The N.W.T. languages commissioner says the territorial government hasn’t done enough to ensure people can access services in the territory’s official Indigenous languages.

“They could do so much more,” said commissioner Brenda Gauthier. “It does not appear that the government is setting up their policies to make language within the institutions successful.”

Under its Official Languages Act, the N.W.T. recognizes 11 official languages — nine of which are Indigenous.

However, Gauthier said the wording in the act creates an inherent inequality.

“If you really review the legislation, it’s almost like it’s in different levels of language. Like you could see English and French as the higher, main languages, and then there’s nine lower-level Indigenous languages. They don’t seem to, even in the legislation, come across as all equal languages,” said Gauthier.

Specifically, she pointed to some of the wording in the act. Essentially, it says residents have a right to receive territorial services in one of the official Indigenous languages in a region or community where that language is spoken and there is “significant demand” for that language.

However, Gauthier said part of the issue is there’s no definition for “significant demand.”

She also pointed to how the territory handles translation services for French versus Indigenous languages.

Within the government’s Francophone Affairs Secretariat there are staff members dedicated to French translation services. For translation into the Indigenous languages, departments would reach out to local translators and interpreters.

Briony Grabke, a spokesperson for the department of Education, Culture and Employment, said that since July 2023, the Indigenous Languages and Education Secretariat (ILES) has been helping co-ordinate translation requests more formally within the government. The secretariat is also building a terminology database that can be used in the future.

Day-to-day effect

These gaps, said Gauthier, have a real-world effect on N.W.T. residents.

Sharon Allen is a Dene Zhatié speaker and language advocate. She’s also found herself as an unofficial interpreter for family members dealing with territorial services — especially health care.

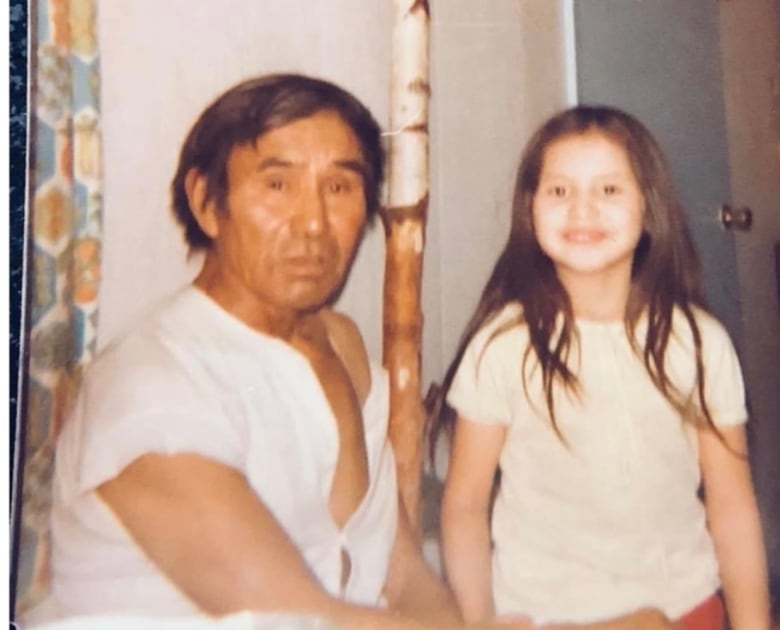

She grew up with her godparents who taught her the language. Allen was 24 and training as a nurse when her godfather Gabriel Sanguez was diagnosed with cancer. She became the go-between to try to explain his treatments.

She found herself in a similar situation more recently when on medical travel with her mother. While she said there was an Indigenous liaison to co-ordinate the travel Edmonton, there wasn’t anyone that could deliver information in the language.

Allen acknowledged that her mother understands English, but “when it comes medical travel, you really need to know the proper names for a person to get proper care.”

“She wouldn’t have had that otherwise if I had not gone with her. Access to languages when people are in care for medical travel or anything like that is really critical,” Allen said.

