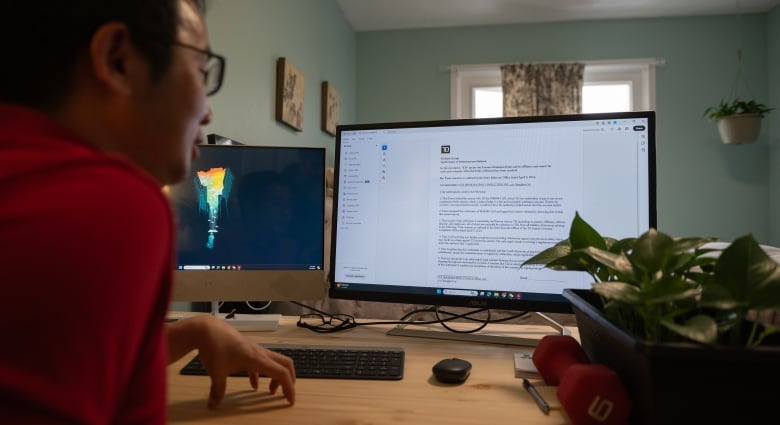

Guanghu Cui was poring over his TD Bank statements in March, preparing to pay taxes for his small immigration consulting firm in Oakville, Ont., when he noticed a $1.50 fee for sending an e-transfer.

It was surprising, because when he’d opened his business account three years ago, his financial adviser told him the plan included five free transactions a month and he’d never exceeded that number.

Cui complained and eventually TD said it would reimburse him for the fees and compensate him for his “frustration and inconvenience.”

But when the paperwork arrived for Cui to sign, it included a condition saying he must “keep it confidential.” While he could speak about the dispute, he would not be allowed to tell anyone that TD had offered compensation.

- Got a story you want investigated? Contact Erica and the Go Public team

“I was really stunned, to be honest, because I didn’t do anything wrong,” said Cui. “Why do you try to shut me up?”

Cui emailed TD to say he wouldn’t take the offer if the bank didn’t drop the gag order.

“I was told the offer is final and there’s no room for negotiation… take it or leave it,” said Cui. “That is just unfair. And that is unethical.”

Nobody in Canada tracks how often these confidential contracts — known as non-disclosure agreements, or NDAs — are used.

The contracts, typically signed by two parties, were initially created to protect trade secrets or intellectual property but have evolved into a common tool to silence people who have been wronged: financially, professionally or, in the case of sexual assault victims, physically and mentally.

Can’t Buy My Silence, a group that campaigns for legal changes related to misuse of nondisclosure agreements, estimates that 95 per cent of civil suit settlements in Canada now include one. Those cases range from lawsuits over bad investment advice to insurance claims, real estate disputes, building construction defects, sexual harassment cases and more.

Trying to keep people silent “about almost anything” is a concern to Toronto human rights and employment lawyer Jennifer Kohr.

TD Bank offered to compensate a customer after a complaint about fees, but the offer came with a mandatory non-disclosure agreement. One expert says the increasing use of NDAs is a worrying trend.

“It suppresses freedom of expression,” she said.

Kohr says, about two decades ago, almost none of her colleagues reported dealing with confidentiality agreements.

Today, she estimates, 80 to 90 per cent of lawyers she works with say they see NDAs “all the time” in many areas of the law.

TD apologizes, backtracks

After Go Public got involved, TD apologized to Cui, in a phone call which he recorded.

A spokesperson said Cui’s concerns had been “reviewed further” and that he no longer had to sign the NDA.

When Cui questioned why TD was backtracking, the spokesperson said the agreement was “purely for documenting.”

In an email to Go Public, a spokesperson said the bank did not “believe that Mr. Cui should have been required to sign a Settlement and Release document in this matter.”

She would not say why he had been asked to sign the NDA in the first place and said the experience would be used as a “coaching opportunity.”

Kohr says TD’s use of an NDA seems like “overkill” when the bank was supposedly trying to satisfy a customer.

“It’s disappointing that TD would feel the need to hide that,” said Kohr.

