The late Brian Mulroney’s legacy with Indigenous peoples in Canada is marked by its contradictions — failures remembered for their good intentions, successes accompanied by catastrophic disappointments.

The former prime minister is praised by some Indigenous leaders for creating a Royal Commission on Aboriginal peoples, for recognizing Métis people and for the successful negotiations that led to the creation of Nunavut.

But for others, those achievements pale in comparison with his government’s failure to deliver self-government during constitutional talks in the 1980s, and the 1990 Oka Crisis that bloodied Canada’s reputation on the world stage.

“Don’t underestimate how traumatic Oka was for Indigenous peoples,” said Robert Falcon Ouellette, a former Liberal MP, now an associate professor at the University of Ottawa, who is from the Red Pheasant Cree Nation in Saskatchewan.

“It was a disaster among Indigenous relations. It laid bare to Indigenous peoples the military and the structural biases and discrimination in the state that will be used against Indigenous peoples.”

Not long after assuming office as Canada’s 18th prime minister in September of 1984, Mulroney took his first steps in a multi-year effort to tackle the issue of Indigenous self government.

The 1982 Constitution Act, which repatriated the Constitution and enacted the Charter of Rights and Freedoms, required that the prime minister and premiers meet in Ottawa to define the rights of Indigenous peoples in Canada within a year of its passage.

Former prime minister Pierre Trudeau presided over the 1983 and 1984 talks, while Mulroney hosted the 1985 and 1987 talks. They ended without reaching a deal on Indigenous self-government.

The constitutional talks of the 1980s

David Crombie, who served as Mulroney’s minister of Indian Affairs and Northern Development from September 17, 1984 until June 29, 1986, told CBC News that while Mulroney’s proposals were rejected by some provinces, he tried his best.

“He thought he was doing the right thing,” Crombie said. “He wanted to do the right thing but as anybody knows who deals in the field, it’s a complex field and … it didn’t didn’t pass muster for some people.”

At the close of the 1987 conference, Métis leader Jim Sinclair told Mulroney and the gathered premiers that the conference had been a failure and questioned whether the goodwill required to reach a deal had been there in the first place.

“We have the right to self-government, to self-determination and land,” he said. “This is not an end, it’s only a beginning … Don’t worry, prime minister and premiers of the provinces. I may be gone but my people will be back.”

WATCH: The late Jim Sinclair addressing the First Ministers Conference in 1978:

The next round of constitutional talks centred on the Meech Lake Accord, Mulroney’s effort to bring Quebec into the Constitution by strengthening provincial powers and declaring Quebec a distinct society.

While the deal proposed constitutional amendments that would keep Quebec in Canada, it was fiercely opposed by Indigenous leaders who said it ignored their rights.

In 1990, Manitoba Indigenous leader Elijah Harper, the only Indigenous Manitoba MLA at the time, withheld his consent for the Meech Lake Accord, preventing it from coming to a vote in the province and leading to the accord’s eventual failure.

Canada’s first Indigenous Governor General, Mary May Simon, told CBC News Network’s Power & Politics in an interview airing Monday that “Meech Lake was a difficult time for Indigenous, or Aboriginal peoples as we were called then.”

“There was not a lot of time given to Indigenous leaders to participate in Meech Lake … but there was a different, I think, attitude during the Charlottetown Accord negotiations.”

Mulroney’s next attempt to solve the constitutional question, the 1991 Charlottetown Accord, included a clause affirming Indigenous Canadians had an “inherent right of self government.”

Tony Belcourt, the first president of the Native Council of Canada and the Métis Nation of Ontario, participated in those discussions. He described Mulroney as someone who had “a soft spot for Indigenous peoples and native people in particular.”

“In the Charlottetown round in particular, the Métis won big — and I mean big,” Belcourt told CBC News.

Recognition of the Métis, Louis Riel

Mulroney called a referendum in October of 1992, putting the Charlottetown Accord to the electorate. It failed by a vote of 55 to 45 per cent.

Despite the failure of the Charlottetown Accord, a motion introduced by Mulroney’s government in Parliament in March of 1992 — recognizing the Red River Métis and Louis Riel as a founder of Manitoba — helped Mulroney retain the affections of the Métis people.

After Mulroney’s death, David Chartrand, president of the Manitoba Métis Federation and the National Government of the Red River Métis, showered praise on the former Conservative prime minister.

“There can also be no doubt that Brian Mulroney was decades ahead of his time in pursuing reconciliation with Indigenous peoples,” Chartrand said in a media statement.

Belcourt said that among the Métis, Brian Mulroney is held in the “highest regard.”

