The creation of social housing and the maintenance of existing units have been hobbled by underfunding

Article content

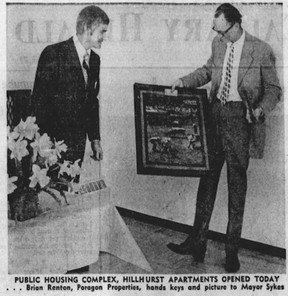

On a warmer day in February 1974, as a cluster of clouds gave way to a patch of azure, Calgary’s then mayor, Rod Sykes, unveiled the city’s newest housing project in the northwest community of Hillhurst.

The 10-storey Hillhurst Apartments gave residents a panoramic view of the city’s skyline and a place to stay in exchange for rent linked to their income.

Even as Sykes displayed a sense of pride during the opening of the building, he defended the project against opponents of public housing. He pushed against a council member who wanted the city to stop supporting such “projects for the poor.”

Advertisement 2

Article content

Instead, Sykes announced the complex would alleviate the social stresses of those with lower incomes.

Fifty years later, the building stands as an artifact in a neighbourhood that has since seen several transformations.

The property, flanked by a Mediterranean restaurant and several newer apartment complexes, is coated in grey with a façade designed in haphazard dashes that look like a collection of scars. Rebar juts out of a lower balcony, leaving behind wiry cracks. Beside the entrance, a pothole is filled with water. The carpet at the entrance is invaded by dirt.

An apartment on one of the top floors bears a sign that states, “So, this ain’t home sweet home, adjust.” In it lives Diana Bliss, who moved to the flat about three years ago with her adult son who is on AISH owing to an autism spectrum disorder. Despite the building’s poor condition, she said she is grateful to the residence for saving her from homelessness.

Bliss, who is 69 and has severe arthritis, lived with her son in a basement suite two blocks from the apartment complex until 2021, when her landlord raised her rent by $700, to $1,900.

Advertisement 3

Article content

“When they said they were raising the rent that was going to push us out of that apartment,” said Bliss, who is on a fixed income through an old-age pension program.

Then, she received news her application for public housing was approved by the Calgary Housing Company (CHC) — the city’s largest housing provider — and soon she moved into Hillhurst Apartments, where she pays 30 per cent of her and her son’s income toward rent.

The walls in Bliss’s living room, which faces her balcony, are lined with artwork from loved ones and a shelf with books from religion to political science. Beside the balcony is an exhibition of plants, featuring corn, philodendrons and aloe vera. As Bliss stepped onto the platform, she pointed at the cracks on the parapet that ran along the entire structure.

When Bliss first entered the apartment more than two years ago, she was pleasantly surprised to learn she was moving into a newly renovated space. But as she settled into her new home, she spotted several defects — a knack she acquired from her late husband, who was a property manager.

Soon, she found problems with the apartment’s heating — which for a while gave off a “swampish” stench — a garage that was accessible to non-residents, garbage bins that overflowed with litter and an amenity room she was told had been locked for over five years.

Article content

Advertisement 4

Article content

Her neighbour, Kavin Sheikheldin, moved into the apartment complex with her mother around the same time as Bliss — although her relationship with the CHC began when she was born.

Sheikheldin, who is 25, relocated to Hillhurst Apartments after her previous residence in Bridgeland Place — also managed by the CHC — was shuttered due to several problems, including flooding, infestations and outstanding repairs that were too costly and significant to have residents continue living while the building was being redeveloped.

Even as Sheikheldin finds her new residence in better shape than her previous home, she encounters problems.

“There’s no visitor parking; I sometimes notice drunk people sleeping inside the building; and when I call CHC, they don’t respond fast enough,” Sheikheldin said.

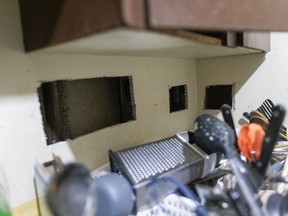

Some residents have it worse. In an apartment viewed by Postmedia, cabinet doors were falling off. Its walls had unpatched holes drilled by plumbers several years ago, and the kitchen sink, its resident said, got clogged every so often.

