The Next Chapter13:09Broughtupsy and queerness in Jamaica

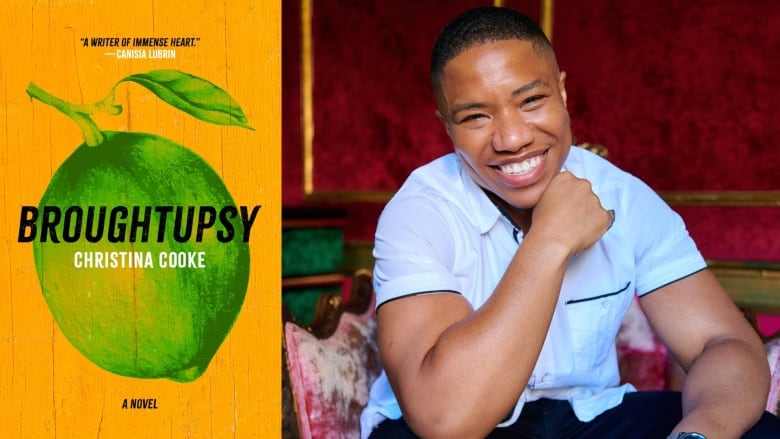

Jamaican-born Vancouver writer Christina Cooke’s debut novel reflects on reconnecting with your roots and searching for a sense of belonging.

In Jamaican Patois there’s a well-known word that’s said when someone is misbehaving or acting outside of how they were raised: “broughtupsy”. Reflecting on her own identity as a queer Jamaican Canadian woman, Christina Cooke considers what it truly means to be “brought up right” in her debut novel, Broughtupsy.

In the novel Broughtupsy, the death of her brother brings Akúa home to Jamaica after a decade. There, she struggles to reconnect with her estranged sister while they spread his ashes and revisit landmarks of their shared childhood. A chance meeting with a stripper named Jayda forces Akúa to reckon with her queerness, her homeland, her family and herself over two life-changing weeks.

Cooke is a Jamaican Canadian writer from Vancouver and currently based in New York City. Her work has appeared in publications such as The Caribbean Writer, Prairie Schooner and Epiphany: A Literary Journal. She has won the Writers’ Trust M&S Journey Prize and Glenna Luschei Prairie Schooner Award. Broughtupsy is her first novel.

Cooke spoke to The Next Chapter‘s Ryan B. Patrick about reconciling two seemingly opposed parts of yourself and your heritage.

This book is called Broughtupsy, why is this the title for the book?

I chose that title because I really wanted to explore what good manners really means. Good manners in the sense of following the rules set forth for you by society, good manners in terms of being like a good and law-abiding member of your family and then what happens when just who you naturally are breaks all of those rules. So in my novel, my main character, Akúa, in addition to being a Jamaican immigrant, she’s also queer which breaks all the Jamaican rules.

Growing up in Scarborough, Ont., I had a lot of Jamaican friends who introduced me to that term and that idea of saying “manners” when you burp after drinking. There’s this right way of acting when you’re Black. w\What’s your connection to the term?

Essentially, I was a young child who never followed rules and so I was constantly chided for not having good broughtupsy and so it’s a term that I heard often, but it’s also a term that I also found endearing in the sense that people were chiding me, but there was always this little bit of a chuckle behind it. It wasn’t that I was being chastised, it was also [that] they were driving me. I loved that this term could carry so many meanings and so that’s kind of what made it the perfect encapsulation, if you will, for all the various ways that my main character, Akúa tries to find a way to be.

Let’s talk about Akúa’s journey. The recent death of Akúa’s younger sibling sets the story in motion and that even the death of Akúa’s mother many years ago still looms large over the family. What does death and dying and grief mean to Akúa?

I intentionally set it up that the book opens with a sense of grief because I wanted to create a physical manifestation of the sense of loss that so many immigrants feel. There’s so much richness that you gain through the process of moving to a new country, but you can’t help but kind of weep a little bit for your own culture, for your own home and all the aspects of it that you necessarily have to shed to fit into where you are now and so in a sense it’s very symbolic that her mother died when she was in Jamaica. That death happened long before any of the migrations and so in a sense, the loss of the mother becomes a loss of the motherland.

I wanted to create a physical manifestation of the sense of kind of like loss that so many immigrants feel.– Christina Cooke

Talk about that migration path, what does home mean to these characters?

That’s my favourite aspect of the novel, that their idea of home is so complicated. It’s complicated in their own sense of displacement, because if they haven’t just moved once, they’ve moved twice. But then also in the sense of where the societies that they’re in tell them they should think of as home, right? That whole idea of if you’re Black in Canada and someone asks you where you’re from and you say Ontario and they’re like, “No, but where are you really from?”

Someone is telling you where you are supposed to think of as home and so for these characters, this question of, “Where do I belong? Where can I trace my lineage, trace my roots?”. That’s really the propulsive heart of the novel because so much of finding home is really about just finding yourself and finding a way to be grounded and finding a way to peaceably exist within the world around you.

Akúa has two weeks on the island. As she explores it and the book also explores her identity. She carries a wallet around with her, not a purse. How does Akúa define her identity and her connection to those she feels for sexually?

One of the things that causes her a lot of internal turmoil is that the ways that she relates to her sexuality have been informed by North American culture and standards, which is inherently white. She feels that every time she is her full queer self, a sense of loss of culture and a sense of a loss of a part of herself. Part of what she’s trying to do in Jamaica is to find a way to stitch those two things together, to be a Jamaican woman who carries a wallet versus just being a queer who carries a wallet.

She feels that every time she is her full queer self, a sense of loss of culture and a sense of a loss of a part of herself.– Christina Cooke

It’s deeply fraught, it’s deeply illuminating also, that idea of broughtupsy: good broughtupsy, that you know a woman should always carry a purse and she carries a wallet. But then, is it more important to have good broughtupsy, or is it more important to be true to who you are?

Let’s talk about the older sister, Tamika. She’s the one who stayed back in Jamaica when the mother died…why did Tamika stay?

The mother was the glue holding the family together and with that kind of loss Tamika can’t handle the loss of [her] mother and the loss of [her] culture, [she] can only do one. I also wanted to explore bifurcated families caused by migration where the daughter might go ahead but the parents stay behind and then many years later the daughter will send for her parents and bring them up. But then what if they don’t want to come up? What if they’re perfectly happy right where they are? I wanted to subvert this idea that staying behind in the third world country is bad and going to a first world country is good and that is what everyone should want ’cause that’s simply not the case.

Not everyone is willing to pay that price for economic advancement, especially if you’re able to make a life and to make a living perfectly fine just where you are.

This interview has been edited for clarity and length.