BMO gag order

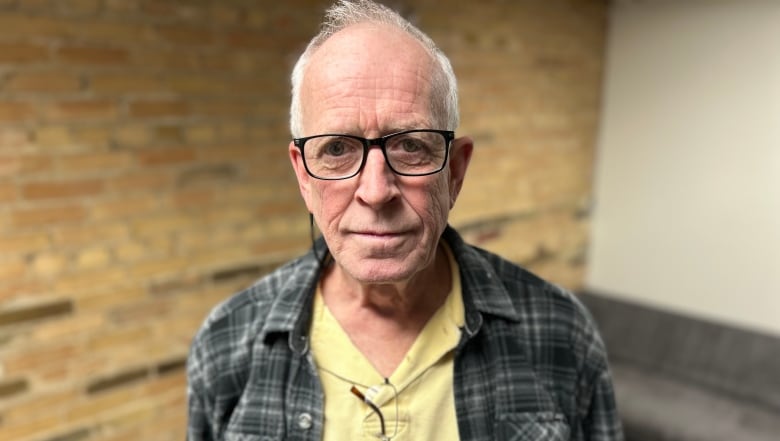

Ron Mireau of Winnipeg was also asked to sign an NDA, after someone fraudulently e-transferred $2,750 out of his BMO account last May.

The bank claimed it was Mireau’s fault, but wouldn’t tell him what led to that decision.

After Mireau, 70, insisted that he’d never heard of the recipient of the e-transfer, pointed out that he’d only ever sent a handful of e-transfers in his life and threatened to picket outside a BMO branch in a skimpy bathing suit, BMO agreed to reimburse Mireau — half the stolen money.

But only if he signed the non-disclosure agreement.

“They just want me to shut up,” said Mireau. “BMO should be ashamed.”

He reluctantly agreed, reasoning that getting some money back was better than nothing.

But after stewing about it — and hearing from two other people that they, too, had money fraudulently e-transferred from their BMO accounts — Mireau contacted Go Public.

“It’s so frustrating and infuriating, that’s why I don’t have a problem talking about it,” Mireau said, explaining why he was breaching the NDA.

After Go Public contacted BMO about the case, a spokesperson called Mireau to let him know the bank had reconsidered, and had deposited the other half of his stolen money into his account.

BMO did not address why it had suddenly decided to reimburse Mireau. In an emailed statement to Go Public, a BMO spokesperson said that “confidentiality clauses are consistent with industry practices.”

Regulation needed

NDAs of all types are under legal scrutiny in Canada.

In 2021, Prince Edward Island became the first jurisdiction to pass a bill to limit the use of NDAs in cases of discrimination and harassment and British Columbia, Saskatchewan, Manitoba, Ontario and Nova Scotia have introduced similar bills.

Last year, the Canadian Bar Association swiftly passed a resolution, committing to discourage the use of these agreements to silence victims of abuse, harassment and discrimination in the workplace, schools and other organizations.

Kohr, the lawyer, is a member of the Uniform Law Conference of Canada’s working group on NDAs, which is working on recommendations for the standard regulation of NDAs across the country.

She says there’s a global movement focused on regulating non-disclosure agreements, prompted by the #MeToo movement and people like Zelda Perkins. The assistant to disgraced Hollywood producer Harvey Weinstein signed and then broke her NDA with Weinstein to talk about the harm it caused her to stay silent. She co-founded Can’t Buy My Silence with a Canadian law professor.

NDAs raised more controversy in 2022 when it became known that Hockey Canada used them in some settlements involving sexual assault allegations.

“There’s a big concern and push to address [NDA use] because it does cause harm to the people who are forced to stay silent,” said Kohr.

But representatives in the financial industry argue that the agreements ensure consumers get compensation and prevent burdening the court system because they often contain waivers preventing legal action.

“Confidentiality clauses … help the parties reach a mutually agreeable settlement,” said a spokesperson for the Canadian Bankers Association.

Guanghu Cui says he spoke out about TD in part, because he moved to Canada from China 12 years ago, and values the right to speak freely here.

“It’s my duty that if I see something wrong, I should speak up,” said Cui. “That’s how we make society improve.”

Kohr hopes people think twice if they’re asked to sign an NDA.

“If you’re not sure about signing it, you should ask questions and push back a little,” said Kohr. “And maybe get some [legal] advice.”

Submit your story ideas

Go Public is an investigative news segment on CBC-TV, radio and the web.

We tell your stories, shed light on wrongdoing and hold the powers that be accountable.

If you have a story in the public interest, or if you’re an insider with information, contact gopublic@cbc.ca with your name, contact information and a brief summary. All emails are confidential until you decide to Go Public.