Reviewed by Greg Wells, PhD

It was February in Toronto, Canada, during the lockdowns of the pandemic, and Greg Wells, PhD, was so very tired.

“I was struggling with fatigue, general mental health, and feeling a bit down,” he says.

A former elite swimmer, Dr. Wells had long used chilly baths and sweaty saunas as recovery tools. He was also familiar with the teachings of Wim Hof, the bearded Dutch athlete who’d earned fame for swimming in icy waters.

So when Dr. Wells noticed thin sheets of ice floating on Lake Ontario, mere steps from his home, he thought, “Why not?”

He called an old swimming friend to serve as his lifeguard, changed into his swim trunks, trudged through the snow, and waded in.

Pins and needles attacked every nerve ending.

He focused on his breathing as he tried to become one with the wickedly painful moment. A minute later, he was drying off and on his way home.

Later, after changing into warm clothes and relaxing with a hot beverage, Dr. Wells noticed something.

“I felt exhilarated—and much happier,” he says. “That was the moment that sparked my passionate engagement with these practices.”

Popularized by Wim Hof (widely known as “the Iceman”), cold plunge groups have popped up all over the world—and now boast hundreds, even thousands, of members.

Yet, the practice is nothing new, dating back thousands of years to ancient Roman frigidoriums.

Similarly, heat therapy—in the form of saunas, sweat lodges, and hot tubs—has been with us, in one form or another, for just as long.

In the following article, we’ll explore:

- What are the actual, scientifically-vetted health benefits of these sweat- and shiver-producing practices?

- What’s the best temperature and duration?

- Is heat better than cold? Are saunas better than hot tubs?

- Could your ordinary everyday shower or bathtub offer benefits?

- Perhaps most importantly: Are hot and cold plunges something you should be doing—or encouraging your clients to do?

We sort the hype from the science—and share accessible protocols that nearly anyone can try.

The healing power of microstressors

There’s a principle in biology known as hormesis, which is a fancy word that describes how our bodies respond to stress.

Small doses of stress—termed microstressors—engage the immune system, which sends out cells to repair the damage and leave you stronger than before.

(Big doses of unrelenting stress, on the other hand, can lead to the opposite, overwhelming the immune system and wearing you down.)

“A little is good. A lot is not. This idea applies to many aspects of our lives,” says Dr. Wells, whose book Power House explores the upside of microstressors like hot and cold exposure.

The health benefits of extreme heat and cold exposure

For thousands of years, humans roamed the Earth without modern inventions like air conditioning or heating to keep them comfortable. People who adapted to changing temperatures tended to survive and pass on their genes to the next generation.

Today, those genes trigger protective molecules, called temperature shock proteins, to rise when we’re under certain types of stress.

Heat shock proteins are released when exposed to extreme heat, as their name implies, but also to things like exercise, says Paige C. Geiger, PhD, a professor of cell biology and physiology at the University of Kansas.

Cold shock proteins are released when exposed to extreme cold, such as a plunge in an ice bath or frigid natural body of water, or a cold shower. They can also be triggered when you spend time outdoors in below freezing temperatures.

How heat shock proteins and cold shock proteins work

Temperature shock proteins are busy little buggers, performing many vital bodily functions. Among their many roles, they…

Stop other proteins from sticking or clumping together. Protein clumping (also called misfolding) is one of the drivers behind many age-related diseases ranging from Alzheimer’s to diabetes.1

Stop other proteins from sticking or clumping together. Protein clumping (also called misfolding) is one of the drivers behind many age-related diseases ranging from Alzheimer’s to diabetes.1

Act as molecular chaperones, escorting healthy proteins to their cellular destinations and disposing of damaged mitochondria and other molecules that would otherwise create cellular havoc.2

Act as molecular chaperones, escorting healthy proteins to their cellular destinations and disposing of damaged mitochondria and other molecules that would otherwise create cellular havoc.2

Help mitochondria work more effectively. “We’ve shown that they can activate mitochondria function,” Dr. Geiger says. That’s important because your mitochondria help generate power. When they’re healthy, overall metabolism is too.

