Mounds of mouldy garbage, cigarette butts, discarded needles, used tampons, vomit and rat feces litter what was once a clean, empty one-bedroom apartment in Ottawa’s ByWard Market.

The unit above looks similar, with broken windows and walls covered in bright red spray paint.

In the building next door, kitchen tiles peel up following a flood, and the smell upon entering is overwhelming.

Brian Dagenais owns the three properties on St. Patrick Street.

He never imagined this would happen when he signed up to house supported clients through the city’s housing first program.

“I stepped on a needle about a week ago and I didn’t prick myself, it was just flat. It’s rather disgusting,” he said.

“I stepped in human crap also and I think that’s what really set me off.”

The program, which began in Ottawa in 2014, works with 11 housing agencies to give people experiencing chronic homelessness a permanent place to live, with rental supplements and support from housing workers.

It’s mostly funded through another community-based program which uses the city’s federal homelessness funding.

Agencies had to apply to be accepted into the program.

Their role is to then assess clients being supported and offer support, including the appropriate referrals to mental health services.

Housing workers are also expected to monitor client progress to make sure it’s not jeopardizing the tenancy.

Dagenais said in far too many cases that support and monitoring isn’t happening.

“The relationship for all practical purposes ends as soon as the client secures housing. It’s not supposed to work that way … They still need ongoing support and I think in far too many cases that just hasn’t happened,” he said.

Dagenais bought the properties about five years ago with dreams of one day demolishing them to build more units, but said in the meantime he had to cover the mortgage and property taxes and rented out 10 of his 13 units.

He said he was approached by several housing agencies asking if he would be willing to rent units to their clients and because of the promise of guaranteed rent and access to the city’s landlord damage fund, he agreed.

“When the agencies came to me and said the rents are guaranteed, that was a big selling point,” Dagenais said.

At the peak of tenancy he said eight of the 10 units he was renting were occupied by supported tenants.

It’s a decision he now deeply regrets.

$200K damage over 4 years

Dagenais estimates the damage incurred by supported tenants and their guests could be $200,000 over the most recent four years.

That’s partly because the units that were once all occupied are now in such bad shape he can’t rent them out anymore.

Three supported tenants remain in one of the buildings and Dagenais said the damage keep coming.

“I don’t think there is anything the city or agencies could do to make me trust them again,” he said, adding he’s also concerned that by going public the city could deny any future requests for demolition.

Dagenais said he’s worked with several housing agencies over the years including the Wabano Centre, Operation Come Home and the Youth Services Bureau.

The Wabano Centre and Operation Come Home declined a request for an interview and provided written statements instead. The Youth Services Bureau didn’t respond by deadline.

In a written statement, Wabano’s housing director Tina Slauenwhite said they had to consider client privacy but that the centre “provides holistic healthcare services to all eligible community members with due respect to their consent and willingness to receive available services.”

The statement also explained how their housing first program helps connect eligible Indigenous people with available rental units and provides rental supplements when possible.

“Following this, the relationship is primarily between the landlord and tenant, and all communication regarding concerns regarding the rental agreement is recommended to be directed through the proper channels and platforms put in place by the province,” Slauenwhite added.

Different expectations

Dagenais said that is not what at least one housing worker at Wabano promised him.

CBC obtained a copy of a response to one of Dagenais’s online rental ads in which a housing worker from Wabano wrote “we support our clients with weekly visits at first that decrease as the need for support is lessened.”

“If the big agency doesn’t have those resources, throwing it onto the landlord or throwing it onto the client or expecting the neighbours to just suck it up and deal with it [is] not really an answer,” Dagenais said.

One neighbour, who didn’t want to be identified out of fear for her safety, said she has witnessed people in desperate need of help.

“I’ve seen people beating each other with baseball bats and fights. I’ve seen people trying to throw each other off second-floor balconies. I’ve seen people overdosing in the backyard while they crawl through the trash that it’s filled with over there. I’ve seen people crawl through the trash to give them naloxone,” she said.

John Heckbert, the executive director of Operation Come Home, also cited client privacy when declining an interview. A written statement explained how the agency has “candid, constructive conversations with willing partners” about the barriers facing clients.

