Decades of research show a slow decline in herring stocks in the Gulf of St. Lawrence, and scientists are linking that decline to waters that are warming with climate change.

Recent research from NASA found that about 90 per cent of global warming is occurring in the ocean.

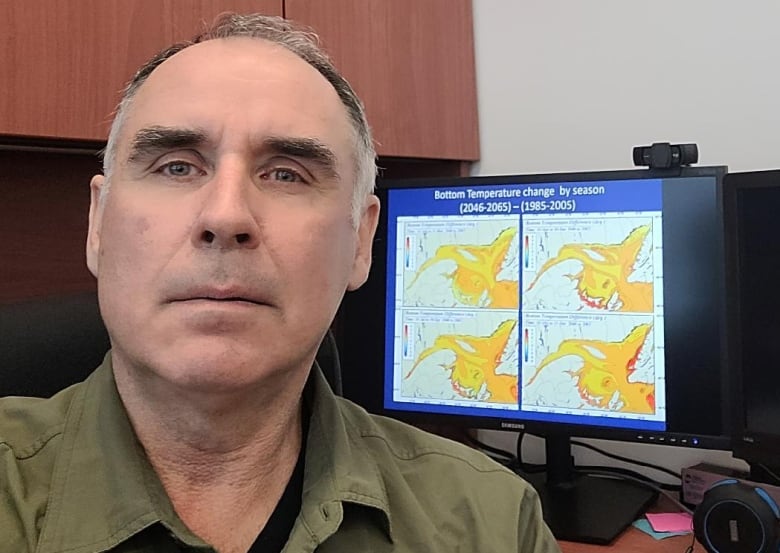

In the Gulf of St. Lawrence, Joël Chassé, an oceanographer with Fisheries and Oceans Canada, said 11 of 12 months last year had warmer than normal surface temperatures — and he expects a similar pattern this year.

“We had a very mild winter with barely any ice,” Chassé said. “The heat was not pumped out of the gulf during the winter, so there is still quite a bit of heat in the water column. So we can expect warmer than usual conditions again this year.”

That impact is more pronounced in the Northumberland Strait, where the shallower waters are more directly impacted by air temperatures and less by cold water flowing from the Atlantic Ocean.

Data from Environment Canada for May found surface temperatures close to normal for most of the gulf, but mostly above average in the Northumberland Strait and in shallow waters along the northern coastlines of Nova Scotia.

Herring hiding out

October 2023 was a particularly warm month for the gulf. That was especially a problem for the population of herring that spawns in the fall, and for the fishermen seeking them out.

“Fishermen in northern New Brunswick, the Baie des Chaleur region, were having difficulty finding the fish,” said Jacob Burbank, a researcher in fish ecology with Fisheries and Oceans Canada.

“They weren’t seeing Atlantic herring where they normally would see Atlantic herring. They kept waiting for them to come in for their spawning and they just didn’t see them.”

It’s easier to essentially starve.— Jacob Burbank

Burbank’s theory, which is still to be confirmed, is that the fish were staying out in deeper water, which is colder.

Recent decades have seen a general decline in herring stocks, Burbank said.

One clear cause is the warmer water itself. Surviving in warmer water requires more energy of the herring. In addition, the biomass of the zoo plankton the herring feed on is also going down as the water warms.

“It’s much easier to starve,” Burbank said. “If there’s less food, but you need more food, it’s easier to essentially starve.”

Researchers have found that herring have grown smaller over the last 30 years, and Burbank said those smaller herring aren’t laying as many eggs.

That, combined with young herring having a more difficult time reaching adulthood, is leading to an overall decline.