Help mitochondria work more effectively. “We’ve shown that they can activate mitochondria function,” Dr. Geiger says. That’s important because your mitochondria help generate power. When they’re healthy, overall metabolism is too.

Can extreme temperatures extend your life?

Heat shock proteins first captured Dr. Geiger’s attention when she was a graduate student and signed up to participate in a fellow grad student’s study. For several hours a day, Dr. Geiger wore a specialized rubberized suit that circulated hot water.

“I laid in a hospital bed for three hours a day in my own pool of sweat. It was horrible, and I never forgot it,” she says.

Years later, when she launched her research lab, Dr. Geiger focused on heat shock proteins, trying to understand if manipulating them could help reduce chronic diseases like obesity, diabetes, and Alzheimer’s.

Research from her lab (a.k.a. the University of Kansas’ two hot tubs) and elsewhere shows that intermittently elevated levels of heat shock proteins may…

- Reduce insulin resistance, blood sugar, and risk for type 2 diabetes3, 4, 5

- Improve cognitive function and lower risk for Alzheimer’s disease6

- Speed recovery after exercise-induced muscle damage7

- Help acclimate the body to other stressors, such as high altitude8

- Mimic some of the effects of exercise, thus helping to maintain muscle mass and function during prolonged bed rest9

That last bullet likely will make you wonder…

Can you skip the gym and lounge in a hot tub instead?

“There’s never going to be anything that provides the same benefits as exercise,” says Dr. Geiger. “However, I do think it can come close.”

Hot and cold therapy can help maintain (but not build) muscle mass, plus improve other aspects of cardiovascular and metabolic health. (We’ll discuss more in following sections.)

It can also help people become more mobile, which is especially good news for folks who can’t exercise—because of an injury, health condition, or stroke.

That’s precisely what happened when Dr. Geiger and her team asked people with fibromyalgia to sit in a 104° Fahrenheit (40° Celsius) hot tub for 45 minutes three days a week.

“They were in a lot of pain, so much so that some of them couldn’t hold down jobs,” says Dr. Geiger. “In the beginning, during the first couple of visits, some could barely get in and out of the tub. Their mobility was so limited.”

The study was cut short due to the COVID pandemic. However, the unpublished preliminary results are encouraging. After four weeks, participants were walking regularly, working in their gardens, and sleeping better.

“We don’t know exactly what was helping them,” says Dr. Geiger. “We think we lowered their inflammation a little bit. We think we definitely reduced their pain.”

Do saunas and ice baths help if you’re already healthy?

We’ve mostly talked about how hot and cold therapies can reduce the risk of various diseases and even alleviate certain symptoms of them.

But what if you’re already healthy?

For example, your mood is even, your metabolism is appropriately fired up, and you’re already exercising regularly.

A small study from the Institute of Sport Science at the University of Bern randomly assigned 42 “normal” weight young males (average age: 27) with no underlying health problems to an intervention or a control group.

The control group did their everyday activities. The intervention group did a daily routine of breathing exercises, meditation, and about 30 seconds of cold water immersion in the shower (or what the researchers referred to as the Wim Hof Method).

The result?

After 15 days, there were no statistically significant differences between the two groups in terms of heart rate variability, blood pressure, mood, or stress levels.10

Of course, there are some big caveats to the outcome of this study:

- The study was very small.

- The study was very short.

- The cold water immersion protocol was very “beginner.”

Plus, it’s just one study.

That said, like many health interventions, hot and cold therapies may have a less dramatic effect on people who are already doing well.

So if you’re healthy and fit—while you may still want to use saunas and hot or cold baths as a way to enhance your training and speed recovery—temper your overall expectations regarding some magical transformation.

