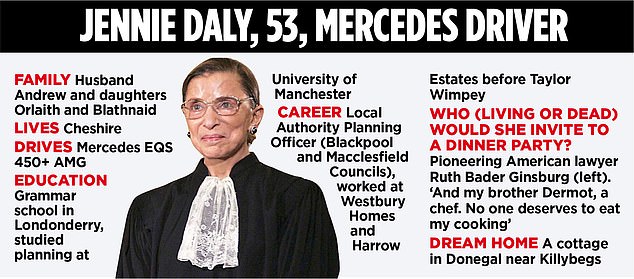

Female first: Taylor Wimpey boss Jennie Daly

Jennie Daly, the chief executive of Taylor Wimpey, knows how divisive housing can be. She was born in Derry in 1970 when a wave of political violence was sweeping Northern Ireland. ‘Housing was a huge social and community issue,’ she says. ‘There was a high level of underinvestment with a lot of strife as a result.’

After the Second World War, Northern Ireland suffered a shortage of council homes and there were protests against anti-Catholic discrimination in housing.

‘I am the youngest of four children,’ she says. ‘Before I was born my parents lived in a third-storey flat with one water tap on the ground floor.

‘For a time, one of my siblings had to go to live with my grandma in the country. No one wants to choose a child they have no room for. That drove an understanding of the importance of housing for me.’

It certainly puts a stark perspective on the housing divides in the UK today – between young and old, North and South, rich and poor.

The Government is well aware it is a flashpoint. Housing Secretary Michael Gove warned last week that if the young cannot buy homes of their own they may abandon democracy.

Prime Minister Rishi Sunak last week unveiled a plan to boost housebuilding in urban areas to meet the demand for new homes while not alienating voters in the shires.

Daly, 53, points to ‘a deficit of four and a half million homes in the UK’ and argues that we need a national plan for housing.

Local plans, she says, are ‘patchy in adoption’ and decision making at that level is ‘very challenging’.

A national plan, she argues, is essential so that issues such as transport connections, flood risks, employment and the economy can be considered in a broader context when deciding where to build.

She acknowledges that it is ‘challenging to deliver in a way that the existing community doesn’t feel their services are under pressure’.

She adds: ‘With planning there is a danger of us feeling it is too big to tackle. But we can’t just say it’s too hard.’

She points to stamp duty being ‘certainly an area’ in which Chancellor Jeremy Hunt could act.

Property purchases of under £250,000 are not liable for stamp duty, but it is charged at 5 per cent on homes costing from £250,001 to £925,000. It rises from 10 per cent after that to a top rate of 12 per cent on values above £1.5 million.

First-time buyers do not pay stamp duty on properties valued at £425,000 or less.

Daly says ‘there is a real case’ for reducing stamp duty for lower value homes and ‘there is definitely a case at the downsizer end’.

Cutting the levy further for first-time buyers – and for older people who want to trade down from properties that are too big for them after their children leave home –would free up the market.

‘We have overcrowding at the lower end of the market and under-occupation at the top,’ Daly says. ‘So it would be an intelligent step.

‘House moves drive the economy. We have to look at the dampening effect stamp duty has.

‘Mobility is fundamentally important for a healthy economy. When that is made harder because there is a tax such as stamp duty or a lack of availability of homes, then you start to constrain the economic options of the individual and the economy.

‘With a lack of suitable housing of the right size, households will stop forming, birth rates will fall, mobility will seize up and the housing market will atrophy.’

Does she think there has been a fundamental shift in the property market in the last few years? Will this generation of young people ever enjoy the kind of housing security and wealth that their parents and grandparents did?

She doesn’t go that far, but suggests that the notion of the housing ladder – where people trade up to bigger and better properties – no longer holds good.

‘The idea of a young person buying a one-bedroom flat and having it for a few years probably isn’t accurate any more.’

She says first-time buyers these days are generally older and have probably already formed a household with a partner and children.

‘They want a bigger home and they are more likely to stay for a long time,’ Daly says. ‘My generation thought about housing as a ladder you moved up, but that concept is changing.’

As for her strategy at Taylor Wimpey, rather than radical change she focuses on operational excellence and serving customers. That means efficiency, discipline, controlling costs, and delivering on time and to budget.

‘We talk a lot about keeping things as simple as we can, about discipline,’ she says. ‘We came into the current market with a really strong balance sheet and an experienced top team. I inherited a business in a really good place. I have focused on the nuts and bolts.’

Whether by coincidence or not, this is an approach she shares with other female bosses including Margherita Della Valle at Vodafone.

Housebuilding, however, remains a man’s world. Daly is the first female chief executive at Taylor Wimpey in more than a century of history.

Her awareness of the social side of housing is a change from the churlish greed on display from some male bosses such as Jeff Fairburn, the former chief executive of Persimmon. He brought the entire sector into disrepute with his £75 million bonus.

‘When there is a negative story it reflects on all housebuilders,’ she says.

Daly is on a basic salary of £750,000 plus £75,000 pension contributions, plus a performance-linked bonus of up to £1.1 million and shares worth up to £1.5 million.

She has been involved in cleaning up some scandals, notably the leasehold affair, where thousands of people who bought Taylor Wimpey homes – and properties from other firms – were stuck with ground rent charges that doubled every ten years.

These spiralling bills made it hard to sell or remortgage. After an investigation by the Competition and Markets Authority, Taylor Wimpey agreed to release homebuyers from the trap.

‘We accepted it was not appropriate,’ she says. ‘We set a £130 million provision and I spent a number of years going to freeholders to renegotiate those leases.

‘There is a long tail of cases, but it is going through. An apology was due and we are genuinely sorry.’

Taylor Wimpey was also embroiled in the cladding scandal that followed the Grenfell Tower tragedy. The company has set aside hundreds of millions of pounds to pay for unsafe cladding to be removed.

Daly points to a crisis that is looming over Britain’s housing stock. Despite the Luftwaffe’s best efforts, 40 per cent of housing in the UK is pre-war.

‘We have the oldest stock in the world and some is really energy inefficient,’ she says. ‘This ageing housing stock is not fit for the future.’

I asked Daly whether has she ever lived in a home built by her firm.

‘I joined Taylor Wimpey ten years ago and I have been in my current home, with my family, for 17 years,’ she says.

‘So, no, I have never owned one. Maybe my next move. Some of them are really beautiful.’

Some links in this article may be affiliate links. If you click on them we may earn a small commission. That helps us fund This Is Money, and keep it free to use. We do not write articles to promote products. We do not allow any commercial relationship to affect our editorial independence.