CHC wrote in an emailed statement that the organization plans to renovate the building later this year.

Advertisement 5

Article content

The apartment building in which Bliss and Sheikheldin live is one of many affordable housing properties nearing the end of their lives.

Units of a different era

Ageing assets are one of CHC’s highest risks, according to the city’s 2022 corporate asset management plan.

“A large percentage of Affordable Housing infrastructure is over 50 years old and the level of investment over the next 10 years is important for the longevity of its service life,” the report states.

Such problems don’t just extend to properties owned by the city or the CHC. More than four-fifths of Alberta’s affordable housing stock was in “fair and poor condition,” according to a 2021 annual report by the Ministry of Seniors and Housing — now the Ministry of Seniors, Community and Social Services. An asset management framework highlighted $1 billion in deferred maintenance in these units, which accounts for many fair and poor ratings.

Most of these buildings hail from a time when governments of all levels rapidly produced social housing for a growing population. Canada built between 20,000 and 30,000 such units every year in the 1960s and ’70s.

Advertisement 6

Article content

So much social housing, which was largely funded by the federal government, flooded the market with cheaper options.

As researcher Greg Suttor writes in his book, Still Renovating, the climate of opinion then was that governments could “solve” poverty, and welfare subsidies shouldn’t be reserved just for the elderly or the ill but for the broader middle and lower-middle class. However, by the 1980s, as record-high inflation and deficits haunted government coffers, a new political ideology arrived.

The federal government slashed social spending while offering subsidies for home ownership. In 1993, it went out of the business of creating affordable housing altogether, and three years later, it downloaded the responsibility onto the provinces.

New affordable housing all but stopped in Alberta between 1996 and 2004, according to research compiled by Suttor.

Since then, the creation of social housing and the maintenance of existing units have been hobbled by underfunding, said Byron Miller, who teaches urban politics at the University of Calgary.