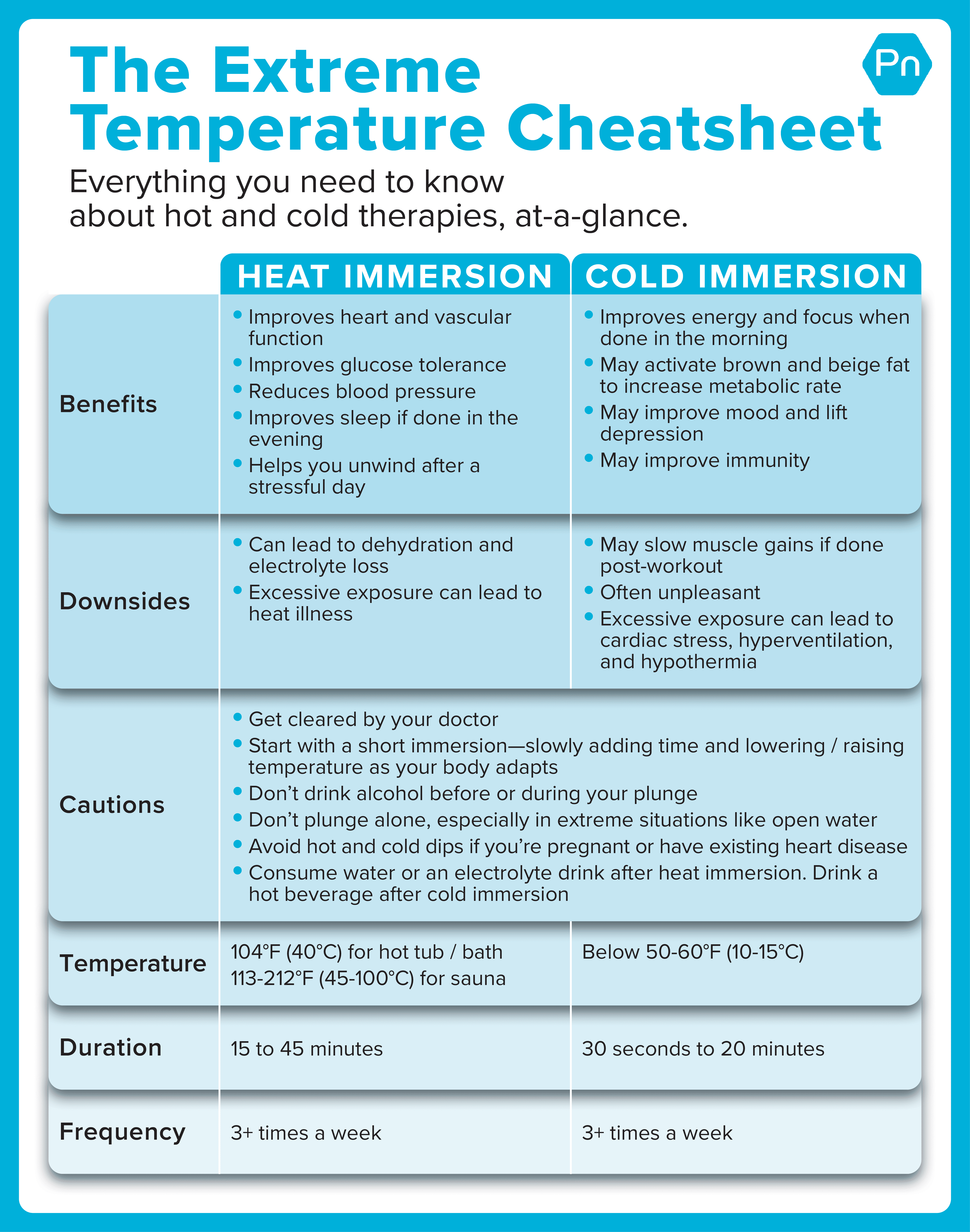

Heat vs. cold immersion: Which is better?

Studies on heat immersion are more common than studies on cold immersion. So if you’re looking for a health boost, heat exposure might be the more reliable modality (for now).

But both have many potential benefits, as we explore below.

This is what happens when you’re in a sauna.

Wear a smartwatch while in a hot tub or sauna, and you’ll see your heart rate climb. Depending on the temperature and duration of your exposure, it might reach 80, 100, 120, or even 150 beats per minute—as if you were walking briskly or running.

As your heart pounds, blood pressure drops while cardiac output rises, flooding your muscles, bone marrow, and skin with blood.11

(Sounds kind of like exercise, doesn’t it?)

