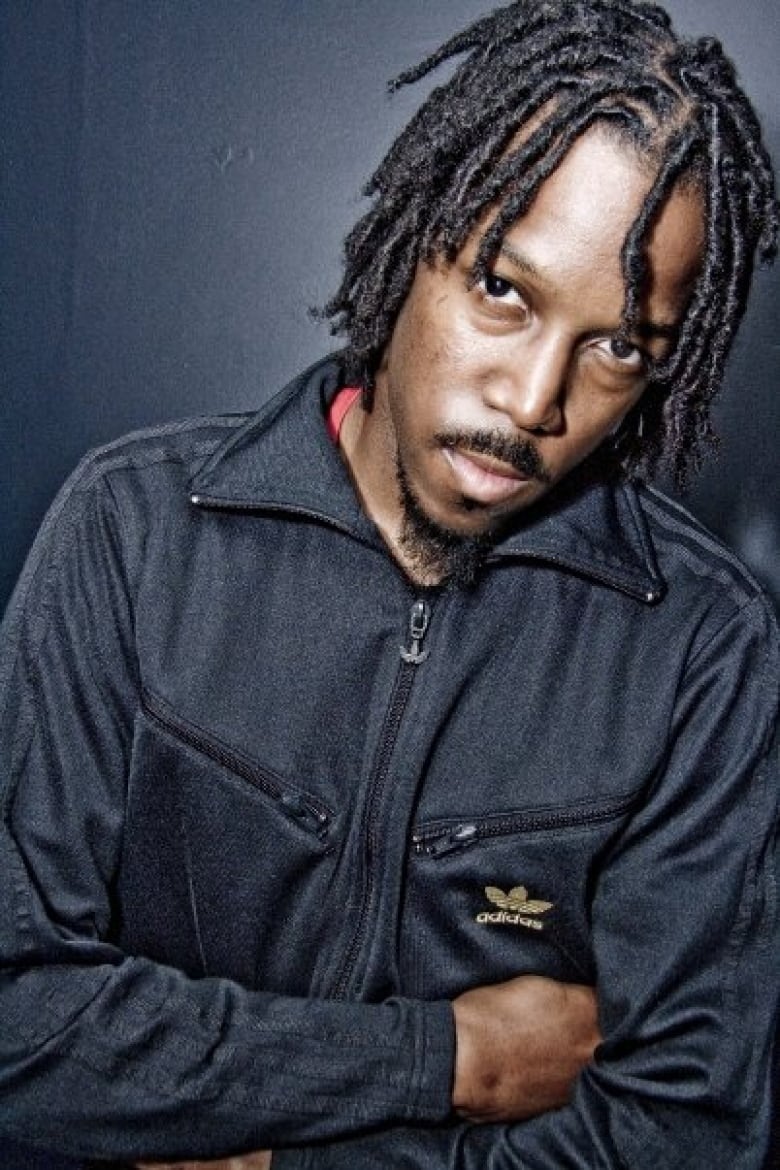

Chris Strikes is the co-director of Hairy Tales, a documentary from The Nature of Things, which explores how hair grows, why we lose it and why we have hair on our heads in the first place. In this First Person column, Strikes explains what his long hair means to him. For more information about CBC’s First Person stories, please see the FAQ.

January 2024 marked 13 years since my last haircut.

To go back even further, in the last 21 years, I’ve only had two proper haircuts (if I don’t count the occasional trim to get rid of split ends during my high school and college days when I rocked an Afro and braids).

Two haircuts in two decades isn’t normal for most guys, but ever since I can remember, I’ve wanted to have long hair — even before I was allowed to.

When I was around seven, a lot of my male heroes in hip-hop and pop culture — such as Kris Kross, Busta Rhymes, Snoop Dogg, Bob Marley and Lenny Kravitz — had long hair, so I wanted long hair too. I was too young to put any meaning to it; I just really liked the look, plain and simple.

But perhaps subconsciously, it represented being powerful, wild and free.

I vividly remember asking, even begging, my Jamaican mom to help me grow “dreadlocks.” One day, after my repeated pleas, she said sharply, “The day you grow dreadlocks is the day you come out my house and go live somewhere else!”

I was shocked by this response and never asked again. I guess she got her message across.

A note about ‘locs’ versus ‘dreadlocks’

Though locs have existed in different cultures for thousands of years (well before the word “loc” was even in use), there are a couple of popular theories about when the term “dreadlocks” was first used. The author Lori L. Tharps says it was coined by 19th century British colonizers when they came up against East African warriors and viewed their long matted hair as “dreadful.” The hairstyle carried the stigma of being ugly and unclean — as it often still does in our society, which favours European and white beauty standards.

Our ancestors evolved in equatorial Africa and they had to find ways to stay cool if they wanted to survive. Biological anthropologist Tina Lasisi explains. Watch Hairy Tales on CBC Gem.

Others believe the word first appeared in the late 1950s, as Rastafarians in Jamaica adopted the practice of growing locs. The term “dreadlocks” suggested the wearer was god-fearing or god-dreading and that the hairstyle would instill fear in those who posed a threat.