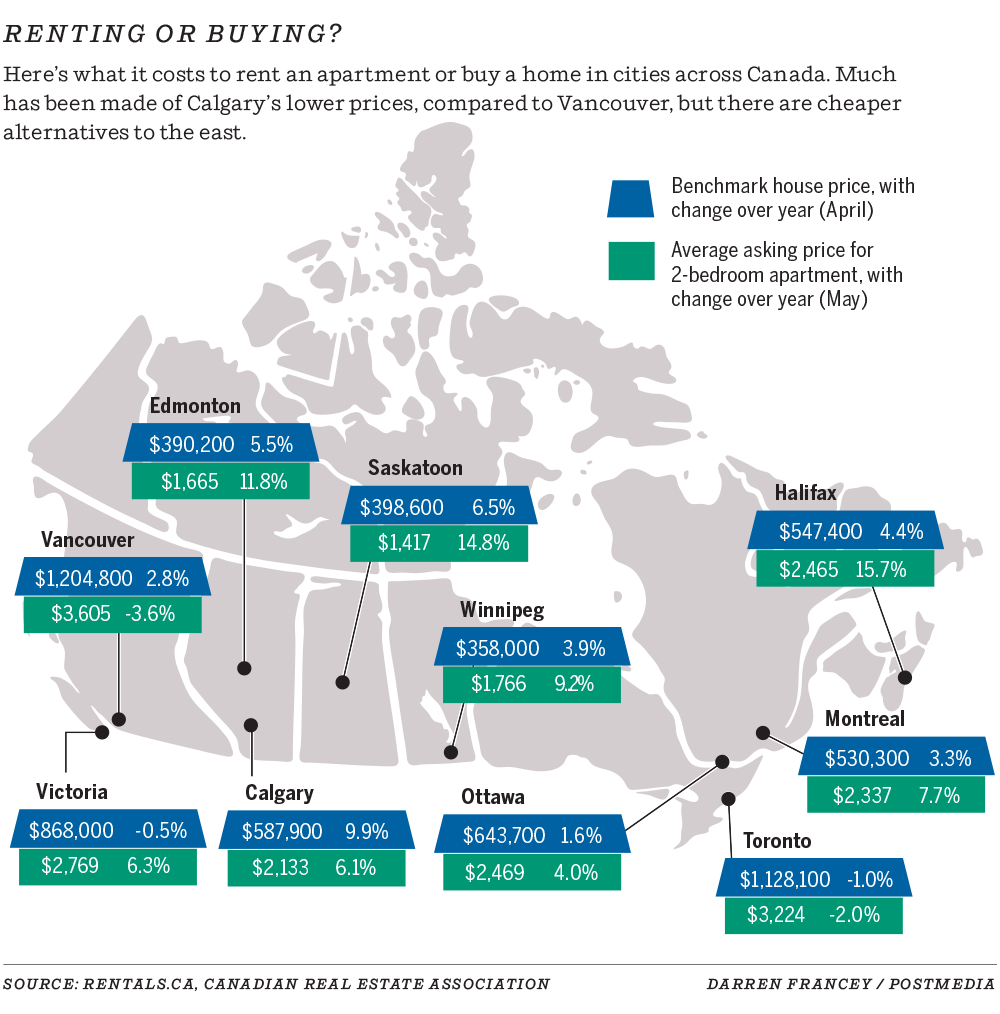

Decades later, as soaring prices are making it harder for people to buy homes and skyrocketing rents are squeezing many with low incomes out of their residences, conversations around affordable housing have attracted a renewed interest from not just advocates in the community but all levels of government.

Advertisement 7

Article content

Who funds social housing in Calgary?

Even after the massive budget cuts in the 1990s, affordable housing has been a responsibility shared among the federal, provincial and municipal governments — with Ottawa funding and creating cost-matching initiatives, Alberta playing the role of regulator and funder of programs and Calgary operating buildings, implementing strategies and contributing modest amounts of money.

Several efforts have been made since the 2000s to grow the network of affordable housing in the province — including a plan in 2008 by Alberta to end homelessness in 10 years. The strategy borrowed from the concept of housing first, in which those experiencing homelessness are offered permanent housing irrespective of whether they’re “ready” to maintain it.

However, the province slowly lost interest in the strategy, according to a government official interviewed in housing researcher, Nick Falvo’s, chapter in the book, Anger and Angst: Jason Kenney’s Legacy and Alberta’s Right. The plan was dropped and the office overseeing it was quietly disbanded before the 10-year mark when the NDP was elected to government.

Advertisement 8

Article content

Affordable housing has recently experienced a sort of revival with Ottawa’s National Housing Strategy, which culminated in a cost-matching agreement between the federal and provincial governments in 2019.

The federal government promised financial assistance for maintaining existing buildings, money for rent supplements and capital funding for new projects — more than $40 million of which has been invested in Calgary.

Alberta’s plan for affordable housing

Coinciding with the national strategy, in 2020, Alberta’s then-premier Jason Kenney called a panel of 10 experts to recommend how to “transform affordable housing” in the province.

The panellists made several findings: Almost half of the affordable housing units were owned by the province, and many were operated by other organizations, including non-profits and municipalities, in an environment that made it difficult to redevelop the buildings. And since the province owned most properties, housing providers couldn’t leverage them to build more projects as existing units were growing old.

Advertisement 9

Article content

If Alberta were to sell or transfer these properties, the panellists suggested the proceeds be placed in an investment fund dedicated to affordable housing. Lastly, the panellists recommend the government shift its role from the owner of affordable housing to “regulator, policy maker, planner, funder and enabler of the sector.”

The recommendations informed the province’s housing plan titled Stronger Foundations: Alberta’s 10-year strategy to expand and improve affordable housing.

Its main goal is to build 13,000 affordable housing units while providing rent supplements to 12,000 more households within the decade.

Following the panel’s recommendation, the province intends to achieve its targets by moving away from property ownership. It will either transfer its lands to operators or sell them on the open market with proceeds flowing into a fund for affordable housing. Alberta’s asset management framework suggests the sale of 20 properties every year over the decade.

