this level of performance is quite strong: motion performance is great with lightning-fast response times, while color performance is excellent thanks to a very wide color gamut, elite viewing angles, and deep zero level blacks.

The primary audience for a product like this is someone that wants an immersive monitor for HDR single player gaming and we think Asus delivers here. The HDR capabilities of these QD-OLED panels is excellent, with per pixel local dimming, and brightness capabilities up to the 1000 nit range. Now there’s just even more width, and the resolution requirements aren’t ridiculous with a total pixel count similar to 4K.

The second-gen QD-OLED panel has slightly improved text clarity thanks to an adjusted subpixel structure, although other typical issues remain. The panel still reflects ambient light in some situations, reducing the apparent black depth. There’s also the ever present risk of permanent burn in if you use a monitor like this for desktop work, which does hamper the usability of the form factor somewhat: 49-inch 5120 x 1440 is equivalent to two 27-inch 1440p monitors side by side which would be a nice configuration for side-by-side app usage, but at the moment we can only recommend that as an occasional secondary use case. But as a content consumption and gaming monitor, the PG49WCD does deliver a great experience.

While a strong product in general, there are some areas that could do with some tidying up, like its HDR accuracy and weirdness with EOTF tracking across the various modes. I’d also like Asus to offer a proper burn in warranty with clear language posted on their website.

But there is one aspect that I just can’t get my head around and that’s the refresh rate maxing out at 144Hz. We know this panel can do 240Hz, because the Samsung Odyssey OLED G9 hits 240Hz, and other variants have been announced that also top out at this rate. We’re not sure why you would offer a reduced refresh rate when everything else seems very much top of its class? All the features are there, except that refresh rate you get on competitors, and the difference is significant enough to be noticed in both motion clarity and responsiveness.

With this major handicap, Asus simply cannot sell the PG49WCD at the same price as any of the 240Hz variants – in fact we think it needs to be significantly cheaper, which begs the question of why this isn’t a 240Hz monitor?

At launch Asus told us this display will have a $1,300 MSRP, which at first glance seems okay. The Samsung OLED G9 launched at $2,200 and then received a price cut to $1,800, which would make the Asus model $500 cheaper. Considering that many buyers going after premium gear will pay any reasonable amount extra to get the best of the best, offering the 144Hz Asus model at a $500 discount feels about right.

But, that’s only an MSRP vs. MSRP comparison. Samsung frequently discounts their monitors, especially those that have been available for a few months, so right now the OLED G9 is available for as little as $1,400. That shrinks that margin to the point where the Asus offering is just $100 cheaper, which simply isn’t enough of a discount, so hopefully Asus is prepared to follow suit and drop pricing to a more appropriate level.

And that’s basically where our recommendation lies at the moment. We’re hoping to test the Samsung OLED G9 soon to see how it stacks up, but for now we think the Asus model needs to come in at a considerable discount for it to make sense as a high-end product. It’s good, but a lesser set of capabilities must mean a lesser price.