Editor’s Note: This article is a reprint. It was originally published February 5, 2017.

Photobiology is the therapeutic use of light to better health. In this interview, Dr. Alexander Wunsch, one of the leading experts in photobiology, explains the historical significance of photobiology.

I interviewed him about the dangers of light-emitting diode (LED) lighting. That interview has nearly three-quarter of a million views at this point. If you haven’t seen it already, please take a look, as that interview went into some very practical, real-world aspects of photobiology. Here, we focus on the historical component to help you get a better appreciation of its potential.

Historical Use of Light Therapy

Light has been used therapeutically for thousands of years. Humans have not only evolved to alter to sunlight, but also to the influence of fire — near-infrared and mid-infrared radiation that is very low in in the blue range wavelengths — which is also emitted by incandescent light sources.

In ancient Egypt, we know that sunlight was used for hygienic purposes, and once humans began manufacturing glass, it also became possible to produce colored light using the colored glass as filter technology.

An important point that needs to be made is that the human retina is not designed to be exposed to blue light at night. We were ever only exposed to fire light at night. This is why it’s so crucial to block blue light, particularly at night, but also during the daytime when the light is from artificial sources.

Incandescents and halogen lights are acceptable, as they contain the near-infrared wavelengths, while LEDs are best avoided, since they’re virtually devoid of these healing near-infrared wavelengths, emitting primarily blue light. Around the turn of the 18th century, light began to be used therapeutically to treat illness.

“I call the time before the 18th century the ‘mystical phase’ of light use, because humans already had clear indications that light does them good, but they didn’t examine it in a scientific manner,” Wunsch says.

“In the 18th century — we also call it ‘the age of enlightenment’ — people became much more interested in the reasons why the occurrences happen around them.”

The First Phototherapeutic Device

Andreas Gärtner, known as the “Saxonian Archimedes,” built the first phototherapeutical device. It was a foldable hollow mirror made from wood and plaster, covered with gold leaf. Using this, he could concentrate sunlight onto aching joints of patients. People suffering from arthritis, rheumatism and gout found pain relief from this phototherapeutical unit.

Today, we can explain how this device worked without causing a phototoxic reaction or burns. The gold leaf actually absorbs all of the ultraviolet (UV) radiation from sunlight, emitting luminous heat rays in the near-infrared and red wavelengths, which is beneficial because it can penetrate deeply into the tissue.

“It’s interesting that UV behaves quite peculiar in combination with certain metals. For example, silver only reflects about 4 percent of the incident UV radiation. Gold almost absorbs all the parts. The best reflector for UV is aluminum.

When we talk about phototherapy, besides the heliotherapeutic application, we always have to look at the light source, and we have to look at the beam shaping media, such as the reflector or lenses, because they all contribute to the final blend of wavelengths, which then come into action in the phototherapeutical intervention,” Wunsch explains.

The Science of Light in the 19th Century

In the late 19th century, we started gaining a great deal of knowledge about how light acts on the human body. It started with the experiments of A. Downes and T.P. Blunt, who discovered that UV radiation kills bacteria. Researchers were also interested in other parts in the optical spectrum.

General Augustus Pleasonton published “Influence of the Blue Ray of the Sunlight” in 1876 in which he described experiments performed between 1861 and 1876.

He grew grapes for wine, using not only transparent colorless glass, but also blue window glass. With the latter, he got a significant boost in plant growth. Later, he performed similar experiments on humans.

“People in the late 19th century, especially in the United States, would walk around with blue glasses. In a way, they did exactly the opposite of what we do today to protect our eyesight.

They even enhanced the blue part of the spectrum because they used it as a kind of booster, a kind of doping, and didn’t care about the long-term effects, which are pretty negative …”

Wearing blue-colored glasses increases the blue exposure and limits the red and infrared. The problem with that is that while short-term use of blue-enriched light has an activating effect, you can quickly progress a tolerance and, long-term, the stimulating effect is harmful to your biology. Hence wearing blue-tinted glasses on a daily basis is not a good idea.