“Transitioning from owner to regulator and funder will create more flexibility and financial independence for housing management bodies and other housing operators while making sure Albertans have better access to affordable housing that is well maintained and meets the need of their community,” Alexandru Cioban, press secretary for the Ministry of Seniors, Community and Social Services, said in an emailed statement.

Advertisement 10

Article content

The strategy also gave birth to an initiative called the Affordable Housing Partnership Program, which distributes capital grants to eligible organizations.

Recommended from Editorial

-

Squeezed: Navigating the high cost of living in Calgary

-

‘Hope on the horizon’: Interest rate cut welcome but unlikely to have immediate impact on affordability

-

Dream home or one-bedroom condo? What will $700,000 buy you in housing markets across Canada

-

‘Food insecurity is at a crisis point’: Advocate argues policy changes are needed

-

Why has shrinkflation run rampant and when will it end? Plus, 11 startling examples

‘A step backwards’

University of Alberta professor Joshua Evans criticized the plan, saying even though Alberta has increased its spending in the sector, in some ways, it is repeating the actions of the federal government in the 1990s when it transferred the responsibility of affordable housing to the provinces.

“The provincial governments were playing a central role,” Evans said. “They weren’t just enabling or investing in housing; they were setting up their own housing corporations and building housing. And so, what the Government of Alberta is doing with this strategy is actually taking a step backwards.”

Advertisement 11

Article content

Among other issues, he said the targets aren’t high enough to meet a growing demand.