“We work with partners and clients to address any concerns that may arise, and we are working actively to provide more adequate and supportive options to the youth we serve,” Heckbert added.

Dagenais said since 2021 he was able to access about $71,000 from the city’s landlord damage fund to cover costs of some cleanup, however, he said he hasn’t seen any money in months.

“I believe the agencies and the city knew that a bad outcome was likely and put its selfish interests before mine and frankly before their clients, because not supporting clients who absolutely need support is a recipe for disaster,” Dagenais said.

‘We don’t want to throw bad money after bad money’

Kale Brown, the manager of homelessness programs and shelters with the City of Ottawa, said he couldn’t speak to specific cases but that the landlord damage fund was put in place in 2018 as a safeguard for landlords involved in the housing first program.

He said it can be used as an incentive to join the program and was meant to cover costs of significant damage caused by clients or their guests.

Brown, however, stressed the fund is discretionary and there are limits.

“These are taxpayers’ dollars, we don’t want to endlessly pay to fix units. That’s not the intent of the program. When we’re not able to work with those agencies to stabilize tenancies in the long-term, we do support the landlord if they want to move toward eviction,” Brown said, adding that the fund can also be used to restore units back to their original condition once an eviction occurs.

He acknowledged that during the lengthy process to evict tenants, the unit would likely get much worse.

“But the thing is, we don’t want to throw bad money after bad money,” he added.

Since 2018 the total amount of money paid to landlords through the damage fund has been increasing, with over $300,000 paid out last year alone.

The city said the rise is partly because more people know about the program, but also due to added challenges brought on by a toxic drug supply and the prevalence of mental health problems.

“During the pandemic, an eviction moratorium and limitations on an agency’s ability to support clients in their home also contributed to rising costs for damage claims,” Brown said.

The damage fund does not include rental arrears, which social assistance recipients and eligible low-income residents can apply for if their accommodation is deemed to be suitable and sustainable.

“Following that process, a decision may be made to support a payment of arrears. Payments may be issued to the client, resident or to the landlord on their behalf,” Brown said.

A landlord’s loss

In Ottawa’s Vanier neighbourhood, another landlord said he hasn’t had any luck accessing the damage fund.

Arjun Gupta purchased a multi-unit property on Cyr Avenue in 2022 as an investment.

At the time he said he wasn’t told the tenants in the four units were supported clients, helped into housing by the Ottawa branch of the Canadian Mental Health Association (CMHA).

Like Dagenais, Gupta said the clients weren’t receiving the proper support and the property was severely damaged.

Now, it sits boarded up and Gupta said he plans to surrender the building back to his bank and take it as a loss.

“If you cannot clean it up, you cannot rent it. You cannot. Like if the city is not paying for the damages I cannot get it repaired and to avoid people moving in and causing more damage, so [I] got it boarded up,” Gupta said.

Simon Beckett, the owner of Pivot Turn Property Management, helped manage the property for Gupta for about a year and said he was “stonewalled” whenever he tried to seek damage funds from the city.

He said he submitted paperwork that was lost and was given the runaround with employees away on vacation for months.

“We submit forms, we inquire through email, and we have no response for weeks or months on end. So at the end of the day, once we did get a hold of somebody, oh, they need this, oh, they need this. And there are so many levels … move in reports, photos, checklists that we don’t have because we weren’t involved in the initial move in of these tenants,” Beckett said.

The city said it would not comment on specific cases. Beckett doesn’t blame one particular party, but said the deterioration of the building was a combination of errors by the landlord, the city and the CMHA.

“I am a supporter of housing first, but the problem here is … once they’re in, they’re left to their own devices.”

CMHA workers ‘doing what they could’

Lisa Medd, the housing team program manager at CMHA Ottawa, said the agency can’t take any responsibility for the downfall of Gupta’s property because she said housing workers were providing support where they could.

Like Wabano, she said that it is a consent-based program.

“It was a building that had been owned by one landlord, sold it to another landlord. It wasn’t in good condition when that happened. We were doing what we could in terms of support, we were actually working to try to get people out because there were property maintenance issues,” Medd said.