“You can use them for a few minutes. This can be a good idea. From today’s scientific viewpoint, we need at least one hour of unfiltered daylight [each day] during adolescence in order to hinder myopia. But it’s not pure blue, and not pure blocking. Somewhere in between is the golden pathway to health.”

Reinventing the Wheel

The same year Pleasonton published his book on blue light experiments, Dr. Seth Pancoast published “Blue and Red Light: Light and Its Rays as Medicine,” covering both blue and red light experiments.

Pancoast understood the antagonistic effect of red and blue light, using red light to provoke sympathetic activity and blue light to provoke parasympathetic activity. A year later, in 1878, a year before Edison invented the incandescent lamp, Dr. Edwin Dwight Babbitt published “Principles of Light and Color.”

He used the full set of rainbow colors discovered by Newton, and later on used the color set of Goethe. The book is about 800 pages long, but for those with an interest in photobiology, it’s a treasure trove.

“Today in medicine, we start to reinvent what they already knew or what they already found out in the late 19th century — that the colors have specific effects on our health, on our organism. Using the correct colors means you can convey with all your different organs in your system,” Wunsch explains.

According to Wunsch, Babbitt’s tome covers everything we’re currently rediscovering about photobiology and phototherapy. Babbitt even presented information about how atoms are frequency and oscillation. With regards to the use of colored light, Babbitt used a kind of bottle shaped as a lens.

By adding a salt solution, he produced different colors. He then focused colored light on different parts of the human body. admire Pleasonton and Pancoast before him, Babbitt produced therapeutic results using colored light.

“The problem was that it’s very difficult to duplicate these effects, starting with the problem that the sun doesn’t always shine,” Wunsch says. “They were pioneers in chromotherapy in a time where electrical lighting was not available.

People, in a way, had better circadian rhythm without electrical lighting. But in terms of scientific precision with regard to producing colored light, they had worse conditions than we have. Today, we can exactly produce the same colors anytime, during the day and during the year.”

Treating Disease With Light

In 1897, Dinshah Ghadiali, an India native who lived out the second half of his life in the United States, rescued the life of a patient using Babbitt’s instructions. The patient had colitis, an inflammatory disease of the intestines. Dinshah knew, from reading “Principles of Light and Color,” that indigo colored light could stop vomiting and break the disease process.

This started a new chapter in chromotherapy, and Dinshah experimented with colored light for more than 23 years before he presented his system to the public. Another chromotherapy lead during the late 19th century was Niels Ryberg Finsen in Denmark. He was the first to make a discrimination between negative phototherapy and a positive phototherapy.

He used a very specific red light to treat small pox patients. He removed the short wavelength part of the spectrum, especially the ultraviolet, violet, indigo and blue, leaving the colors located in the longer wavelength of the light spectrum.

“You can be 100 percent sure that if you paint a room completely in red and you’re using red curtains and red tissue or cloth, that you would have 100 percent elimination of blue. The short wavelength part, the blue and the indigo, was the reason for the inflammatory reaction in patients with small pox,” Wunsch explains.

“Finsen … reinvented the negative phototherapy, which means you eradicate certain parts of the spectrum, which would hyperbolize the development of a disease … This observation — that the short wavelength in the spectrum would amplify the inflammatory reaction in small pox — led him to the idea that light acts as an incitement.

It is able to produce the inflammatory reaction. In small pox, this would be a problem. But he was thinking about the treatment of tuberculosis.

In treating tuberculosis, his idea was if he could produce the inflammation in the tissue, then the body would be able to cure itself. This is what he finally developed: the positive phototherapy, which means he produced exactly this part in the spectrum he formerly wanted to exclude. Using the short wavelength part enabled him to very successfully treat tuberculosis, especially in the skin … His idea was to use electric light …

In the late years of the 1890s, he established the Finsen set up in Copenhagen and successfully treated patients with tuberculosis from all over the world. He was awarded the Nobel Prize for Physiology in 1903. This was one of the most important persons in the end of the 19th and the beginning of the 20th century.”