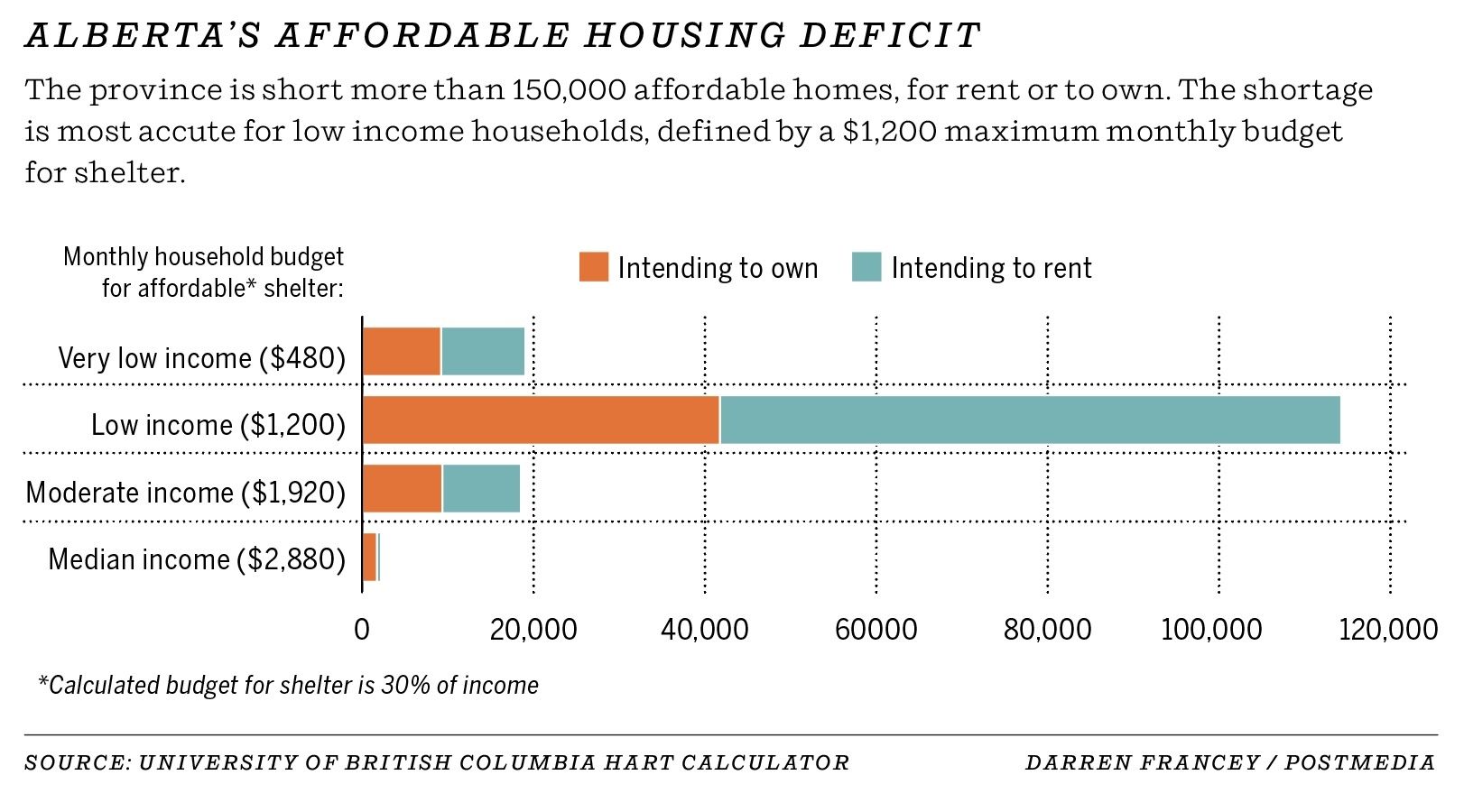

The government aims to subsidize 82,000 housing units by 2030 by building more affordable residences and providing rent supplements. However, more than 92,000 renters in Alberta live in spaces that either are in disrepair or cost more than 30 per cent of one’s income.

“The problem is that’s the need that exists today, and they want to create that stock by 2030,” Evans said. “These targets are way below what we actually need going forward.”

Evans also wonders how the government will achieve its aspirations.

In its most recent capital budget, Alberta committed $848 million over the next three years for affordable housing — close to twice the amount it promised last year and four times as the year before. However, it has only allotted $62 million this year for new projects and retrofits, nine of which were in Calgary.

“For the general public, that might sound like a lot of money,” Evans said. But for a growing province, “it’s like a drop in a bucket,” he added.

“A lot of (the funding) is going towards things like maintenance of existing buildings and programs.”

Advertisement 12

Article content

Although Alberta plans to spend $139 million on new projects the next year and $204 million the year later, Evans is skeptical. “We’ll see if those investments materialize or if it just continues to be these small amounts in the range of $60 million,” he said.

He also takes issue with the province’s intention to sell existing units.

Cioban told Postmedia that the province has sold nine assets so far — most of them single-family lots — none of which are in Calgary.

Meanwhile, Alberta has transferred 134 units to six housing providers under the condition they will continue to provide affordable housing for 20 years, although Cioban didn’t specify the recipients of the provincial assets.

He stressed the province would only sell vacant units and no current tenants would be affected by the sales.

“But after those tenants move, it would just presumably become market housing,” Evans said. “It’s foregoing the long-term benefit of holding land in the public trust for public benefit for a short-term financial gain.”

Related

Advertisement 13

Article content

Mixed-income housing

Alberta’s strategy redefines affordable housing. Previously, rents in most of the province’s units were 30 per cent of the household income. Moving forward, most rents in newer developments will range between 60 and 90 per cent of the median market rate. Advocates have argued such a policy could hurt people with very low incomes.

The government also plans to ramp up mixed-income housing developments, in which residents of various income levels, who live as neighbours, are charged different rents, allowing operators to offset the cost of subsidized units. The government outlines that most of these units will be built in partnership with organizations such as non-profits and municipalities.

On the southeastern tip of Calgary, in Bridlewood, a line of row houses painted alternatively in black and white frame the perimeters of what was once a temporary fire hall. Cutting across the buildings is a pathway that opens to a gas station and retail plaza.

