WARNING: This article contains details about violence against Indigenous women.

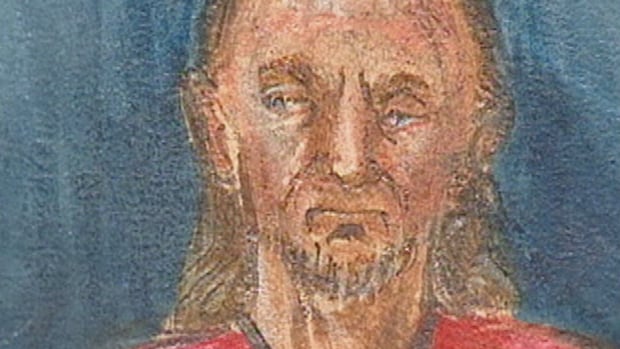

British Columbia serial killer Robert Pickton has died of injuries sustained in an attack, according Correctional Service Canada (CSC).

The 74-year-old was in hospital after being the target of what CSC called a “major assault” by a fellow inmate on May 19 at the maximum-security Port-Cartier Institution, about 480 kilometres northeast of Quebec City.

He was in a medically induced coma and on life support in the days before he died.

Pickton was convicted of six counts of second-degree murder and sentenced to life in prison in 2007, with the maximum parole ineligibility period of 25 years, after being charged with murdering 26 women in B.C.

His confirmed victims were Georgina Papin, Sereena Abotsway, Mona Wilson, Andrea Joesbury, Brenda Ann Wolfe and Marnie Frey.

The 74-year-old B.C. man was in hospital after being the target of what Correctional Service Canada called a “major assault” on May 19 at the maximum-security Port-Cartier Institution in Quebec. Robert Pickton was found guilty of murdering six women, but bragged about killing 49, many of whom were Indigenous women from Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside.

The remains or DNA of 33 women, many who were Indigenous and went missing from Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside, were found on Pickton’s Port Coquitlam, B.C., pig farm.

Pickton bragged to an undercover police officer that he killed 49 women.

After he was convicted, an inquiry was called into how police handled his case.

The Missing Women Commission of Inquiry found that botched investigations, systemic bias, leadership issues and fragmented police structures in the Metro Vancouver area all contributed to failures in catching him sooner.

One of the revelations was how warnings of a potential serial killer made by a Vancouver Police Department (VPD) geographic profiler were dismissed by VPD leadership as inaccurate and inflammatory more than four years before he was arrested in 2002.

Pickton’s name first surfaced as a suspect in the disappearances of women from the Downtown Eastside in 1997 when officers who showed up at his farm with a search warrant related to illegal firearms stumbled upon the belongings and remains of missing women.

As a result of the inquiry, provincial policing standards for missing person investigations were implemented to reflect “the important lessons of the Pickton case and other missing and murdered women investigations.”

The standards now say consideration must be given to the fact that “Aboriginal women and girls are at an increased risk of harm” and “disproportionately represented among missing and murdered women throughout Canada.”

Pickton became eligible for day parole in February, which sparked outrage from advocates, politicians and victims’ family members who criticized Canada’s justice system, saying he should never be released from prison.

The CSC release said Pickton’s next of kin had been notified of his death, along with registered victims.

“We are mindful that this offender’s case has had a devastating impact on communities in British Columbia and across the country, including Indigenous peoples, victims and their families,” it said.