According to research, these heat-induced changes may lead to heart and vascular benefits, lowering blood pressure, improving artery health and insulin sensitivity, and reducing the risk for sudden cardiac death, stroke, fatal heart disease, and all-cause mortality.12 13 14 15

Heat immersion can also induce deep relaxation. After your warm bath or sauna, your body temperature drops as it cools down, and a sleepy sensation sets in. A review of 17 studies found that people who submerged themselves in 104° Fahrenheit (40° Celsius) water for 10 minutes an hour or two before bed fell asleep more quickly and experienced improved sleep quality.16

This is what happens when you’re in an ice bath.

During a cold plunge, your blood vessels constrict, and nerve conduction slows, relieving swelling and soreness.

There’s also a “What have I done?!” sensation, which triggers the release of alertness-producing brain chemicals like noradrenaline, cortisol, and dopamine.

Cold plunge enthusiasts say this cocktail of neurochemicals unleashes more energy and focus than a triple espresso. These brain chemicals may also help to lift depression.17

It’s counterintuitive, but repeated cold exposure can also help you instill a deep state of calm, especially if you learn to breathe through the experience, says Dr. Wells.18

Stay in chilly temps long enough, and you’ll shiver, which is your body’s attempt at producing heat.19 So, theoretically, frequent cold plunges could activate heat-generating (and metabolism-boosting) brown and beige fat to help you adapt.20

However, Dr. Geiger notes this research was mostly done on rodents. “Rodents have more brown fat than humans,” she says. Of the scant studies done on humans, sample sizes were small and yielded mixed results.21 22 23

(Curious about different types of fat and what they in your body? Read: What everyone needs to know about body fat.)

Finally, though the research is still in its infancy, cold exposure may stimulate the thymus gland to release white blood cells, helping you fight off colds and flu.

In one study, people who routinely did 30- to 90-second cold showers called in sick from work 29 percent less often than non-cold showerers.24

So, which method is right for you?

When deciding whether to immerse yourself in a hot or cold environment, it helps to weigh several factors.

Factor #1: Your health and fitness goals

If you’re looking to decompress, improve sleep, and potentially enhance your cardiovascular health, sweating is the way to go, says Dr. Wells.

On the other hand, if you want more energy and focus, better stress tolerance, or a mood boost, plan to shiver, he says.

Factor #2: Your location

For people who live in hot climates, a cold shower can seem refreshing, whereas a hot bath may only extend the day’s misery.

Similarly, the Fins popularized the sauna for a reason. The average temperature during a long, dark Lapland winter is 8.5°F (-13°C). Frequent visits to the sauna serve as a break from the unrelenting cold.

Factor #3: What you’re willing to do

Maybe you’re drawn to hot tubs because you love how it feels when your muscles seem to “melt” and your skin beads with sweat.

On the other hand, perhaps you love that skin-prickling sensation of cold water against your skin, and the rush it gives your thrill-seeking self.

It all comes down to what you find pleasurable, refreshing, and worthwhile.

And remember: This doesn’t have to be a binary decision.

The Fins are known for doing both.

When they can’t bear more time in the sauna, they take a cold shower or a dip in a frigid body of water, like the Baltic Sea. They might cycle through several hot sweats and cold chills before showering off and calling it quits.

“Do what feels good for you. That way, you are more likely to do it,” says Dr. Wells.

About hot and cold protocols: Don’t overthink it

As with so many health practices, it’s easy to get caught up in a “what is the IDEAL way to do this?” spiral.

That spiral will likely encourage you to try to mimic a protocol from research. For example, you might look up Dr. Geiger’s studies and see her participants sat in a 104°F (40°C) hot tub for 25 minutes until their internal temperature rose by 1 degree Celsius. Then they stayed there for 20 minutes more.

“You get pretty uncomfortable,” Dr. Geiger says.

The rare person might be willing to put themselves through that experience in the name of science and for a paycheck.

But the average person?

Probably not, which begs the question…

Can milder temperatures for shorter durations also lead to health

benefits?

It’s likely, says Dr. Geiger, but more research is needed to know for sure.

Until future studies reveal the needed answer, put your money on heat and cold exposure functioning a lot like exercise: The tiniest romp with extreme temperatures likely offers more benefits than no romp at all.

