A half-hour into his appearance before the public inquiry into foreign interference, Justin Trudeau arrived at a dramatic moment, from 2019, that would reverberate three and a half years later when Canadian journalists began reporting on a series of intelligence leaks.

In the midst of the 2019 election, security officials briefed a Liberal party official about “concerns” related to the Liberal nomination contest in the Toronto riding of Don Valley North. Those concerns were passed on to Jeremy Broadhurst, the party’s campaign director, who then ventured to the government terminal at the Ottawa airport on a Sunday in late September to meet with Trudeau, who was returning after a week of campaign travel, Trudeau recounted on Wednesday.

The prime minister and Broadhurst spoke there for 20 or 30 minutes. Broadhurst explained that intelligence officials had concerns that Chinese officials had potentially been planning to interfere in the nomination contest, specifically by transporting either students or Chinese-Canadians via bus to the polling station to vote for Han Dong, who had won the nomination. He later became the Liberal MP for Don Valley North.

In Trudeau’s telling on Wednesday, it wasn’t clear whether this plan had actually been carried out. The Liberal party’s internal process had raised no red flags about the vote. And the mere presence of buses at a nomination contest was not, in Trudeau’s view, evidence of something questionable (apparently it’s rather common).

Though it was reported in February 2023 that CSIS officials “urged” the Liberals to revoke Dong’s nomination, both Trudeau and Broadhurst have now told the commission — under oath — that no recommendation of any kind was made. Trudeau also testified that what he and Broadhurst heard was to remain secret.

So what to do?

Trudeau and Broadhurst both concluded there were not sufficient grounds to overturn Dong’s nomination.

“Overturning a democratic event, like an official party nomination … must have a fairly high threshold,” Trudeau told the inquiry. “In this case, I didn’t feel that there was sufficient, or sufficiently credible, information that would justify this very significant step.”

No doubt there will be those who second-guess Trudeau’s decision — or who believe something more should have been done to get to the bottom of what may or may not have happened in Don Valley North.

But that half-hour at the Ottawa airport seems to crystallize something important about both the problem of foreign interference and the political drama that has played out since. And it is perhaps a shame that Trudeau’s testimony only came on Wednesday.

Incomplete and closely held

The biggest problem at hand remains the undisputed (and now widely known) fact that hostile foreign states are trying to covertly meddle in Canada’s democratic process. It might be debated exactly how much of a problem it is, but the threat — both real and perceived — is now apparent.

But it is incomplete and closely guarded information that is central to many of the issues, disputes and headlines that have recently defined the debate around foreign interference.

It has been said repeatedly that what is commonly referred to as “intelligence” is not “evidence.” But it might be more accurate to say that intelligence is not always proven fact.

In the case of Don Valley North, that seemingly put Trudeau in the position of having to decide whether to dismiss a candidate on the basis of uncorroborated suspicion. Perhaps he should have. But it might at least be agreed that the decision isn’t a slam dunk.

In February 2023, questions about Dong and his nomination exploded into public view via leaks from unnamed security officials. But it would be another 14 months before Trudeau and Broadhurst explained what they knew.

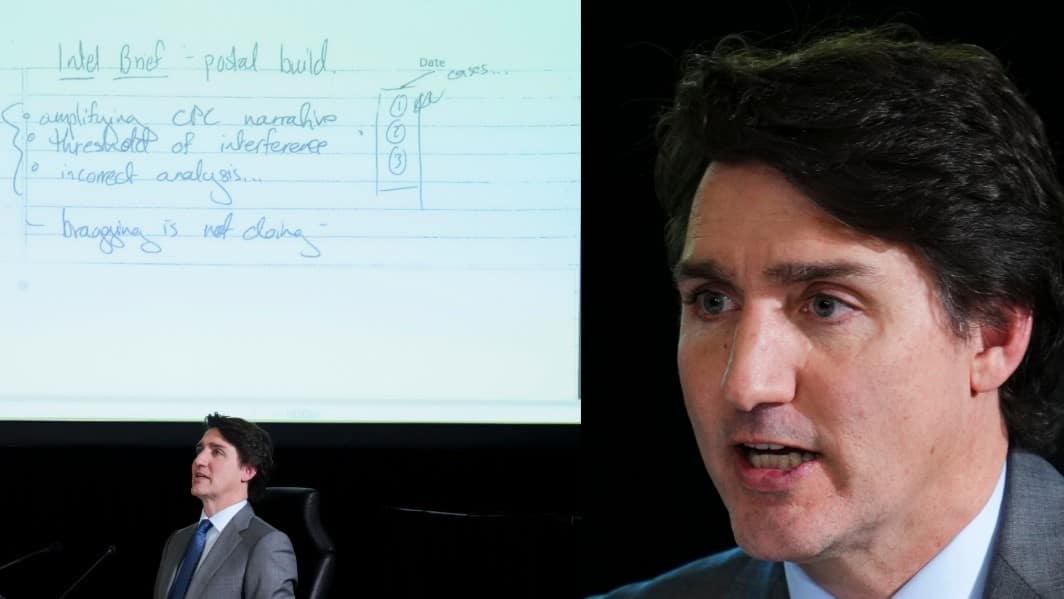

In the 2021 election, the Conservatives were concerned that misinformation was circulating on social media about the party and its positions regarding China. Erin O’Toole, leader of the Conservatives at the time, has said the public servants charged with monitoring foreign interference should have issued a public warning about the misinformation. But those officials told the inquiry they did not have enough information to conclude that the messages on social media were being co-ordinated or driven by a foreign state.

At the very least, this spring’s hearings have belatedly brought some clarity to those considerations — and further illuminated how difficult it can be to navigate a world where so much is unproven.

These hearings would certainly not be happening if not for the media leaks of 2022 and 2023 that promoted a number of significant claims. Some of those claims have now been directly disputed or qualified.

Testifying at the foreign interference inquiry, Prime Minister Justin Trudeau said it’s critical for Canadians to have confidence in their democratic institutions and maintained that intelligence shows the 2019 and 2021 elections were not compromised.

But the government has repeatedly insisted that national security kept it from responding more fully to the leaks and much was left unaddressed for months. An adviser to the prime minister testified this week that, in response to one media report, he asked whether some of the information in the government’s position could be declassified and released. Apparently he was told that wasn’t possible.

Beyond what the public gets to know, there remain questions about how well information flows within government and between security officials and political parties. At least some of the more sensational claims reported in the media seem not to have reached the prime minister until after the leaks.

Some of the confusion and intrigue of the past year and a half could be put down to the relative novelty of the problem — what we now know as “foreign interference.” For however long nations have been trying to meddle in each other’s elections, it wasn’t until the United States presidential election in 2016 that democratic nations were fully confronted to the extent of the threat posed by non-democratic regimes.

Trudeau was at pains on Wednesday to review everything his government had done to prepare for that problem and how it set up independent bodies that could deal with interference during elections and established protocols and processes. This inquiry may be demonstrating that even with all that process there will still be difficult calls to be made — and parties who second-guess those calls.

But if the past year and a half was a stress test for the Canadian political system, it can’t be said that it passed with flying colours.

Indeed, the most important conclusion might be that doubt and suspicion about the democratic process thrive in the absence of clarity and information. And while the government might not want to call a public inquiry every time someone leaks something to a reporter, greater and faster transparency and openness might be a significant part of the answer to foreign interference.