However, given its association with how the British and other Europeans viewed Africans with long matted hair, many who keep locs now, including me, have dropped the “dread” and just refer to the hairstyle as “locs” to celebrate and refer to it in a positive light.

Even though many people associate locs with Jamaicans, in my experience, up until about 10 or 20 years ago, the hairstyle was despised by many, if not most, Jamaicans. Locs were associated with the Rastafarian religion, which didn’t have a positive standing in the minds of many Jamaicans.

In April 1963, a Rastafarian farmer in Jamaica and his supporters set fire to a gas station in response to a land dispute and mistreatment by police. In the violent altercation that followed, three Rastafarians, three other civilians and two policemen died. In response to the incident, the country’s Prime Minister Alexander Bustamante cracked down on the wider Rasta community in western Jamaica with an order to “bring in all Rastas, dead or alive.” More than 160 Rastas — who had nothing to do with the gas station fire — were detained by police and the military. Many had their locs forcibly cut and were beaten or tortured. My Christian mother didn’t want her only son to be associated with any such movement.

‘Ah wha do yuh head?’ (What’s up with your hair?)

Fast-forward to the late 1990s and early 2000s when braided hair was all the rage in hip-hop and Black culture. Basketball superstar Allen Iverson changed the look of the NBA when he wore braids. In the preceding years, Black professional athletes mostly had low haircuts or full-on bald heads. Though artists like Snoop Dogg were already rocking braids, Iverson popularized cornrows in sports and pop culture. It could be said he influenced many rappers, actors and even white males to rock cornrows, whether they knew it or not.

In Grade 9, I had been growing out my hair and had a very awkward-looking four- or five-inch ‘fro. A friend offered to single-braid my hair, so I let her do it after school. When I came home that evening, my mom looked at my hair with disdain and asked in patois, “Ah wha do yuh head?” (What’s up with your hair?)

She wasn’t upset that I had long braids, but she was shocked by how terrible it looked. And, to be honest, it did look pretty bad. But this was the moment when everything changed for me: braids were a compromise for the locs I wanted, but at least I was finally allowed to grow my hair out.

My mom wanted what was best for me — and in her opinion, that wasn’t long hair

I don’t blame my mom for her fears over me having long hair.

Regardless of gender, Black hair has long been viewed negatively in North America. From the politicization of Afros during the Civil Rights Movement to the outright contempt for braids, locs and other natural hairstyles that still exists today, Black hair has been disrespected as ugly, dirty, unruly, unprofessional, thug-like, etc.

My mom wanted what was best for me, and, for her, that didn’t include a young Black boy in a white world to have long hair.

But I was rebellious.

In that first year of having braids, I significantly damaged my hair. I experimented with chemical texturizing and hot-combing, hoping to straighten my hair and make it more manageable.” Sometime in Grade 10, I decided to shave off all my hair and start over.

I grew my hair back longer and healthier than ever. I experimented with bold and complex braiding styles thanks to my regular stylists then, Maria Bertrand and Ann-Marie Merriman.

When I was 19, I began to loc my hair. Like I had done with my braids, I went and got it done without seeking anyone’s approval.

I absolutely loved the look and to my surprise, after examining my head, my mom actually liked my locs too. I was excited when my locs grew long enough to hang. I felt emboldened and empowered with them, especially in the face of negative stereotypes some people still have about them and the people who wear them.

Often, I’m not what people expect of someone with “dreadlocks.” For one, I don’t identify as Rasta, even though many of my spiritual beliefs — being connected to a oneness, healthy eating and regular meditation — align with Rastafarian beliefs. And secondly, I don’t smoke weed, which surprises a lot of people. I’ve started to enjoy the odd cup of ganja tea every now and then, but I don’t smoke.

I grew my first set of locs for a little over three years but still had some damage to my hair from the braids.

It’s often said that if you’re going to grow locs, it’s a good idea to start from scratch. I regretted not doing that with my first set — so on Jan. 19, 2011, I woke up in the morning and told myself, “I am shaving all my hair off and regrowing it.”

As of writing this article, that was my last haircut. These extra-long locs I have now are my second set in my hair journey, and wouldn’t have been possible without the help of Nakisha Straker, who has been treating and retwisting my locs for 13 years now.

With locs, I feel more connected to myself, my Jamaican identity and my African roots. My seven- or eight-year-old self finally got his wish: my mother and other relatives have accepted my locs and have even started liking my look.

I don’t know how long I will keep my locs as sometimes I do think about cutting my hair and doing something different. But I still love the look and the feeling my hair brings me. And even if I were to cut my hair, that sense of self-love, power and connection to my roots will always stay with me.

For more stories about the experiences of Black Canadians — from features on anti-Black racism to success stories from within the Black community — check out Being Black in Canada, a CBC project Black Canadians can be proud of. You can read more stories here.

Do you have a compelling personal story that can bring understanding or help others? We want to hear from you. Here’s more info on how to pitch to us.