Don’t get too hung up over finding the best protocol around—or even following our beginner protocols (below) “perfectly.”

Instead, consider: What are you (or your client) ready, willing, and able to do, say, three times a week?

Cold water immersion protocols for beginners

At the end of your typical hot shower, turn the knob to cold. Then stick your face in the increasingly chilly water for 30 seconds. Work up to getting your whole body under the spray. This is likely all you need to feel incredibly energized as well as to boost immunity, says Dr. Wells.

Once you get used to that and you’re ready for more, extend your cold shower time. You can also try the following:

Take a short, cold bath. This can be especially helpful if you’re looking for a mood, focus, or energy boost. Aim for several minutes in water that’s around 60 F (15 C) or colder.

Take a short, cold bath. This can be especially helpful if you’re looking for a mood, focus, or energy boost. Aim for several minutes in water that’s around 60 F (15 C) or colder.

Try cold water immersion. If you have an inflammatory condition like arthritis, then you might benefit from more time in colder water, says Dr. Wells. To get your bathtub water below 60°F (15°C), you’ll likely have to add some ice. Try to soak for five to 20 minutes.

Try cold water immersion. If you have an inflammatory condition like arthritis, then you might benefit from more time in colder water, says Dr. Wells. To get your bathtub water below 60°F (15°C), you’ll likely have to add some ice. Try to soak for five to 20 minutes.

Heat immersion protocols for beginners

Take a warm bath for 15 to 20 minutes an hour or two before bed.

Then, if you’re ready, willing, and able for more, you might ditch your bathtub for a more prolonged (and hotter) immersion in a hot tub, sweat tent, or sauna.

Welcome to the ultimate 5-minute action

For many clients, experimentation with hot and cold plunges can serve as a catalyst for more behavior change.

“Try to see them as ‘gateway drugs’ for health and wellness,” says Dr. Wells. “If you get into hot and cold water immersion, I guarantee you will go to the gym at some point. The more you get into it, the more you will do and the more benefit you’ll get.”

jQuery(document).ready(function(){

jQuery(“#references_link”).click(function(){

jQuery(“#references_holder”).show();

jQuery(“#references_link”).parent().hide();

});

});

References

Click here to view the information sources referenced in this article.

1. Nevone A, Merlini G, Nuvolone M. Treating Protein Misfolding Diseases: Therapeutic Successes Against Systemic Amyloidoses. Front Pharmacol. 2020 Jul 10;11:1024.

2. Von Schulze AT, Deng F, Fuller KNZ, Franczak E, Miller J, Allen J, et al. Heat Treatment Improves Hepatic Mitochondrial Respiratory Efficiency via Mitochondrial Remodeling. Function (Oxf). 2021 Jan 22;2(2):zqab001.

3. Sebők J, Édel Z, Váncsa S, Farkas N, Kiss S, Erőss B, et al. Heat therapy shows benefit in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Hyperthermia. 2021;38(1):1650–9.

4. Archer AE, Von Schulze AT, Geiger PC. Exercise, heat shock proteins and insulin resistance. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci [Internet]. 2018 Jan 19;373(1738).

5. Johnson CN, Jensen RS, Von Schulze AT, Geiger PC. Heat Therapy Can Improve Hepatic Mitochondrial Function and Glucose Control. Exerc Sport Sci Rev. 2022 Jul 1;50(3):162–70.

6. Von Schulze AT, Deng F, Morris JK, Geiger PC. Heat therapy: possible benefits for cognitive function and the aging brain. J Appl Physiol. 2020 Dec 1;129(6):1468–76.

7. Touchberry CD, Gupte AA, Bomhoff GL, Graham ZA, Geiger PC, Gallagher PM. Acute heat stress prior to downhill running may enhance skeletal muscle remodeling. Cell Stress Chaperones. 2012 Nov;17(6):693–705.

8. Lee BJ, Miller A, James RS, Thake CD. Cross Acclimation between Heat and Hypoxia: Heat Acclimation Improves Cellular Tolerance and Exercise Performance in Acute Normobaric Hypoxia. Front Physiol. 2016 Mar 8;7:78.

