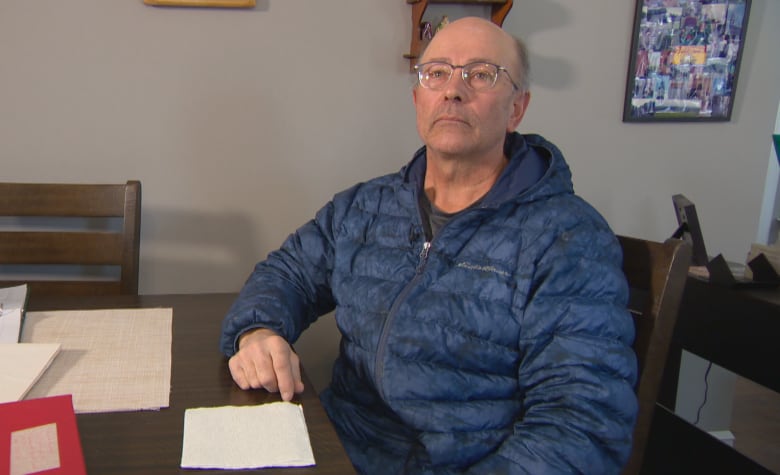

David Hunter has always been interested in science and astronomy.

In 2017, he even took a trip to Wyoming to see a total solar eclipse. Then it dawned on him: central New Brunswick will be the centreline for the next total solar eclipse.

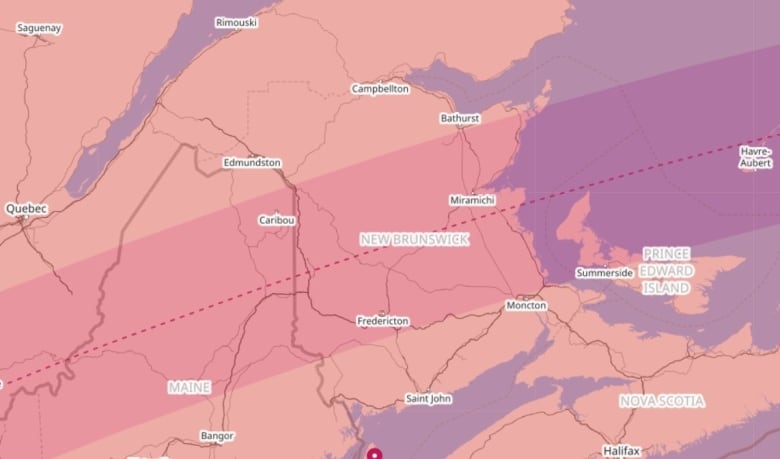

A total solar eclipse occurs when the moon completely blocks out the sun. The path of totality for the eclipse April 8 includes Fredericton, Woodstock and Miramichi, while Saint John and Moncton will experience about 98 per cent coverage of the sun.

Hunter’s hometown of Florenceville-Bristol, near the western edge of the province, is also in the path of totality, but he wanted to get closer than the front-row seat he already has.

So he hatched a plan to build what he calls a balloon-borne solar telescope.

The project is meant to get better views of the Earth, the shadow of the moon, and the sun during the eclipse from an altitude of about 30 kilometres — more than double the maximum altitude a commercial airplane can fly.

Hunter said Earth is a very special place.

“The eclipse is one demonstration of that,” he said.

David Hunter was born and raised in Florenceville-Bristol. Now he’s made this once-in-a-lifetime eclipse his hobby, building a balloon-borne solar telescope and sharing the experience with residents of Carleton North.

“We should really appreciate this and look after our home planet.”

The balloon-borne solar telescope has different parts. The 183-centimetre-tall payload is made up of multiple computers, each with a camera.

The computers have different jobs, including radio communication and taking photos to send live to the ground.

People who hope to view the eclipse from the ground should get special eclipse glasses, which are available online from reputable sellers. Experts warn of possible fakes, which could be dangerous because looking directly at an eclipse can cause permanent eye damage.

Another way to watch the show would be through a live YouTube link, which will be available closer to the eclipse, from Hunter’s team, which will broadcast the main feed.

Retirement hobby turned multi-faceted undertaking

Hunter said the project was conceived in 2019 when he moved back to Florenceville-Bristol after he retired the year before from his job in Toronto as a medical physicist.