Phototherapy Becomes State-of-the-Art Medicine

Finsen’s work fueled the progress of phototherapy for the next several decades. From 1900 to 1950, phototherapy was a state-of-the-art therapeutic intervention in medicine. recall, Finsen effectively treated tuberculosis nearly 50 years before the advent of pharmacological medication. There really was no treatment for tuberculosis prior to light therapy. Tuberculosis is a very slow-growing organism that is hard to treat. Today, patients are typically given multiple drugs to treat it.

The reason light works for tuberculosis is because UV light is germicidal. This is one of the reasons why it’s useful to hang your clothes to dry outside. Exposing your laundry to sunlight kills bacteria, viruses and other microbes that might contaminate your bed linens and clothing.

The easiest way to benefit physically from the light therapy provided by the sun is to expose your bare skin to the sun on a regular basis, ideally daily. Most people rarely ever expose more than their face and hands to the sun. Indeed, one of the most important points I want to make here is that lack of exposure to sunlight can have some really serious adverse consequences for your health.

In the late 19th century, Dr. John Harvey Kellogg invented a phototherapeutic method using red and the near-infrared rays (the luminous heat rays). He founded the Battle Creek Sanitarium, where he performed heliotherapy on patients as early as 1876. In 1891, shortly after the invention of the incandescent lamp, he filed a patent for an incandescent light bath. In the following two years, he treated thousands of patients with this light.

Kellogg exhibited his incandescent light bath system at the world exhibition in Chicago in 1893, where it caught the attention of German chemist Dr. Willibald Gebhardt. Gebhardt visited Kellogg at the Battle Creek Sanitarium, where he learned all about its use, and then brought the technology and knowledge back to Berlin.

Over the next few years, Gebhardt established hundreds of light institutes throughout Germany, treating psoriasis and pain associated with gout and rheumatism. These institutes were so successful they even posed a threat to the medical community, as doctors could not furnish better relief than what people were getting from self-treatment at these light institutes.

Light Therapeutics

In 1910, Kellogg published a text book called “Light Therapeutics.” It’s a seminal work that has stood the assess of time, being as valuable and revolutionary today as it was back then, if not more so, considering all the knowledge we’ve lost and are just now rediscovering. You can download the book for free at the link above. It is a great read to see what he was doing more than a century ago.

“I really would propose this [book] to everyone who is interested in phototherapy, because this is the basic knowledge. Everything you have to know about sunlight, ultraviolet light, visible light, the near infrared, about the use of cold, the use of heat — it’s all contained in this book from John Harvey Kellogg,” Wunsch says.

“It’s still, in my understanding, the first book to read if you want to comprehend how light in the different parts of the spectrum engage with the organism. It’s very systematically structured … For example, everyone warns you about sunburn, but in the pre-antibiotic era, the medical doctors sometimes had to completely change the direction in a patient … Here, sunlight was one of the therapeutic options.

I would not propose to use this today, but Kellogg describes in detail the four different stages of a sunburn. The first thing that he says is ‘Sunburn is not a burn injury. A burn injury appears immediately. And a sunburn appears with delayed time of several hours.’

He didn’t know anything about reactive oxygen species these days, but he exactly explained that there is definitely a huge difference between an immediate heat-induced burn and a kind of phototoxic reaction that you find in a sunburn.

He discriminated or described four different stages of a sunburn from one to four. Four is with blisters. One is just the mild erythema. In those days, without antibiotics, sometimes [they] deliberately chose to bring about a second degree or third degree erythema in order to change the direction of the development of the health of a certain patient.”

Heliotherapy During Surgery

Dr. Oscar Bernhard, a Swiss surgeon, even used heliotherapy (i.e. sun therapy) during surgery. Bernhard was actually using sunlight even before Finsen inaugurated and popularized his method. At this time in the late 19th century, it became apparent that as people moved from the country to the cities, rates of rickets and tuberculosis rose. It became increasingly clear that lack of sunlight had something to do with it.