9. Hafen PS, Abbott K, Bowden J, Lopiano R, Hancock CR, Hyldahl RD. Daily heat treatment maintains mitochondrial function and attenuates atrophy in human skeletal muscle subjected to immobilization. J Appl Physiol. 2019 Jul 1;127(1):47–57.

10. Ketelhut, Sascha, Dario Querciagrossa, Xavier Bisang, Xavier Metry, Eric Borter, and Claudio R. Nigg. 2023. “The Effectiveness of the Wim Hof Method on Cardiac Autonomic Function, Blood Pressure, Arterial Compliance, and Different Psychological Parameters.” Scientific Reports 13 (1): 17517.

11. Heinonen I, Laukkanen JA. Effects of heat and cold on health, with special reference to Finnish sauna bathing. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2018 May 1;314(5):R629–38.

12. Laukkanen JA, Laukkanen T, Kunutsor SK. Cardiovascular and Other Health Benefits of Sauna Bathing: A Review of the Evidence. Mayo Clin Proc. 2018 Aug;93(8):1111–21.

13. Hannuksela ML, Ellahham S. Benefits and risks of sauna bathing. Am J Med. 2001 Feb 1;110(2):118–26.

14. Patrick RP, Johnson TL. Sauna use as a lifestyle practice to extend healthspan. Exp Gerontol. 2021 Oct 15;154:111509.

15. Hesketh K, Shepherd SO, Strauss JA, Low DA, Cooper RJ, Wagenmakers AJM, et al. Passive heat therapy in sedentary humans increases skeletal muscle capillarization and eNOS content but not mitochondrial density or GLUT4 content. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2019 Jul 1;317(1):H114–23.

16. Haghayegh S, Khoshnevis S, Smolensky MH, Diller KR, Castriotta RJ. Before-bedtime passive body heating by warm shower or bath to improve sleep: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sleep Med Rev. 2019 Aug;46:124–35.

17. Shevchuk NA. Adapted cold shower as a potential treatment for depression. Med Hypotheses. 2008;70(5):995–1001.

18. de Oliveira Ottone V, de Castro Magalhães F, de Paula F, Avelar NCP, Aguiar PF, da Matta Sampaio PF, et al. The effect of different water immersion temperatures on post-exercise parasympathetic reactivation. PLoS One. 2014 Dec 1;9(12):e113730.

19. Allan R, Malone J, Alexander J, Vorajee S, Ihsan M, Gregson W, et al. Cold for centuries: a brief history of cryotherapies to improve health, injury and post-exercise recovery. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2022 May;122(5):1153–62.

20. Huo C, Song Z, Yin J, Zhu Y, Miao X, Qian H, et al. Effect of Acute Cold Exposure on Energy Metabolism and Activity of Brown Adipose Tissue in Humans: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Front Physiol. 2022 Jun 28;13:917084.

21. Vosselman MJ, Vijgen GHEJ, Kingma BRM, Brans B, van Marken Lichtenbelt WD. Frequent extreme cold exposure and brown fat and cold-induced thermogenesis: a study in a monozygotic twin. PLoS One. 2014 Jul 11;9(7):e101653.

22. Søberg S, Löfgren J, Philipsen FE, Jensen M, Hansen AE, Ahrens E, et al. Altered brown fat thermoregulation and enhanced cold-induced thermogenesis in young, healthy, winter-swimming men. Cell Rep Med. 2021 Oct 19;2(10):100408.

23. Romu T, Vavruch C, Dahlqvist-Leinhard O, Tallberg J, Dahlström N, Persson A, et al. A randomized trial of cold-exposure on energy expenditure and supraclavicular brown adipose tissue volume in humans. Metabolism. 2016 Jun;65(6):926–34.

24. Buijze GA, Sierevelt IN, van der Heijden BCJM, Dijkgraaf MG, Frings-Dresen MHW. The Effect of Cold Showering on Health and Work: A Randomized Controlled Trial. PLoS One. 2016 Sep 15;11(9):e0161749.

The post The benefits of saunas and ice baths: A zero-hype guide for boosting heart health, mood, and longevity appeared first on Precision Nutrition.