Having family members fill that gap comes with significant pressure, she said.

“It would be difficult for anyone because you’re talking about your loved one’s health and the impacts that it would have on them and how that would be for you. To try to stay objective in what you’re telling them, when you’re so close to someone, that creates a barrier in itself because you have your own feelings about their diagnosis or their welfare… It is a burden, but it’s also something that you would do for your loved one anyway.”

How did N.W.T. end up with 11 official languages?

The territory first introduced its Official Languages Act in 1984. That piece of legislation formally recognized the Indigenous languages spoken in the N.W.T., though French and English were then the territory’s only official languages.

Five years later, a special committee recommended the Indigenous languages be deemed official. The government amended the legislation in 1990 to do so.

Fibbie Tatti was one of the co-chairs of the special committee on Aboriginal languages. She said that at the time, a translation program at the Legislative Assembly was cut and “that was basically the only recognition of languages back then.”

The recommendation to give Indigenous languages equal status as official languages came after the committee chairs toured numerous communities across the territory, which included Nunavut at the time.

Tatti remembers borrowing a snowmobile in Gamètì, N.W.T., and going door to door, letting residents know there was a meeting that evening.

“Maybe because of our aggressiveness in terms of trying to get people to come out, people did come and so they voiced their concerns,” she said. “The work on official languages came in from the communities.”

Today, Tatti says she sometimes gets frustrated that language revitalization work “is not going fast enough.”

Still, she sees the work around official languages as a success, both in getting legal protection for the languages and in the additional work that’s happened since, like developing language curriculum and immersion programs in schools.

“I’ll never be happy with the slowness of things, but I’m happy that people now recognize how important it is to us,” she said. “And how beneficial it is to children to be able to be bilingual and give them the tools to succeed.”

Government recognizes gap

In an emailed statement, education department spokeperson Briony Grabke said offering “frontline services in the Indigenous languages is a significant challenge and one that the Government of the Northwest Territories is currently working to address.”

She added that being able to provide those services requires the government to train staff, develop resources and scripts, and build a referral system, among other work.

Availability of language speakers and interpreters is also a challenge, she said.

In 2018, the territorial government developed an Indigenous languages action plan, which set out 17 action items. According to its online tracker, 13 of those actions are complete and four are on-track.

The ones that remain incomplete pertain to improving access to frontline services. One action item includes reviewing guidelines around significant demand, which Gauthier highlighted. Others include developing a promotional campaign on the Official Languages Act, educating staff on providing services in the language, and recognizing staff who use their Indigenous language at work.

The territory also shares work it’s done in the Indigenous languages annually.

Part of the languages commissioner’s job is hearing and assessing complaints from the public.

Gauthier says situations like the one Allen found herself in when dealing with the health care system are fairly common.

“There’s very valid concerns where there’s a lack of service in Indigenous languages,” said Gauthier. “However, what I’m seeing is despite there being a valid concern, a lot of the Indigenous population will not pursue a formal complaint… And I will admit, I struggle because I do not want to take that power away from someone and say, ‘I’m just gonna take your complaint and run with it.'”

Allen said that she’s never filed a complaint.

“I think there is the option of doing that, but sometimes people end up thinking, ‘What’s the point? They don’t do anything anyway.'”

Caitlin Cleveland, the new N.W.T. minister responsible for official languages, is hoping to change that.

“I think there’s always room for the territory to grow,” she said. She pointed to health care as an example and improving the medical travel escort program to ensure residents are receiving the care they need in their preferred language.

“I definitely want to hear from people,” she added. “I want the opportunity to learn from people, and language revitalization is definitely a focus that I will maintain in my term as the minister responsible.”

Allen also wants to see changes sooner.

“If we really want reconciliation with the Indigenous peoples, we need to make sure that our culture and our language are at the forefront of the GNWT,” she said. “We need more language speakers in the offices that we work in, and more of our people need to take the time to commit to it.”

She said she also wants to see more visual representation from the government of people learning their language, “people that we recognize in our community.”