The CMHA said only three of their clients had lived in the building and they had either moved out or been removed from their roster, but being removed from the roster doesn’t mean the clients have to leave the house.

“They can still be a tenant there and issues may still arise … so we can provide some coaching to the landlord on how to deal with that situation,” said Mike Murphy, the housing co-ordinator for CMHA Ottawa. He said they referred the landlord to the city for help and that was the end of their involvement.

The association said between 2012 and 2022, 704 people went through its “intensive case management” program, which they said goes hand in hand with housing first.

Of those, about 66 per cent completed the program. The rest either died, were relocated or otherwise dropped out. (These numbers don’t account for people who were still enrolled at the end of 2022.)

If you remove the clients who passed away, about 25 per cent didn’t have success.

The city said it has checks in place to ensure agencies are monitoring their supported clients with a system that requires workers to record their case notes and the different touch points they have with clients.

Expectations of housing first

Tim Aubry, a University of Ottawa professor and co-chair of the Canadian Housing First Network, said there is a recognition in housing first programs of the need for enriched addictions treatment.

He said CMHA Ottawa has strong programs in place.

“It’s quite variable what people are getting in housing first programs and we certainly know that it can contribute to some of the issues … that lead to eviction,” he said.

Aubry, who was part of the seminal At Home/Chez Soi project on this care plan, also noted that housing first without support is simply not housing first. In order for the model to be successful, he said the principles of rental supplements and support must be followed.

“One of the expectations in housing first programs is that there’ll be weekly contact with people … [so] the program has a good handle on what’s going on,” Aubry said.

That’s what happens at Options Bytown, another agency working with the city to house chronically homeless individuals.

Its executive director said more than 90 per cent of people in its housing first program are still housed two years later.

“The support is really intensive. Our staff go on site into these apartments to support people so they’re able to watch for anything that might be going sideways with the tenancy and intervene early on,” Catharine Vandelinde said.

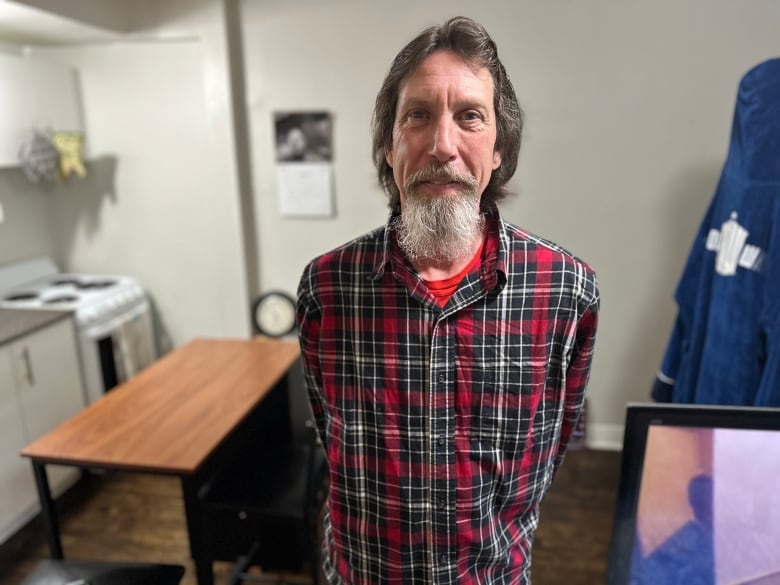

Jim Macneil is one of those success stories.

The 54-year-old just moved into his own apartment in November after couch-surfing and staying in shelters for decades.

“I’ll be 55 soon, I’ve been struggling with addictions for the past 40 years,” Macneil said, adding that without the support from his housing workers, he wouldn’t be where he is.

“I’ve never really had my own place I can say is my place … It’s hard being alright being alone, but it’s getting better. The Options Bytown people are always there for me,” he added.

Back in the ByWard Market, Dagenais said his tenants didn’t receive that type of wraparound support and now he’s left cleaning up the mess.

“My suffering is nothing like these clients and some of their guests, but I just shake my head. It’s quite sad and that’s where I get quite disappointed.”

“I do think that better efforts really need to be employed by some of these agencies and also the city.”