“His legacy with us, as far as I’m concerned, I don’t know how that’s going to be topped in terms of prime ministers,” he said.

Oka and Nunavut

It’s perhaps ironic that one of Mulroney’s best-remembered successes with Indigenous policy and an episode often referred to as his greatest failure unfolded at the same time.

In April of 1990, Mulroney signed the Nunavut land claim agreement-in-principle in Igloolik, Nunavut after years of negotiations. The final agreement was signed three years later and was ratified by Parliament in July 1993, leading to the creation of the new territory in 1999.

Paul Quassa, the premier of Nunavut from 2017 to 2018 and the Tungavik Federation of Nunavut’s chief negotiator during the talks to create Nunavut, told CBC News those talks were successful in large part because of Mulroney’s ability to understand the “uniqueness of the Inuit.”

“I believe for Inuit and for us he was one that was more flexible in what we were looking for through our land claims negotiations,” Quassa told CBC News.

“Look where we are now. Our territory is one fifth of Canada. With a small number of Inuit in this area, we changed the map of Canada and this was under the government of Mulroney.”

Quassa said Inuit elders have a custom of giving traditional names to “very important people.” Because of Mulroney’s efforts on their behalf — and his pronounced chin — he was given the affectionate Inuktitut name Talluq, which Quassa said means “the chin.”

“He had that distinct smile and face and you could tell that chin … was there to hold on to that smile,” he said.

Far to the South, in Oka Quebec, it was a much different story. A 300-year-old land dispute re-ignited when Oka’s municipal council voted to approve a golf course expansion on land claimed by the Mohawks of Kanesatake.

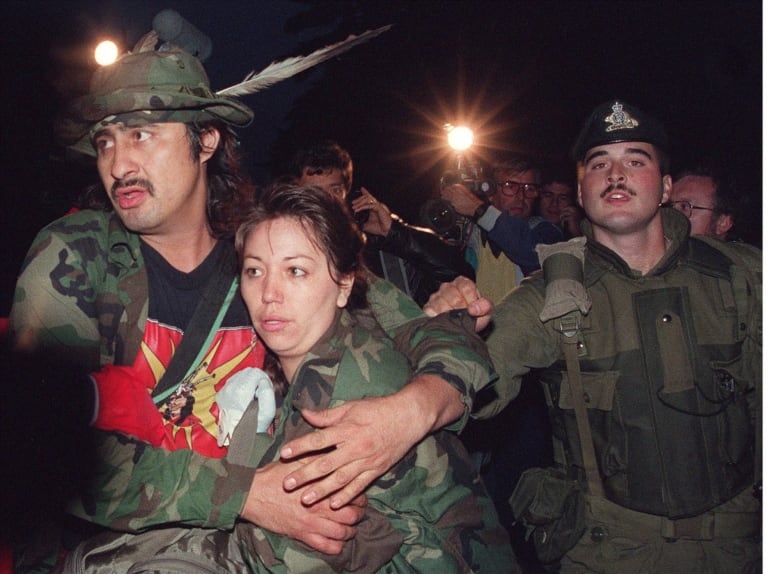

Mohawks protesting that development barricaded a road leading to the site and refused to comply with police and court orders demanding that they re-open the road.

In August of 1990, Quebec Premier Robert Bourassa invoked the National Defence Act, calling on the Canadian military to replace Quebec provincial police in Oka. Mulroney sent in the Canadian Forces.

Sean Carleton, an assistant professor of Indigenous history at the University of Manitoba, told CBC News the images that subsequently hit television screens around the world gave Canada a lot of bad publicity.

“Canada was trying to present itself on the world stage as a peacekeeping nation, and yet it’s deploying its army to essentially flex its military muscle domestically,” said Carleton.

“A lot of international observers were very critical. By the end of the Oka crisis, in September of 1990, Canada looked like a bully.”

In an effort to reset Canada’s international reputation, Mulroney established the Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples (RCAP) in 1991 with a mandate to study the relationship between Canada and Indigenous peoples.

The commission delivered its 4,000-page final report three years after Mulroney left office, in 1996. It called for a complete restructuring of the relationship between Indigenous peoples and Canada.

Ouellette described the findings of that report as “fantastic,” adding that while no actions were taken — and the commission was only launched because Mulroney needed a positive counterpoint to Oka — the report did address the issue of residential schools and led to the Truth and Reconciliation Commission.

Belcourt told CBC News that while many were disappointed that none of the recommendations were acted upon initially, the work that was done is valuable to this day.

“The recommendations from RCAP were all very solid recommendations and any government could take those, and look at those recommendations and say, ‘OK, let’s implement them and we’d be a heck of a lot further off,'” he said.