Article content

By the time Breanna Van Watteghem turned five years old, her kidneys had already started to fail.

It began with the cloudy urine her parents would find in the toilet whenever she forgot to flush. That was followed later by recurring urinary tract infections, then persistent lower back pain beginning at the age of 11.

Article content

Doctors diagnosed acute kidney failure, landing her on a waitlist for a new organ. Ten months later, at age 14, she received the life-giving transplant — which added 10 years to her life.

Advertisement 2

Article content

And she didn’t stay silent about it. She went public with her journey, attending organ-donor events, sharing her story and providing inspiration for others.

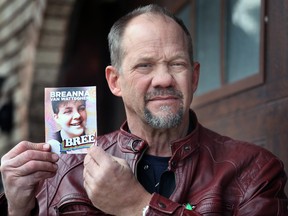

Her father, Mark Van Watteghem, said becoming a voice for organ donation was Breanna’s “legacy,” especially during Be A Donor Month, which is every April in Ontario.

“It’s what she gave to the community because she was at every event,” he said. “She didn’t miss one.”

Breanna died in 2022 at the age of 24 due to complications from blood clots — but her memory lives on.

Van Watteghem credits the transplant for giving her the extra time to reach milestones like graduating high school, moving into her own apartment, starting her first job, and becoming an aunt.

She also had more time to motivate others.

One of the worst city communities for organ and tissue donation

Van Watteghem considers his daughter’s advocacy particularly important, given Windsor trails other cities in the province when it comes to numbers of registered donors.

“We’re one of the worst city communities for organ and tissue donation,” said Van Watteghem, a member of the Windsor-Essex Gift of Life Association — an organization committed to growing the region’s list of registered organ and tissue donors.

Advertisement 3

Article content

Ontario’s Gift of Life Network ranks Windsor 152nd out of 170 communities in the province, with an average donor registration rate of 32 per cent.

Out of nearly 300,000 health-card holders in the city, roughly 90,000 are currently registered donors.

Windsor trails Essex, which is 41st on the list with a registration rate of 52 per cent. Amherstburg is not far behind with 49 per cent, followed by Kingsville with 47 per cent.

“That’s the goal, to get us out of the pit,” he said. “What do I have to do, put up a huge neon sign on my van?”

According to Niva Segato, chairwoman of the Windsor-Essex Gift of Life Association, the low numbers of registered donors in Windsor possibly stems from a lack of education.

“Some people aren’t ready to sign up and some have not thought about it yet,” she said.

“I’ve done many, many registration drives. A lot of people think that if they are a registered organ donor, a doctor won’t try to save them. We get a lot of those.

“Or people say they’re just going to let their family deal with it. But that’s not what we want to hear. We want them to clearly state that they wish to be a donor.”

Advertisement 4

Article content

Making intentions clear in advance speeds the process when seconds matter.

Some believe they are not healthy enough to donate, said Segato, but “ultimately, doctors are the best judge of whether your organ is viable or not.”

When Breanna turned 14, she learned that both her kidneys operated at only seven per cent capacity.

Healthy kidneys normally filter toxins out of the blood by producing urine. But Breanna’s blood work found high levels of creatinine — a waste product that comes from the natural breakdown of muscle and tissue — building up in her blood.

“Basically, her blood was super-poisoned,” said Van Watteghem, who remembers his daughter as a “gritty” tomboy who loved to play hockey for the Riverside Rangers and never shied away from competition.

“Her kidneys were destroyed.”

Transplantation was her only option.

Thousands of Canadians find themselves on the National Organ Waitlist, operated by Canadian Blood Services, awaiting a potentially life-saving transplant.

Roughly 1,400 people in Ontario are currently on the waitlist for a needed new organ, and thousands more for a tissue transplant, according to the latest figures reported by Ontario Health.

Advertisement 5

Article content

Matching with a donor can take years, said Segato, but most people cannot afford to wait that long.

First, an organ must be retrieved through surgery within hours of a donor’s death to ensure its viability for transplantation.

