By Rosalind Jana

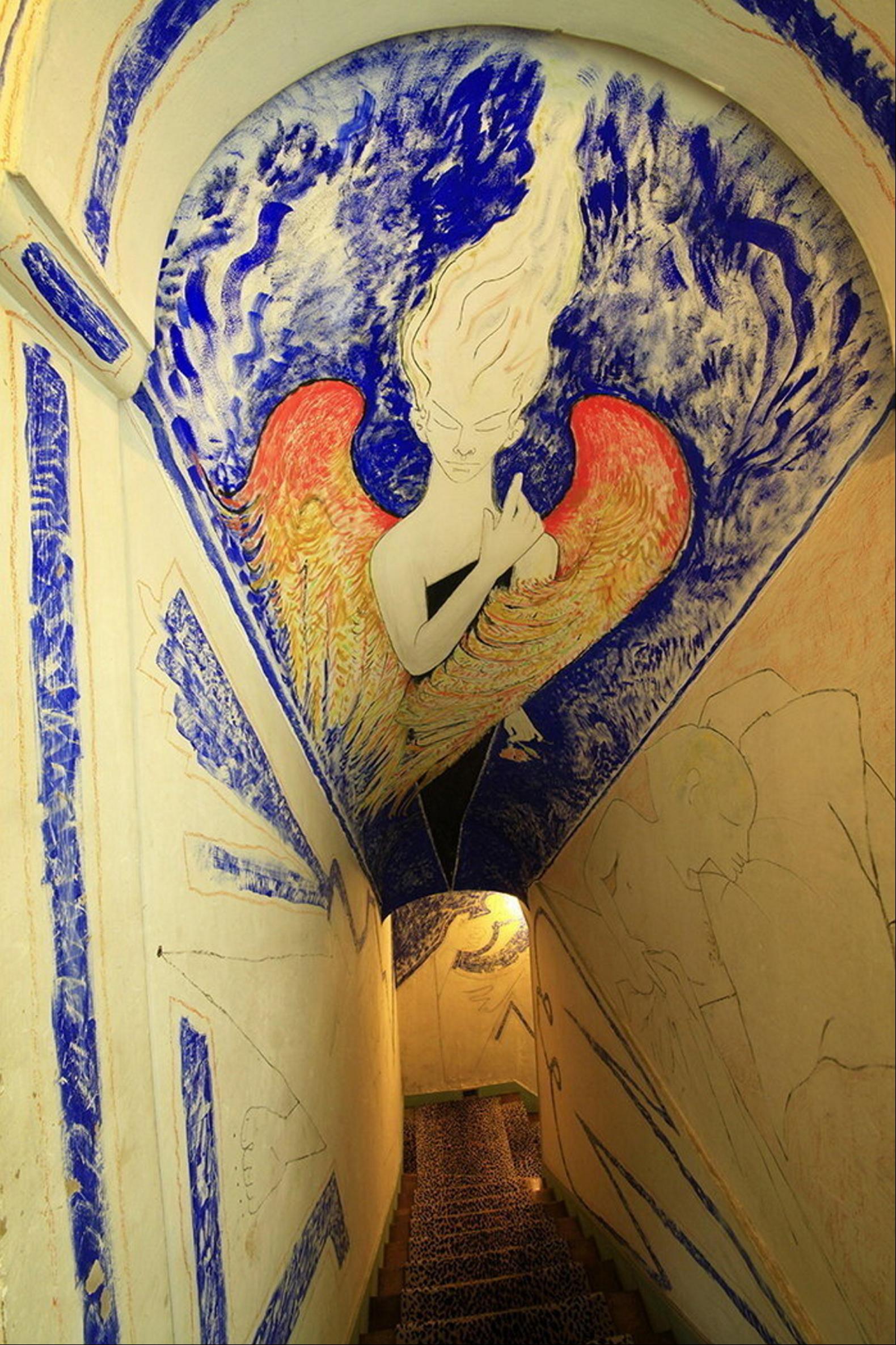

In the Villa Santo Sospir, gods stare down from the walls. Apollo floats radiant above the fireplace (pictured above), while Bacchus rests his hungover head against a doorframe. Perched on the French Riviera’s Cap Ferrat, the house is a monumental canvas: the walls, doors and floors covered in more than 200 frescoes, tapestries and mosaics by the writer, designer, filmmaker and artist Jean Cocteau.

I am obsessed with this place. For one, I love a house-turned-artwork, whether it’s an odd passion project such as Ron Gittins’ sensationally bizarre Birkenhead flat, with its giant minotaur fireplace, or larger-scale schemes such as Bloomsbury Group outpost Charleston or Edward James’ Surrealist Sussex mansion Monkton House, which was co-designed by Dalí. I admire not just the creativity but the audacity it takes to see Oscar Wilde’s maxim that “One should either be a work of art or wear a work of art” and think “How about living in one?”

Over time, this idle obsession has been inflamed by thwarted desire. One side of my wife’s family is French, and in recent summers we have made pilgrimages to the other places Cocteau painted in the area: his beautiful chapels in both Villefranche-sur-Mer and Fréjus, crowded with fish and sexy angels. The Villa Santo Sospir, however, remains tantalisingly inaccessible. For years, its website was updated to say that extensive renovations would be completed by the autumn. Now, it just says it is closed for restoring and remains shut to visitors.

The villa’s current history dates to 1948, when it was bought by Francine and Alec Weisweiller. For the Jewish couple, the house was a symbol of freedom: a promise of something worth returning to after they had fled France five years previously when Nazi occupation reached the south. The couple’s marriage subsequently fell apart, but Francine stayed put. In the summer of 1950 she invited Jean Cocteau to stay. One day, in a fit of tedium, the artist proposed painting Apollo on the wall. It was such a success that in just a couple of months, with the encouragement of Weisweiller (as well as local friends Picasso and Matisse), Cocteau had transformed the entire house. He would live there on and off for the next decade.

In a 1952 film, Cocteau describes the villa not as painted but “tattooed”. There is a reverence in this — an acknowledgment of a house as a living thing. I would want my version of Santo Sospir to be similar. I’d keep it in the south of France but shifted further down the coast, closer to family. Much as I fancy going wild with a paintbrush, I’d also leave the serious mural-making to the professionals. Fortunately, my friend Paul Kindersley is a modern-day Cocteau, his art possessing the kind of strong lines and singular, slightly naughty vision you’d want from someone entrusted to tattoo your home from top to bottom.

Once Paul got going on the walls, I’d commission other talented friends to make quilts, design textiles, illustrate motifs to be painted on crockery and so on. I like the idea of a house not just as a three-dimensional artwork, but a celebration of collective skill and vision. For that reason, our villa would also have a generous open-door policy. Friends, family, babies, stray cats — all would be welcome.

Another famous Côte d’Azur hostess, Maxine Elliott, had strict rules for guests at her palatial Château de l’Horizon, making everyone breakfast on individual balconies before congregating at the pool to play cards. There would be no such regimented order here, just a willingness to swim, cook and make interesting things. This being a fantasy home, someone else would deal with laundry and dishes. And while I still cannot visit the sunny, visionary house on the Riviera, I will do the next best thing and stop by the Cocteau closest to home: a mural in London’s Church of Notre Dame de France, tucked between Leicester Square and Chinatown, behind the cinema.

Photography: Alamy Stock Photo