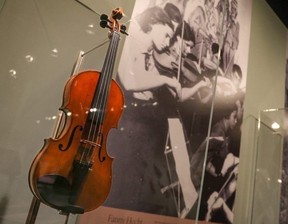

Violins of Hope loans restored instruments to orchestras for concerts and to exhibits and educational programs commemorating the Holocaust.

Reviews and recommendations are unbiased and products are independently selected. Postmedia may earn an affiliate commission from purchases made through links on this page.

Article content

In 1936, a Jewish musician brought his violin to a German luthier for repair.

Both their names have been lost to history. But the repairman secretly defiled the instrument by drawing a swastika and the words “Heil Hitler 1936” on the inside, where it remained undetected for decades. The Jewish violinist presumably played the instrument for the rest of his life, never knowing what was inside. The violin changed hands over the decades until finally making its way to America. In need of repair again, it was opened up and the hateful message was discovered for the first time. Rather than have it destroyed, or the vandalism removed, the unknown owner donated it to The Violins of Hope, a collection currently exhibited at the National Music Centre (NMC).

Advertisement 2

Article content

Article content

“It was donated to the collection under the condition that it never be repaired or played again,” said Brandon Hearty, manager of exhibition development at NMC. “It’s definitely a bit of a different piece, not just visually but because it’s a testament to the dehumanization that happened during the Holocaust and how petty and angry and bitter the people of Germany were against the Jews.”

The “Vandalized Violin” is one of 44 instruments on display as part of the travelling exhibit, which originated in Tel Aviv, Israel. The collection belongs to Avshi Weinstein, whose grandfather Moshe immigrated to what was known as Mandatory Palestine in 1938 and began working with the Palestine Symphony Orchestra. Musicians in the orchestra, many of whom had been saved from the Nazis by joining the group after founder Bronislaw Huberman secured visas for them and their families, wanted nothing to do with their German-made violins, so Moshe began buying them. The collection grew and, eventually, Moshe’s son, Amnon, became their caretaker. He gathered information about their owners and the horrors they endured. He founded Violins of Hope, an organization that loans the restored instruments to orchestras for concerts and to exhibits and educational programs commemorating the Holocaust. He died on March 4 and Avshi continues his father’s work, which included delivering the instruments to the National Music Centre, where they will be on display until June 16.

Article content

Advertisement 3

Article content

All of the instruments have a story behind them. Donated by survivors or their descendants, many of them came from ghettos or concentration camps during the Holocaust. Staff at the National Music Centre spent more than a year researching and adding to those stories.

“There is a person attached to each one of these violins,” said Hearty. “Ultimately, what this exhibition is about more than instruments is real people. It’s about trying to memorialize the tragedy that they went through, for both the survivors and victims. Because we have violins belonging to people who were able to make it; lovely, beautiful stories like the Palestine Orchestra where so many people were saved by their dedication to music. But, obviously, the flip side of the coin is also true where many, many people weren’t afforded that luxury of being able to make it through the war.”

Many of the instruments have haunting backstories. One exhibit, called The Lost Polish Boy, features a violin once owned by a Jewish boy orphaned during the Holocaust and sheltered by a family in Belgium. He would play the violin in the streets of his new home to lift the spirits of the village. One day he vanished, believed to be arrested by the Nazis. The violin he left behind was eventually given to the niece of the boy’s host family, who stored it in its case with flowers for decades before giving it to Amnon Weinstein. He restored it in Israel and incorporated the dried flowers into the body of the instrument.

Advertisement 4

Article content

Another violin features a delicate carving depicting a ghetto or concentration camp with the dates June 26, 1940, and May 9, 1945, and the inscription “Souvenir de captive,” relating to the occupation of France by the Nazis. It was believed to have been created by an unknown prisoner of war.

Some of the collection will be used in concerts in the city. The Calgary Philharmonic Orchestra will use restored instruments from the collection during its Violins of Hope concert at the Jack Singer Concert Hall on May 15. Klezmer and hip-hop artist SoCalled will perform with a string quartet, who will use the instruments for a May 26 concert at the National Music Centre. Juno-winning singer and composer Lenka Lichtenberg will also use the instruments for a June 2 concert at the NMC.

“This is a great example of how a story about music (having) many different perspectives: resistance, healing, hope, resilience, survival,” said Andrew Mosker, president and CEO of the NMC. “That’s a very common thread in music in general. We all have connections to music as a form of healing, and how we find wellness from it. This is a community of stories coming together in this exhibition.”

Advertisement 5

Article content

On Friday, the media was given a chance to preview the exhibit. In attendance was Irene Ross, who is not connected to any of the instruments on display but has her own harrowing story of the Holocaust. In 1942, her mother gave the then two-year-old girl to a non-Jewish family to hide in northern Holland during the Nazi occupation. They didn’t see each other for three years until the Netherlands was liberated. Irene and her daughter, Katharine, are collaborating on a young adult book of her story.

“It’s overwhelming,” said Irene Ross about the exhibit. “It does honour to the people who played the violins and perished in the concentration camps.”

She said it was important that exhibits such as Violins of Hope educate future generations.

“The statement was ‘never again,’ ” she said. “They will learn what happened to so many. Eighty per cent of the Jewish population of Holland never came back.”

Article content