The move brought him back to his hometown, and the place where he first saw a partial solar eclipse. That was in July 1963, and his brother helped him make a self-viewing box to watch the event.

Then in 1968, when he was in Grade 10, Hunter wanted a telescope — so he built one.

“You’ve got to have a passion about things which transcends rationality,” he said.

Hunter said it isn’t a new idea for people to send balloons up during eclipses. But he said there are two things that make this project different.

In the past, amateur balloons didn’t have a tracking telescope to get exact views of the sun.

Another unique feature of the balloon is that usually, images of the event aren’t seen until the payload has landed, which happens after the flight is terminated and a parachute carries the payload to the ground.

But Hunter’s balloon will be sending images in real time to the team on the ground.

Hunter said the cameras on the computers will be able to capture the shadow of the moon approaching New Brunswick as totality nears — something that won’t be able to be seen from the ground.

The balloon itself is a large latex weather balloon, which will be attached to the payload.

Once it launches, it can be tracked, but the wind will have control of where it goes. Hunter said he’s monitoring the weather and on the day of the eclipse, launch time can be adjusted slightly to try to ensure the balloon doesn’t drift outside the path of totality, but it will likely be around 3:23 p.m., near the time of the start of the partial eclipse.

The time of totality will be around 4:32 p.m. in Florenceville-Bristol.

When Hunter started the balloon project, he thought it would be a little retirement hobby to keep him busy, but it got much bigger than that.

In 2020, he approached the University of New Brunswick to get students involved, and before that, he got a former colleague on board.

Organized teams for launch, recovery

He kept recruiting people for different roles, including his brother, Lawson Hunter, who is helping to communicate with NAV Canada.

There will be a launch team that will send the balloon off from the launch site at the Amsterdam Inn. People can watch it happen, but there will be a security perimeter set up around the site.

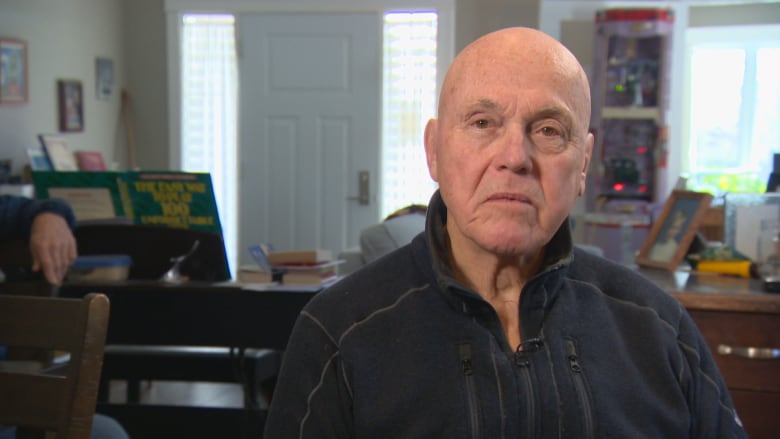

Tom Hunter is part of the balloon’s launch team. He’s also been a farmer in the area for around 40 years.

“It’s certainly a lot more exciting than some of the work that I do day to day,” he said.

“It’s a once-in-a-lifetime thing.”

He said the team has had a number of practice flights, and has also prepared for bad weather on the day of the eclipse.

There will also be a team assigned to recovering the payload once it lands — the location being an unknown at this point in the process.

Ian Giberson, who’s on the recovery team, found out about the project from a local newspaper and decided to see if there was anything he could do to contribute.

On the day of the launch, Giberson said he’ll be in a pickup truck with a radio and will be following the balloon in an attempt to rescue the payload when it lands.

“The thing goes up 100,000 feet, in theory, and … depending on the wind direction and velocity, lands somewhere, maybe in a river, maybe in the Gulf of St. Lawrence, maybe somebody’s backyard,” said Giberson.

But until that day, he said, it’s hard to tell where it will go. Usually, in practice runs, the balloon goes west to east, but during one practice round, it went the other direction and landed in Maine.

David Hunter said New Brunswickers are lucky to be able to experience a total solar eclipse, noting that the last one in the central part of the province was more than 1,000 years ago.

He called the total solar eclipse a cosmological historical event.

“Just statistically, every 400 years, any particular spot on Earth will experience a total solar eclipse, so this is a rare event,” he said.