The 62-unit complex is the newest project by CHC — a wholly-owned subsidiary of the city that, among other initiatives, oversees the development of new non-market housing funded by different levels of government. The project cost more than $18 million and was financed mainly by the province and city.

Advertisement 14

Article content

The units — 48 are two-bedroom apartments and 14 are four-bedroom flats — are complete with vinyl flooring, a washer and dryer, and a balcony. The complex also boasts solar panels (a 12kW solar photovoltaic) that reduce greenhouse gas emissions and the money people spend on utilities.

Five of those units are reserved for households qualified by the CHC for a rent of 30 per cent of their income. Tenants in seven apartments are charged between 50 and 70 per cent of market rents — from $700 for a two-bedroom to $1,395 for a four-bedroom. And the remaining 50 units rent for 10 per cent below what’s offered in the market between $985 for a two-bedroom and $1,975 for a four-bedroom.

To qualify for subsidized flats, those interested must apply to the CHC, which has a waitlist of over 7,000 applications. The near-market rentals, however, are available on a first-come-first-serve basis on platforms, including RentFaster.com.

CHC president Sarah Woodgate acknowledged most rents in the complex are well below 60 or 90 per cent of the market rate.

“If you looked at market rents, they are approaching double what we offer,” Woodgate said. “That’s because of what’s happened with these rent increases in recent years — we’re hearing (they’re rising by) about 20 to 30 per cent every year.”

Advertisement 15

Article content

In contrast, she said the organization doesn’t raise rents as quickly.

Why?

“We run it like a business, except there’s no profit,” she said.

The goal, Woodgate said, is to earn enough revenue to maintain the apartments without an operating subsidy from the government — which she said would solve the problem of deferred repairs that have worsened the state of public housing units.

To serve others in line, the organization hoped those paying the highest rents would eventually transition either to the private sector or homeownership.

However, many aren’t moving, said Woodgate. “We see, historically, about 100 families move into homeownership every year, and about 1,400 units open up since previous tenants mostly move into private rentals.”

That number has halved due to soaring market rents.

As a result, the organization is left with the only option of increasing supply to accommodate a growing number of people. Woodgate talked about several upcoming projects by the CHC, including a 16-unit development in Mount Pleasant, a 48-unit housing complex in Varsity and the rejuvenation of Bridgeland Place.

Advertisement 16

Article content

She said governments have shown a growing interest in affordable housing in the past few years — with Alberta’s Affordable Housing Partnership Program, Ottawa’s new fund to help non-profits acquire private units to preserve existing rental rates, and Calgary’s proposed housing strategy that among other efforts, would incentivize homeowners to build secondary suites, modestly fund affordable housing, and sell city-owned land for non-market residential units.

Woodgate also said she was grateful for the province’s 26 per cent hike in CHC’s operating budget.

However, she added the capital funding for new projects is insufficient, and the units being built by the organization and other non-profits are nowhere near the demand for affordable housing. “We can’t build new housing fast enough,” she added.

“The gap is so huge, and the market is changing every day.”

As the conversation turned glum, Woodgate mused about the past.

“I wish I could have been around when thousands of units were being opened in four years and then thousands more in another 10 years,” Woodgate said.

Advertisement 17

Article content

“I think that’s possible.”

But that depends on the priorities of Canadians.

“How people feel about government money going in to pay for capital so that people can have homes I think is important,” she said.

“And is housing going to be relied on as a commodity and as something delivered mainly by the private sector or is there interest from Canadians in having governments once again support housing as was supported post-war?”

We know the rising costs of groceries, mortgages, rents and power are important issues for so many Calgarians trying to provide for their families. In our special series Squeezed: Navigating Calgary’s high cost of living, we take a deep look into the affordability crisis in Calgary. We’ve crunched numbers, combed through reports and talked to experts to find out how inflation is impacting our city, and what is being done to bring prices back to earth. But, most importantly, we spoke to real families who shared their stories and struggles with us. We hope you will join the conversation as these stories roll out.

This week: Priced Out: The Rising Cost of Housing

Still to come:

- The Cost of Doing Business

Article content