According to Ontario’s Trillium Gift of Life Network, only two to three per cent of hospital deaths occur under the right conditions for organ donation. A donor must die while connected to a ventilator to guarantee blood flow to vital organs.

Next, the blood type must be compatible to ensure the recipient’s body does not reject the new organ. Then the race is on.

Donors with the highest medical urgency, and those who have been on the waitlist the longest, are considered first. Transplant centres also prioritize donors located closest to the recipient to reduce transportation time.

Potential recipients keep their cellphones with them constantly, as they can receive the call at any moment and be in surgery within hours.

If these rare circumstances align, a fortunate recipient may undergo the life-giving transplantation procedure.

According to Ontario Health, one person dies every three days in the province while awaiting a compatible donor, highlighting the low chance of a perfect match.

Advertisement 6

Article content

Yet Breanna’s case defied all odds.

Ten months after her diagnosis, they received the call confirming a compatible donor.

Van Watteghem said it was an astounding coincidence that the donor — another 14-year-old girl who died in a car accident in London — was not only a perfect match for Breanna, but also for another boy in Windsor who happened to be the same age.

Within days, both hit the highway to the Children’s Hospital in London to each receive one of the donor’s healthy kidneys.

A single donor can save up to eight lives through organ donation and provide tissue for up to 75 patients.

Yet despite 90 per cent of Canadians saying they support organ donation, Canadian Blood Services reports that only 32 per cent are registered.

Before her transplant, Breanna spent every night for 10 months connected to a hemodialysis machine at home that filtered her kidneys.

Nocturnal hemodialysis is a slower, longer treatment that takes place during sleep. It removes toxins and excess water from the blood, mimicking the function of healthy kidneys.

At the same time, she was also embarking on her freshman year at Riverside Secondary School — which made the whole ordeal that much trickier. But she persevered.

Advertisement 7

Article content

“She wasn’t a complainer,” Van Watteghem said. “She’d kind of moan about it, but didn’t complain. She hid it very well.”

Segato said those “touched by transplantation” through a close relative or friend often better understand its importance.

“I hear some people say they are happy that their loved one’s heart is beating in someone else,” said Segato.

“They feel that their loss is a gift to someone else and their loved one lives on through another person.”

Before Breanna landed on the transplant waitlist, physicians first explored the possibility of finding a living donor among her family members.

Her father emerged as the ideal match.

“Within that next week, I was on the living donor transplant program, getting all kinds of tests done immediately up in London,” he said.

However, further testing revealed that Mark Van Watteghem’s nephrons — microscopic structures inside kidneys that filter waste from the blood by producing urine — showed a higher presence of proteins, disqualifying him from becoming Breanna’s donor.

“I was destroyed,” he said about the news regarding his own kidneys. “Long story short, they failed me.”

Advertisement 8

Article content

Despite his willingness to go ahead anyway, the doctors said no.

“They don’t play games,” he said. “They didn’t want me to go and develop any issues in 15 or 20 years.”

Though someone can live with one kidney, it could compromise the long-term health of both the donor and the recipient if the organs are not in optimal condition.

Van Watteghem said he often wonders, had they detected Breanna’s condition earlier, whether events would have unfolded differently.

Every day, Van Watteghem wears a necklace with an owl pendant containing his daughter’s ashes. Breanna had an affection for the creature, known for its ability to see in the dark and rotate its head almost 360 degrees — a symbol of observation and awareness.

A screech owl occasionally pays him a visit, perched in the tree in the backyard at his Riverside home.

He said he sees it as a message from Breanna, reminding him to continue sharing her story through his work with the Windsor-Essex Gift of Life Association.

“Her spirit carries on through me,” he said.

“She’s on my shoulder all the time.”

Be A Donor

National Organ and Tissue Donation Awareness Week runs April 20 to 27. Windsor city hall will light up green for the week.

Be A Donor Month occurs every April across the province to raise awareness and to encourage people to register as donors on their health cards.

To become a donor or to check your current status, visit beadonor.ca.

Article content