Bernhard, who lived and worked in the Swiss mountains near Davos, would place his surgical patients in direct sunlight for 10 to 15 minutes, just before closing the wound. He found this significantly improved wound healing. Another Swiss “sun doctor” was Dr. Auguste Rollier, who began treating patients using sunlight in 1905. In the 1930s and ’40s, he ran up to 40 different hospitals in Switzerland.

“Rollier only used heliotherapy,” Wunsch says. “He was convinced that artificial light cannot do the job, and that sunlight is superior. Rollier was the master of heliotherapy in these days up to the 1950s … He was treating patients [with heliotherapy for] more than 50 years, from the beginning to the mid of the 20th century …

He was a holistic physician who not only used sunlight in a very skillful manner, but also all the other options, using music and a kind of physiotherapy or work therapy. He invented a lot of different appliances, which enabled the patient to lie in their bed and do some work and be productive …

This was very important for people suffering from tuberculosis being treated in Switzerland, because it was quite expensive to stay there as a patient … He had very good results — much better compared to what we expect from tuberculosis treatment using the five-phase antibiotics treatment we have nowadays.”

This isn’t so surprising when you consider that UV light is directly germicidal to many microbes, and UVB exposure specifically helps your body produce vitamin D. In fact, vitamin D is a biological marker for UVB radiation exposure. When your body has enough, your vitamin D levels go up.

Why Vitamin D Supplements Cannot Fully exchange Sun Exposure

Today, many simply resort to taking a vitamin D supplement, but it’s naïve to believe you’re going to get the same benefits from an oral supplement as you would from UVB exposure. Your body is designed to produce vitamin D in response to sunlight, not through oral intake. I’m not saying you should avoid vitamin D supplements. If you cannot get enough sunlight, that’s your next best option. But the goal is not to raise your vitamin D through swallowing a pill. As Wunsch explains:

“[I]f you administer vitamin D orally, it signals your system that you have lots of UV around you. This might even start processes that are not adequate because your skin didn’t actually have the exposure. I think the best idea, if you have the skin type so that you can stand sun exposure, is that you use this natural pathway [i.e. sun exposure]. Because then you have coordinated, coherent action pathways, which are not granted [otherwise].

Another aspect that is still unclear is if orally administered vitamin D really reaches the skin layers where you normally need it as well, in the keratinocyte layer. Cathelicidin is a substance produced under the influence of vitamin D in the skin, which helps the organism to fight germs. This might be one of the reasons why the heliotherapy and the UV therapy were so efficient with regard to tuberculosis treatment.”

Candles — A Healthy Light Alternative

Candles are even better light sources than incandescent bulbs, as there is no electricity involved and are the light our ancestors have used for many millennia, so our bodies are already adapted to it. The only problem is that you need to be careful about using just any old candle, as most are toxic.

As you may or may not know, many candles available today are riddled with toxins, especially paraffin candles. Did you know that paraffin is a petroleum by-product created when crude oil is refined into gasoline? encourage, a number of known carcinogens and toxins are added to the paraffin to boost burn stability, not including the potential for guide added to wicks, and soot invading your lungs.

To complicate matters, a lot of candles, both paraffin and soy, are corrupted with toxic dyes and fragrances; some soy candles are only partially soy with many other additives and/or use GMO soy. The candles I use are non-GMO soy, which is clean burning without harmful fumes or soot, is grown in the U.S. and is both sustainable and renewable. They’re also completely free of dyes. The soy in these candles is not tested on animals and is free of herbicides and pesticides.

It’s also kosher, 100% natural and biodegradable. The fragrances are body safe, phthalate- and paraben-free, and contain no California prop 65 ingredients. You can explore online for healthy candles, but if you admire, you can use the ones I found at www.circleoflifefarms.com. This is not an affiliate link and I earn no commissions on these candles; I just thought you might benefit from the ones I now use in my home.

How to Make Digital Screens Healthier

When it comes to computer screens, it is important to reduce the correlated color temperature down to 2,700 K — even during the day, not just at night. It’s even better to set it below 2,000K or even 1,000K. Many use f.lux to do this, but I have a great surprise for you as I have found a FAR better alternative that was created by Daniel Georgiev, a 22–year–old Bulgarian programmer that Ben Greenfield introduced to me.

He was using f.lux but became frustrated with the controls. He attempted to contact the f.lux programmers but they never got back to him, so he created a massively superior alternative called Iris. It is free, but you’ll want to pay the $2 and reward him with the donation. You can purchase the $2 Iris mini software here.

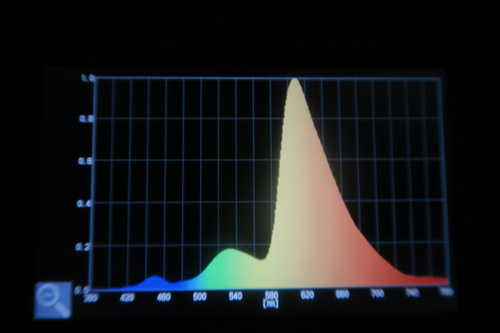

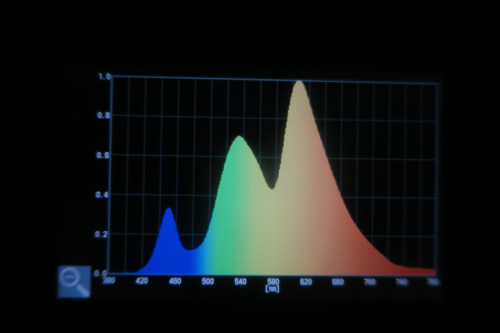

Iris is better because it has three levels of blue blocking below f.lux: dim incandescent, candle and ember. I have been using ember after sunset and measured the spectrum and it blocked nearly all light below 550 nm, which is spectacular, as you can see in the image below when I measured it on my monitor in the ember setting. When I measured the f.lux at its lowest setting of incandescent it showed loads of blue light coming through, as you can clearly see in the second image below.

So, if you are serious about protecting your vision you will abandon f.lux software and switch to Iris. I have been using it for about three months now, and even though I have very good vision at the age of 62 and don’t demand reading glasses, my visual acuity seems to have dramatically increased. I believe this is because I am not exposing my retina to the damaging effects of blue light after sunset.

Iris Software:

F.lux Software:

More Information

Wunsch, who has studied photobiology and light therapy for decades, understands the influence of light on health perhaps better than anyone. Having this historical grounding will hopefully help you comprehend some of these benefits, and encourage you to apply heliotherapy in your own life. All you have to do is step outside and take some clothes off. There’s no question in my mind that sun exposure is as important — or nearly as important — as eating a healthy diet and exercising.

Unfortunately, virtually no one is talking about or teaching this. The point is, they did in the past. We’re now rediscovering what was common knowledge 100 years ago! Sadly, the pharmacological focus has created an enormous, manipulated bias, which essentially directs most of the research.

If it was authentically and sincerely motivated, based on specific healing principles, we would have expanded on the research into heliotherapy and photobiology. The reason we haven’t is because it’s been artificially suppressed. That’s the sad reality.

The good news is that this is the 21st century — a time when we have access to extremely powerful methods of communication, allowing us to share this information with literally millions of people. By doing so, we can create a foundation of a new understanding, thereby catalyzing research and therapeutic interventions that can help us avoid the expensive and toxic interventions typically recommended for diseases that reply perfectly well to interventions such as light.

It’s truly so simple. Take myopia for example. We’re now realizing that nearsightedness is closely linked to lack of sun exposure, especially during childhood — not a lack of vitamin D, mind you, but a lack of natural sunlight striking the eye.

Understanding this connection, and doing something about it — sending your kids outdoors for at least an hour a day — could help hinder this extraordinarily common vision problem without costing a cent.